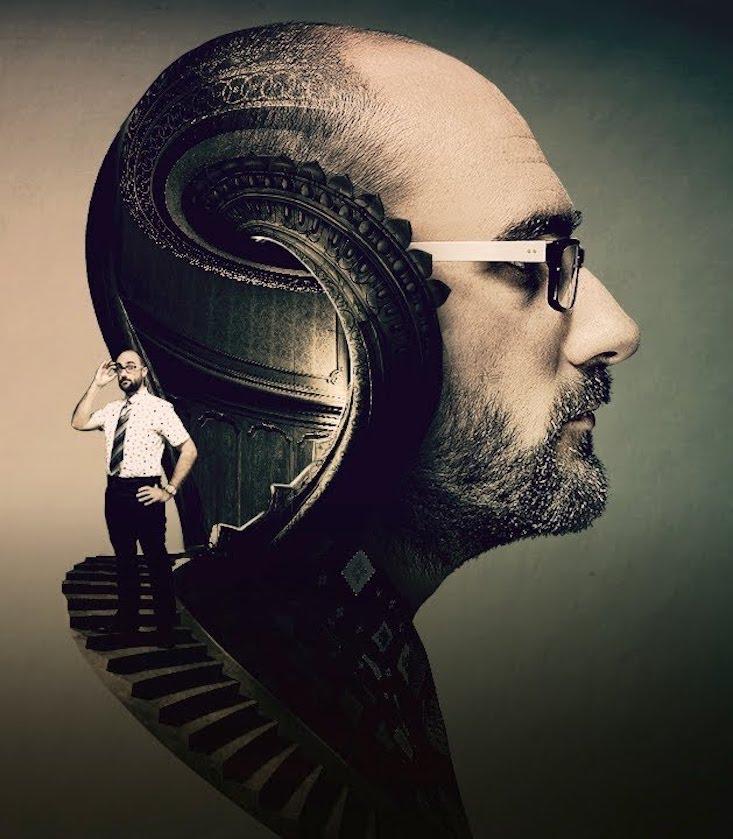

What does the science educator of today look like? With the rise of streaming technologies, would-be educators no longer need a network deal to reach an audience. Case in point: Michael Stevens.

Stevens created Vsauce, a YouTube channel originally focusing on games that amassed a large following—over 18 million subscribers and 1.2 billion views after 10 years. Publishing on YouTube gave Stevens the freedom to experiment, so he began to explore his lifelong interest in science, inspired by the science educators of his own childhood, like Mr. Wizard and Beakman.

Today his videos range from 10 to 30 minutes and blend philosophy, mathematics, and science together: “Which way is down?” and “How to count past infinity” are good examples. Stevens’ success spurred the creation of Mind Field, his YouTube Red series that focuses on how we study our psychology. Recently, Stevens has been touring with Mythbuster Adam Savage for Brain Candy Live and preparing for Mind Field’s second season, which premiered December 6th.

Nautilus caught up with Stevens to discuss science, spreading contagious curiosity, and season two.

How has the internet affected science communication and education?

I think we’ve learned that we underestimate how smart people are. Before the internet was there to allow people to access all kinds of content, there was this fear that you don’t want to get too deep into something, with too many details, because it’s just boring and no one cares. Then, all of a sudden, with the internet, you had these independent content creators making things that weren’t afraid to dive into, say, the mathematics of the fractal dimension. Pulling no punches, literally graduate level courses that were just out there, and they’re being watched by people with all kinds of jobs and children, because we find these things so cool. Even if you don’t understand all of it right away, just watch it again. There’s a rewind button, there’s a scroll bar—it’s like a book. We found that people are much hungrier for information and less afraid of information than we may have thought before.

Why is science communication valuable in the first place?

Science communication allows people to feel more comfortable about asking questions and not knowing answers. You learn through science what its limitations are—critical thinking skills that make you better in more ways than you might think. It doesn’t just make you better at taking tests or being an egghead. It makes you a better person, a better citizen.

How do you spread curiosity about science?

Part of it is just being passionate about your topics. If I don’t care about a topic, I’m not going to make a video about it, because somebody else probably cares more about it, and they should. Instead I only cover what I am so excited about that, whether I make an episode or not, if you run into me on the street, I’m going to want to talk about it. That is really authentic. It’s what people demand now that they have so many choices, and that’s what makes it so contagious, that you see how real my passion is for it.

“Wow, YouTube is pretty powerful.”

How has the authority of science changed?

Science communicators have a growing responsibility to show their work, and their sources, and links to one another, and invite people to think about why scientists believe what they believe. It’s not enough to just be an authoritative voice now—you have to invite people into the conversation. You have to overestimate what they’re capable of understanding, but underestimate their vocabularies. I say that because we often use words to describe entire concepts. Just because you know the word, doesn’t mean you actually understand the concept.

