Most humans can be placed into three major categories of tasters—nontasters, tasters, and supertasters, roughly in the ratio of 25 percent: 50 percent: 25 percent. There is also a small percentage (less than 1 percent) of humanity categorized in a super-supertaster category. Supertasters are mostly women, and people of European ancestry are usually not supertasters. So what exactly is a supertaster? You might think that a supertaster would have a lot of fun eating and drinking, but it’s more like the opposite. Because supertasters experience tastes more intensely than nontasters and tasters, the effects of different tastes detected by tongues of supertasters are amplified relative to the nontasters and tasters. Super-supertasters have it even worse than supertasters. Taste is a good case of “more is not better.”

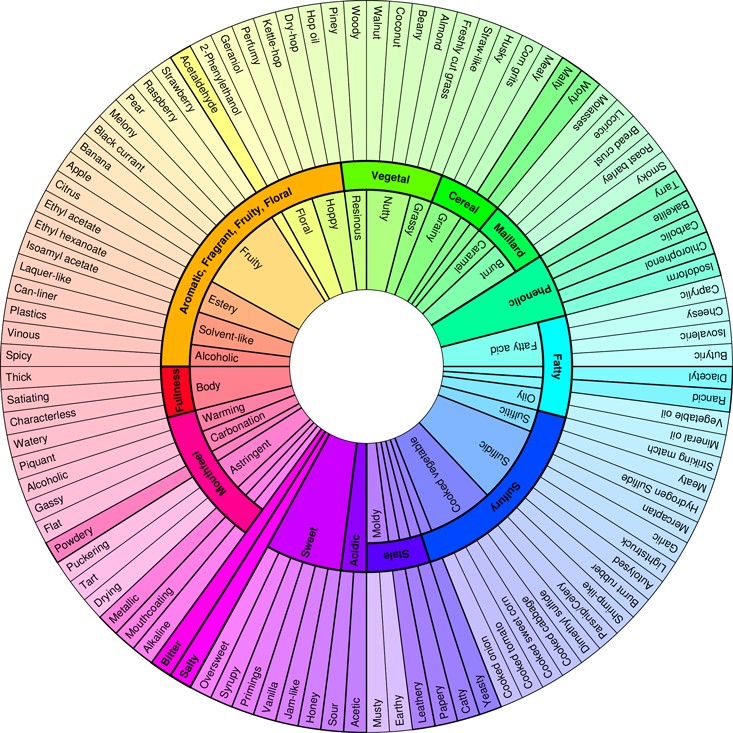

The best way to describe the differences between the categories of tasting is to take one of my favorite beverages to taste—beer—and explain how each of the categories of tasting will respond to this beverage. The Master Brewers Association of the Americas recommend what is called the American Society of Brewing Chemists flavor wheel to help its members assess the taste of their brews. The flavor wheel was created by a coauthor of Sensory Evaluation Techniques, first published in the 1970s and now in its fifth edition. Morten Meilgaard, a professor of the senses and how to measure them, created the taste wheel to lend a more quantitative aspect to beer tasting.

The taste wheel is quite complex and has gone through many iterations since Meilgaard created it, but it does focus on the complexities of the perception of beer. Examples of the more than 100 possible categories of taste include grapefruit, caramel, farmyard, funky, burnt tire, and baby sick/diapers (which I hope never to taste). It is safe to say that these tastes are the result of many factors, but they all emanate from the very simple contents of beer. In fact, to protect the simple contents of beer, in 1516 Germans created the Bavarian Beer Purity Law, or Reinheitsgebot. The purity law forbids any beverage labeled “beer” to be made with anything but hops, water, and barley. Although yeast is needed in brewing, it is a microbe, and was obviously not recognized as an ingredient 500 years ago. So, the modern concept of taste in most classical beers comes from only four ingredients. The most interesting aspect of the taste of beer, at least to me, comes from the hops and the sugars in the brew, and of course the alcohol that is the product of fermentation implemented by yeast on the sugars from grain.

Although beer is probably several millennia old, hops have been a part of brewing beer for a little more than a millennium. Its widespread use began in the last 800 years in Germany and was cemented in brewing technology with the invention of India pale ale (IPA) in the early to mid 19th century. With the modern advent of microbreweries and the development of custom-made hoppy beers such as the many IPAs that are on the market, this beverage becomes one that has a wide range of bitterness. It might be surprising to note that hops were first used as a preservative in beers. The bitter taste from hops is an afterthought. The manipulation of hops today as an integral ingredient in producing craft beers makes for some pretty wildly hoppy beers. (All of which I enjoy immensely, making me more than likely a normal taster.)

Taste is a good case of “more is not better.”

Supertasters find beer incredibly bitter, so much so that they will avoid drinking hoppy beers like IPAs and will not be too terribly enamored of even mildly hopped beers, like most lagers. I also am immune to the burn of alcohol in the beer, something that a supertaster will report when his or her lips touch a high-alcohol beer. Suffice it to say, hard liquor is a no-no for supertasters. Nontasters will pretty much drink and eat anything, so their tolerance for hoppiness is extreme. But they more than likely will not be able to tell the difference between a Columbia hopped beer and a Cascade hopped beer. Supertasters more than likely should be able to discern quite well between these two hops by taste, but unless they have been conditioned to drink beer, they more than likely will first and foremost consider both as just really bitter. So it is normal tasters who have all the fun with tasting hoppy beer. All of this does not mean that supertasters and nontasters won’t enjoy alcoholic beverages. A nontaster will have no trouble gulping down a jalapeño-infused tequila, and a super-taster can be conditioned to drink beer or wine and enjoy those beverages. It has been suggested that upscale chefs are supertasters who have conditioned themselves to overcome the overwhelming effects on their taste buds and to use their supertasting as a tool to create novel dishes. Recently, sour beers or farmhouse ales have become very popular. In this case, brewers of these interesting beers take advantage of the sour taste receptors and combine that with a little hoppiness. Anyone who has tasted a really sour farmhouse ale, though, will recognize that their sour taste receptors are going crazy relative to their bitter receptors.

