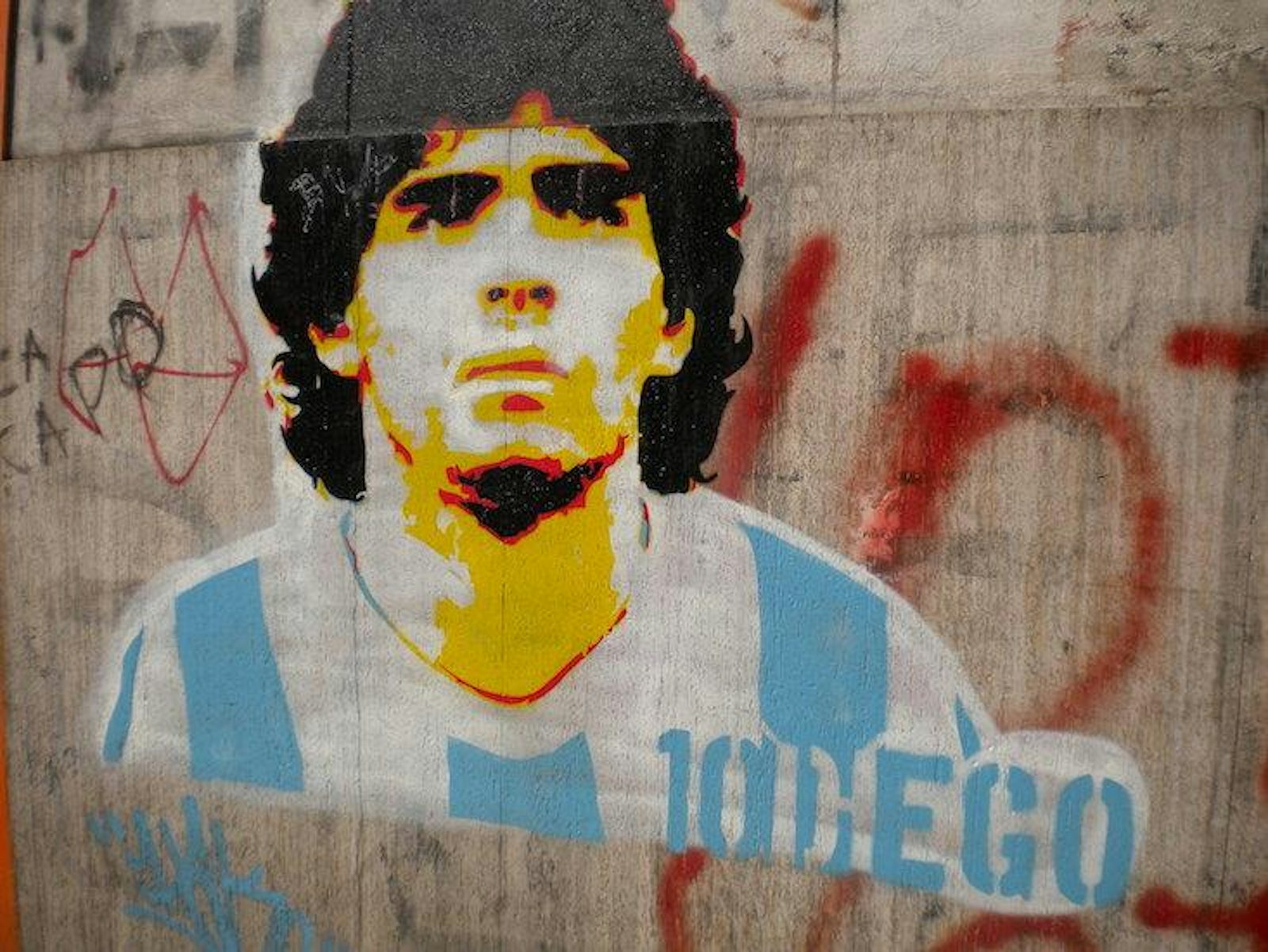

There is a church in Argentina called Iglesia Maradona. In this church, God is football—soccer—and its prophet is the renowned player Diego Armando Maradona. Founded in 1998, the year after the star’s retirement, the Church of Iglesia Maradona now has some 120,000 members worldwide, who bear its insignia D10S—a portmanteau of Dios, the Spanish word for God, and Maradona’s shirt number, 10. Members congregate in sports bars; transubstantiation occurs not to wine and wafer, but to beer and pizza. They even have their own version of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Diego, who art on the pitches, hallowed be thy left hand,” alluding to Maradona’s controversial “hand of God” goal in the 1986 World Cup.

It all sounds a bit absurd, but at least some of the church’s founders and followers appear to be serious. Co-founder Hernán Amez told The Argentina Independent in 2008, “It’s not just a bit of fun—it’s a religion. Religion is about feelings, and we feel football.” He is right, psychologically speaking. The power of religion, sociologist Émile Durkheim wrote, stems from its ability to unite two of our deepest yearnings—the universality of God and the cultural specificity of a clan—through totems and rituals. The specific beliefs of a religion do not matter so much as its ability to meet these emotional and social needs. In other words: deed then creed. Given this, Iglesia Maradona doesn’t seem so strange. After all, 90 percent of Argentinians declare allegiance to a soccer team. In many ways, the devotion to soccer in Argentina resembled a religion already.

While it may be common to think that ancient sporting rituals were performed in the service of religion, this modern example, and others, suggest it can just as easily go the other way: Religion adapts itself to sport. Take the United States, where football (American football) and Christianity are closely linked. Football counts 63 percent of Americans as fans, more than any other sport in the country—and 33 percent of them believe God intervenes in football games. As Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote in 2014, “The relationship between sports and religion in America has always been close, and it has often been awkward.”

Some might argue that this awkward closeness can be seen in the development of megachurches, defined as churches that have 2,000 or more in weekend attendance—they’re often modeled after sports stadiums. Crenshaw Christian Center, perhaps the largest such structure in the U.S., can pack 10,400 churchgoers into its 360-degree stadium seating. Critics of megachurches argue that their large size discourages nuanced discussions of social justice issues and the formation of intimate communities. What they do encourage, though, is group-feel. Sociologist Katie Corcoran has likened sitting in megachurch to standing in the crush of a packed stadium: Both allow the self to melt away.

“What has Jesus done that Maradona hasn’t?”

Recognizing this potential for self-transcendence, megachurches are now seeking to wield sports’ power for their own ends. In 2005, theologian Matthew Brian White examined the 100 largest megachurches to see how they used sports to win over followers, a practice known as “sports evangelism.” In addition to distributing pamphlets and videos at major sporting events, megachurches have created their own sports associations, such as Upward Basketball, which integrates religious practices into pre-game rituals and play.

“In a gym full of parents, uncles, aunts and grandparents, while the kids are off talking strategy, the adults are hearing about how to know Jesus,” White reports. “If we are to reach this type of world, we must use every tool at our disposal to capture the imagination of this leisure-oriented, unseeded and sports crazy culture,” writes John Garner, author of Recreation & Sports Ministry.

Iglesia Maradona, though, seems to have streamlined this formula: Forget the religious doctrines and sketchy historical figures—just worship the greatest sport and its greatest player. As Anthony Bale, a 23-year-old Scot who attended the Maradona Christmas celebration in 2008, at an Italian restaurant in the Argentinian city of Rosario, said: “What has Jesus done that Maradona hasn’t? They have both performed miracles. [It’s] just that Maradona’s are actually on record.”

Susie Neilson is an editorial fellow at Nautilus.

The lead photograph is courtesy of Cadaverexquisito via Wikicommons.