Local Honduran fishers mostly avoid fishing in Tela Bay on the country’s Caribbean coastline. Nonetheless, they have a name for the shapes and forms on the seafloor that waft in and out of view with the shifting glint of the sun. They call them “rocas” or rocks.

Just over a decade ago, Antal and Alejandra Börcsök, newly-trained divers, heard about the rocas and, curiosity piqued, donned their scuba gear to explore. On the seafloor, rather than inorganic geologic forms, Antal and Alejandra discovered rocks that were very much alive. Everywhere they looked they saw growing, thriving coral.

The Börcsöks knew that Caribbean coral were plagued by disease, bleaching, and death. Yet as novice divers, they hadn’t seen enough to judge Tela’s coral. So, they invited friends who were active in coral monitoring to have a look.

Diseases that have ravaged other Caribbean reefs are apparently absent from Tela Bay.

Back on the surface, Antal recounts how their friends gushed, “That is the greatest reef we’ve ever visited! Is there more like that?” Now, having dived throughout more of Tela Bay than anyone, Antal can say that there is. In fact, there’s a lot more reef like that.

But why so much healthy coral exists is mysterious. “We should have nothing in Tela,” Antal says. “Everything that’s bad, we do in Tela.”

That no one seems to have looked beneath the surface of Tela Bay before the Börcsöks did is probably because it’s such an unlikely spot for a thriving reef. About 10 kilometers west of Tela Bay, the Ulúa River, Honduras’ largest, empties into the Caribbean. It is loaded with sediments, which are typically problematic for coral. Sediments cloud sunlight required for photosynthesis by algae that live inside the coral’s tissues and supply as much as 90 percent of their nutrition. Sediments can also physically smother reefs.

“Not only that,” says Antal, “this is the place where the banana republic started.” In 1913 the United Fruit Company, which later became Chiquita, received concessions from the Honduran government to operate a rail line into the city of Tela as well as 162,000 hectares of land for banana plantations. Today the remains of the 1,000-foot wharf where boatloads of bananas were exported still rise above the surface of the water, but the banana trees have largely been replaced by African oil palms and those plantations have expanded.

Tela receives more than a meter of rainfall a year; as it runs into the bay it brings fertilizers from the plantations with it. Compounding the agricultural runoff is waste from Tela’s roughly 100,000 inhabitants. The city has no sanitation system except for pipes that run directly into the bay.

Corals evolved to live in the sea’s deserts, places where organic molecules like those in fertilizers and sewage are nearly absent. When exposed to elevated concentrations of these nitrogen-rich compounds, they often sicken.

Yet after more than a century of inundation by sediments, agricultural runoff, and sewage, the corals in Tela are unaccountably thriving. The reason the fishers avoid the reef is because it is so abundant and complex that small fish can hide from predation. Big fish don’t bother hunting there, and neither do the fishers.

Discovering the reef galvanized Antal and Alejandra. They started a project to protect it, and within two years saw the passage of a local law to do so. Their company, Tela Marine, partnered with an English tour operator, Project Wallacea, which helps graduate students develop field projects.

Dan Exton, the head of research at Operation Wallacea, recalls standing on the beach in Tela with Antal for the first time and thinking there couldn’t possibly be a coral reef beneath the murky water. “I almost cancelled the dive,” he said. But as soon as he descended, Exton saw “mind-blowing coral. I’d never seen a reef like that. Everywhere you looked, something unusual was happening.”

Since then, Exton has overseen the work of more than 500 students in Tela Bay; their findings confirm the unusual richness of the reef. Whereas at the nearby island of Utila, coral cover—the proportion of a reef’s surface where healthy coral grows—hovers around 20 percent, in Tela it remains more than threefold greater.