What is your new YouTube Red series, Mind Field, about?

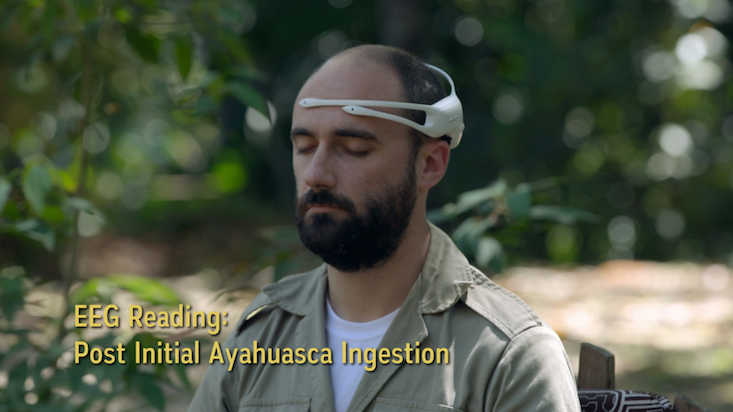

Mind Field is a return to my background in psychology. What I want to do in it is focus on how you study the mind and the brain. We have to be really clever. You can’t just take my brain out and change something about it, and put it back in, and ask me what happened. In the series, I’m setting up, with experts, demonstrations and experiments on the mind. The audience gets to follow that path, see how we do it, and what we do with the results.

What’s been your favorite experience doing Mind Field so far?

One episode this season is about the power of suggestion. We worked with McGill University on a mind-warping study on the placebo effect, specifically accessory-assisted placebo. They demonstrate that they’re able to convince adults, even neuroscientists, that they’ve invented a machine that can read your mind and implant thoughts into your head. It was a look into how much we trust science. We wore lab coats, we had fancy looking computers, and fancy looking equipment and scanners, but it was just an act. We are so enchanted by the idea of science and neuroscience that we trust it and believe what it says it can do.

What’s coming up that you’re excited about?

I’m really excited to release our first episode of season two, in which we create the trolley problem in real life. This is the famous hypothetical in philosophy in which a train is about to hit five people, but you can pull a switch and it will switch tracks and only hit one person. If you do nothing, five people die, but if you pull a switch, only one person does, but you’re directly responsible for that. We’ve learned a lot about ethical psychology by asking this on surveys, but it’s never really been done in real life. Can you making a participant believe that lives are in their hands and that their decisions are leading to death? We worked with internal review boards and a number of ethicists and psychiatrists and counselors to put this experiment together.

What are your favorite big questions?

My favorite big questions are things like, “What is random? What is information?” Probably I’d say my favorite though is the classic conundrum of what comes first? Do we discover mathematics or are we inventing it? How does an orbiting planet know that it needs to factor in pi when it moves? Pi is an irrational number. You can’t even put all the digits into the universe, but yet it’s the ratio between a circumference and diameter. It’s there, but why?

Are there any topics that you’ve avoided?

It’s usually just a matter of having the time, but there are definitely topics that I just don’t feel ready for yet. One is the human experience of death. That is not something that I want to make a 30-minute episode about. That’s something that deserves an entire season worth of content, and I’ve got a lot of ideas for how I want to do that. In fact, when I first pitched Mind Field, I pitched a number of different shows, and one was just multiple shows about death and what we know about it, how humans interpret it.

How did you get interested in science?

You could trace it all the way back to my dad and growing up. He was a chemist, and he loved learning. He was an autodidact, he would just get into something and then self-teach himself reading books. He took some college classes when he was an adult on classical music because he was like, “I want to know classical music.” I’ve just witnessed my own father going through these phases of collecting everything Beethoven ever wrote, and then he’d get really into collecting elements. I joined in, I loved it, I smelled a bunch of burning sulfur, which was not fun. He had a lab in the basement, and I was also just infatuated with Bill Nye, and Mr. Wizard, and Beakman’s World, and the thrill of finding things out. It wasn’t just the classical schoolbook topics of chemistry and mass, but it was literature and it was sports figures, and it was anything that I could be curious about, I was.

How did you become a science communicator?

I was working in a research lab at the University of Chicago, in the psychology department, when YouTube was invented. I said, “Wow, YouTube is pretty powerful.” I had been doing a lot of theater simultaneously. All of a sudden YouTube was there as a place where I could marry both of my interests—perform but also spread contagious curiosity. I started making episodes that addressed topics like deja vu, how deep can a hole be dug, and why is spicy food spicy. There was an enormous demand for that. We want to know. You can’t help but read a title asking what color a mirror is and go, “Well, now I have to click and find out.”

Victor Gomes is an editorial intern at Nautilus.

WATCH: What’s missing from the public perception of science.