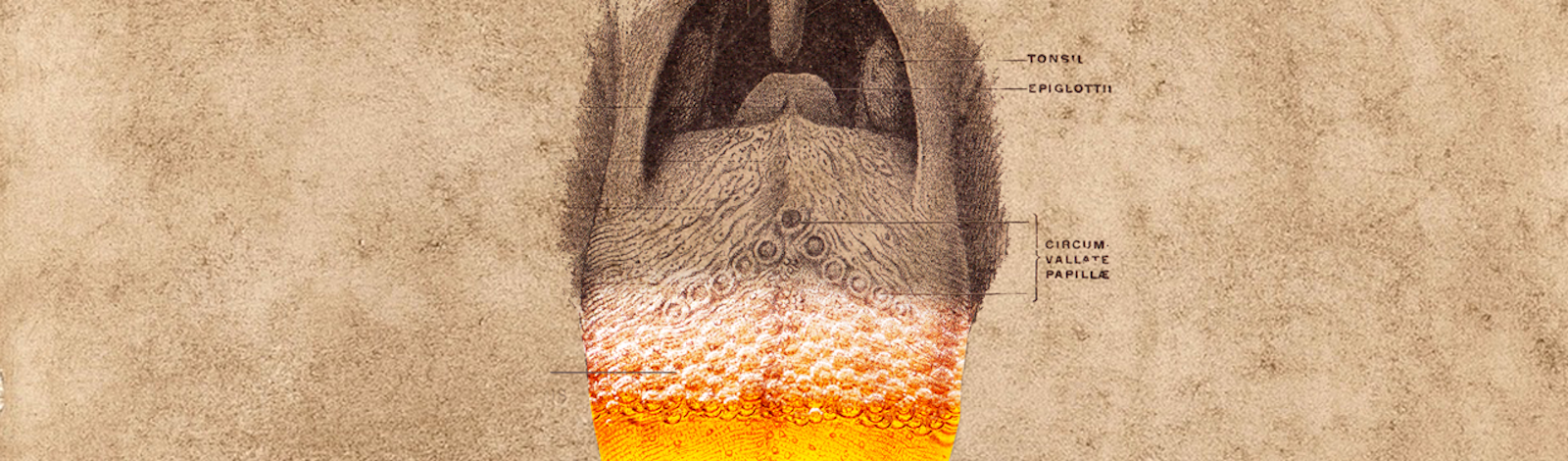

Tasting beer is really a simple reaction of the small chemicals in the brew with receptor molecules on the tongue. But unlike smell, and although taste is combinatorial, the one thing that dictates whether someone can taste, supertaste, or not taste is ultimately caused by the number of taste cells on the tongue. The taste receptor cells are found in bundles of anywhere from 30 to 100 cells within which the taste receptor proteins reside. The bundles of cells are called taste buds, and most of these reside on physical structures of the tongue called papillae.

There are three forms of papillae on the tongue related to where they reside. The fungiform papillae reside on the anterior region of the tongue, look like little mushrooms budding up from the surface, and can have up to two taste buds per papilla. The circumvillae are located in the posterior region of the tongue, and the foliate papillae are located on the sides of the tongue. Taste papillae are also found on the upper side of the mouth (the palate) and in the throat. Taste cells have also been found in the lungs, but their function in this tissue is unknown.

The density of papillae on the tongue is directly correlated to being a supertaster (more than 30 per 100 mm2), a taster (15 to 30 per 100 mm2), and a nontaster (less than 15 per 100 mm2). In this case, instead of the genes for the taste receptors being the ultimate cause of supertasting, an underlying developmental process is involved. How the tongue develops its papillae has recently been deciphered, and interesting hypotheses about the evolution of the arrangement and number of papillae formed during development are being tested. One immediate result of this work is the discovery of the strange phenomenon that teeth and papillae are patterned with similar genes.

What is an effective technique for examining how many papillae someone has in a given area of the tongue? All of them involve darkening it, and the most enjoyable is to swirl red wine in the mouth and over the tongue. If done correctly, you will be able to see little lumps of tissue on the tongue that are the papillae. Next, take a piece of three-hole notebook paper. The punched holes are about 6 or so millimeters in diameter, and a piece of paper torn off with one of these holes can be placed over the darkened tongue. Now simply count the number of papillae you see in the punched hole. If you have fewer than 4 papillae, you are more than likely a nontaster, whereas from 4 to 8 papillae would suggest that you are a taster. Anything over 8 would indicate that you are a supertaster or a super-supertaster.

Rob DeSalle is curator of entomology in the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He is author or coauthor of dozens of books, several based upon exhibitions at the AMNH, including The Brain: Big Bangs, Behaviors, and Beliefs and A Natural History of Wine.

Excerpted fromOur Senses: An Immersive Experience by Rob DeSalle. Copyright © 2017 by Rob DeSalle. Excerpted by permission of Yale University Press.