Elkhorn and staghorn coral species that are critically endangered in the rest of the Caribbean grow in rich thickets along the bay’s shores. Mountainous star coral, another endangered species, grows in massive plated colonies as big as backyard sheds. Lettuce corals unfurl in long, rich carpets. Their blades form tiny three-dimensional apartments for shrimp, snails, clams, worms, and tiny sea stars, and provide spaces where small fish can hide from predators.

“As far as we know, there isn’t any other reef in the world that looks like this.”

One important observation is that diseases that have ravaged other Caribbean reefs are apparently absent from Tela Bay.

Since 2014, stony coral tissue loss disease has decimated reefs throughout the Caribbean, melting more than 20 species of brain, maze, and pillar coral tissue like hot wax. These species are found in Tela Bay, yet no one has seen the disease there.

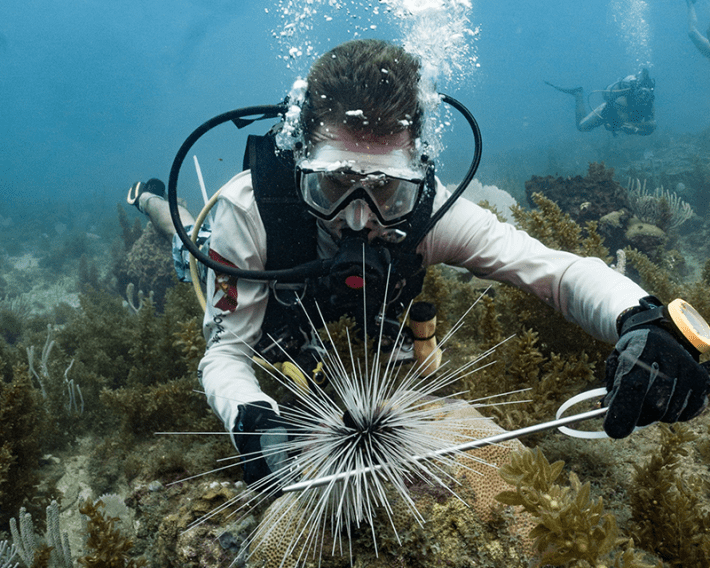

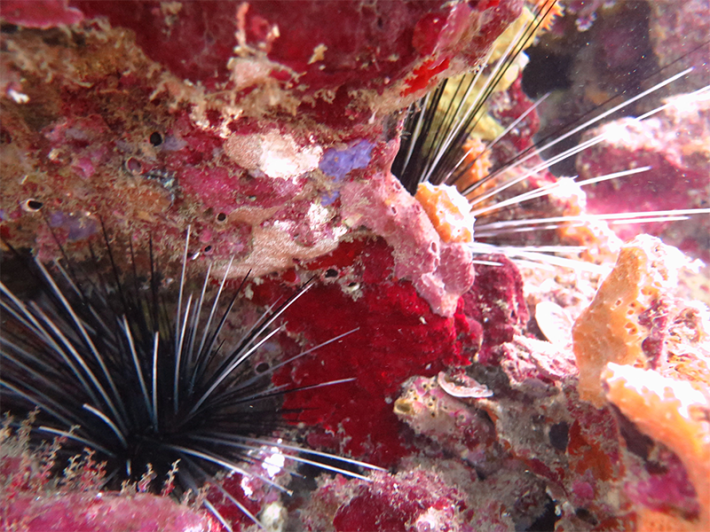

Here and there, the pick-up-sticks spines of sea urchins wave curiously from within crevasses. These clementine-sized urchins are critical to reef health, grazing algae that can easily overgrow coral. In the 1980s an epidemic wiped out urchins throughout the Caribbean, and they have never rebounded. In Tela Bay, the numbers of urchins remain at pre-pandemic levels, roughly 100 times more abundant than elsewhere in the region.

Another outlier are giant barrel sponges. On nearby Roatan, divers used to pose for pictures inside millennium-old sponges so big that the dive spot was referred to as “Texas,” because everything is so big in Texas. But in 2018, an affliction called orange band disease killed the ancient organisms in just four months. In Tela Bay, barrel sponges were unaffected.

One more threat facing reefs is heat. As Earth warms, half of all coral reefs are thought to have already succumbed to bleaching, in which a coral’s symbiotic algae departs the partnership, leaving the coral bereft of color and nutrition. Bleaching is caused by warming waters. Tela Bay’s reefs, however, have handled the heat.

Anne Cohen, a marine biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who searches out heat-tolerant reefs, performed a preliminary estimation of heat stress on Tela Bay’s corals for this article. Her team found that, although sea surface temperatures reached 31 degrees Celsius—hot enough to blanch any reef in Florida—there had been comparatively few episodes of the types of heat waves that are especially conducive to bleaching.

As a result, her lab’s models suggest that bleaching would only have been expected once, in 2017. “It just hasn’t gotten hot enough there,” Cohen says. That jives with Antal’s observations. He rarely sees bleaching in Tela.

In 2018, armed with reef survey data, and working with local NGOs and the Ministry of Agriculture, Tela Marine shepherded an act through Congress establishing the first Marine Wildlife Refuge in Honduras, strengthening protections for Tela Bay from the local to national level.

Scientists searching for healthy coral might have looked in the wrong places.

But just when the future seemed assured, a Chinese company proposed developing an iron mining operation along the Ulúa river. It had the potential to dump heavy metals toxic to marine life into the bay. “That was going to kill the reef, basically in a year,” Antal said.

Ultimately, the mining operation was halted, in part because of public testimony against it, but the threat showed just how little stood between the reef’s survival and economic forces. Even an act of Congress was a flimsy line of defense.

“We realized that the biggest problem was that nobody knew there was a reef there, right?” Antal points out. “So how do we take people to the reef?”

In a place where a small fraction of the population dives, the answer was to bring the reef to them. So, Tela Marine opened the only public aquarium in Central America. Twelve thousand visitors a month already pour through the aquarium doors, which puts it on track to be one of the largest attractions in the country.

An intentional part of the draw is the price of admission: free, except for an eight-minute speech from Antal or one of the aquarists on why the colorful corals, creeping seastars, spiny urchins, and darting fish they are about to see are such a treasure.

While the Börcsöks work to protect the reef, questions remain about what makes it so healthy. Is there something about the bay that protects its corals from bleaching? Have the corals adapted to a century of runoff? How do they thrive with so much sediment? Is there something special about their symbiotic algae? What prevents diseases from spreading in Tela when they rampage through the rest of the Caribbean? Are the coral, urchins, or sponges genetically different? Most importantly, can this reef continue to survive?

Currently, answers are unknown. Like the public, few scientists are aware of the reef’s existence. Aside from Operation Wallacea, little scientific attention has been paid to the reef. Research has largely involved observation and monitoring, although plans for more detailed studies are now in the works.

Even before those questions are answered, when Antal stands before a crowd of enthusiastic aquarium visitors he can already say, “We have something that we can be proud of in Honduras. This reef is unique. As far as we know, there isn’t any other reef in the world that looks like this.”

So far, that is. Dan Exton notes that the implications of finding the reef stretch well beyond Tela Bay. “It can’t be the only one out there that’s like it,” he says. Exton suspects that scientists searching for healthy coral might have looked in the wrong places as seas shift to warmer, more polluted conditions.

“If you were to look at other turbid, cloudy, impacted bays around the Caribbean, you may well find other healthy reefs,” says Exton.

To him that’s a reason for optimism. ”We get so bogged down in coral reef science by the idea that, in 50 years’ time, corals won’t exist anymore,” Exton continues. “I think there’s a lot more hope for reefs than we give them credit for sometimes. For me, my personal hope comes from Tela Bay.” ![]()

Lead image: Tela Bay, Honduras is hot, polluted, and the last place anyone expected to find a thriving coral reef — but species dying out elsewhere in the Caribbean have continued to flourish in its waters. Photo by Antal Börcsök