There was no single job title for those who practiced science prior to 1834. Naturalists, philosophers, and savans tramped around collecting specimens, recorded astral activity, or combusted chemicals in labs, but not as “scientists.” When William Whewell proposed this term, he hoped it would consolidate science, which he worried otherwise lacked “all traces of unity.” Whewell saw scientists as analogous to artists. Just “as a Musician, Painter, or Poet,” are united in pursuit of a common goal—the beautiful—Whewell believed a botanist, physicist, or chemist should be united in their common pursuit of understanding nature.

Built into his concept of what it means to be a scientist was a relation between what the poet and philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson, a contemporary of Whewell, called “Each and All”: an attention to the particular that keeps the big picture in sight. For Emerson, the “All” was Nature and the “Each” could be a shell, or bird, a humblebee, or a Rhododendron. The point of science, according to Whewell and Emerson, was to investigate the relation between these two scales. Today, we have other terminology for “Each and All”: the reflection within the local, for example, of global phenomenon. Consciousness emerging from the activity of individual neurons. Spring flowers in Concord whose earlier blooming reflect changes in planetary climate patterns.

In the video below, Harvard professor Elisa New sits down with former Vice President Al Gore to discuss Emerson’s poem, “Each and All,” in conjunction with 19th-century science, 20th-century space exploration, and contemporary climate change. The conversation, along with others featured on Nautilus, are part of New’s Poetry in America project. New’s conversation with Gore is part of a new Poetry in America initiative focused on the “Poetry of Earth, Sea, and Sky.”

It makes good sense to pair Emerson and Gore. Both powerfully shaped the public discourse of their time as popular lecturers. And though neither is a scientist, both were transformed by science. The year before Whewell proposed “scientist” as a term, Emerson experienced a scientific conversion wandering among natural history cabinets in Paris. Wooed by the formal connections he witnessed between shells and stuffed birds, he announced, “I will become a naturalist!” Instead, he quit the ministry and became a writer. Similarly, Gore would have been a very different politician if he had not learned as an undergraduate of research into ice cores revealing rising global levels of CO2. (I love imagining what Emerson would have done if he could have turned his lectures, as Gore did with An Inconvenient Truth, into a film. It would have been weird.)

Beyond a deep interest in science, Emerson and Gore also share a common belief in the connection of humans to the non-human world, and the importance of focusing on the “All” even as we study or celebrate the “Each.” Gore’s diagnosis of the current global climate crisis as a manifestation of inward spiritual crisis is Emersonianism, only inverted. Where Emerson found in Nature reflections of human’s divinely ordered intellect, Gore sees recent extreme weather patterns as the result of an imbalance in “inner ecology.”

It’s high time we transformed the way we function within human society for the sake of this planetary interconnection.

The concept of ecology wasn’t available to Emerson in the 1840s, when he published “Each and All,” but the idea of a holistic “composition” or even “argument” to the natural world was central to his thinking. For both Emerson and Gore, science at its best is able to deliver a big-picture perspective to the masses, that same unity of vision that Whewell sought when he proposed that scientists unite under a single job description.

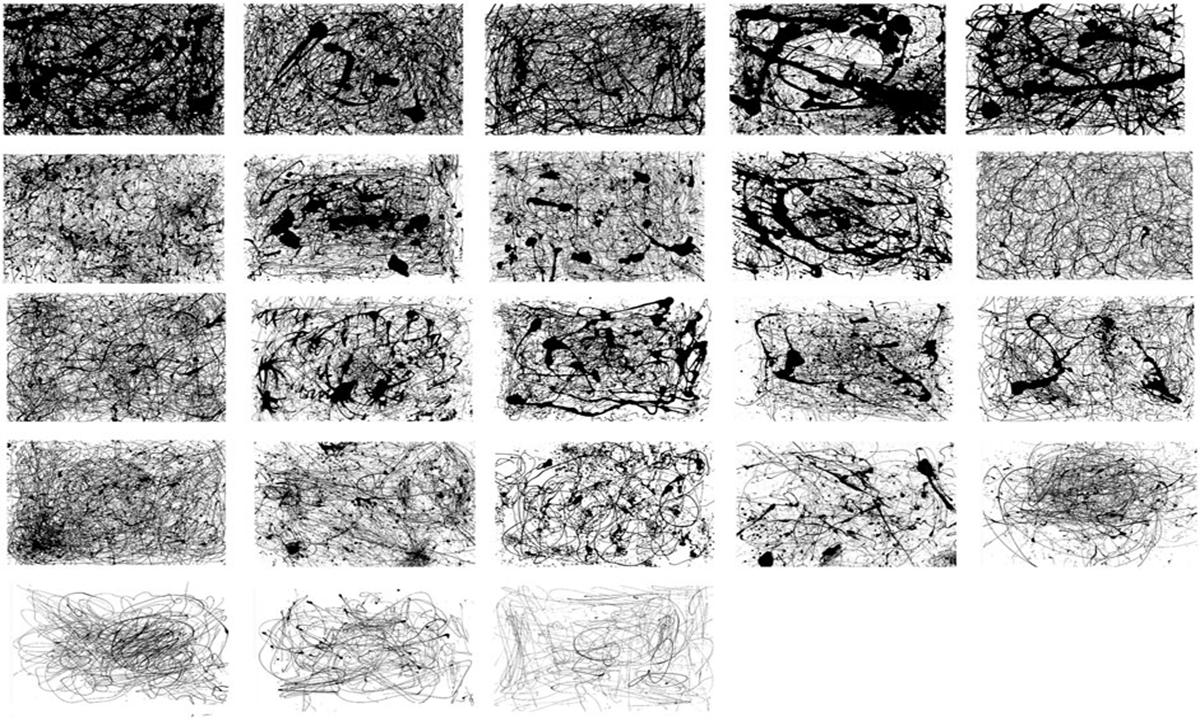

On the flip side, for both Emerson and Gore, too much emphasis on division—including the technologies of classification upon which much of modern science depends—is a problem. It may sound strange to talk about classification as a technology, but in Emerson’s time, scientists were still debating the benefits of an artificial system of classification (think Linneaus, grouping flowers by the number of their stamens) versus a natural one (based on the overall morphology, development, and function of a plant).

Emerson’s period saw a professionalization of the sciences, which, contrary to Whewell’s vision for unification, ultimately required division, as scientists further defined and differentiated their objects of study and their methods. In Emerson’s terminology, the “Each” necessarily came to define fields within science. But Gore’s era, our own, has given us new technologies that make a vision of the “All” ever more available, a perspective that the global nature of climate change further reinforces. Gore describes the impact of the Apollo photos of “Earth Rise” on human consciousness of the planet as a unified whole. A year and a half after the publication of these photos: the first Earth Day.

All these ideas play out in Gore’s conversation with New. Perhaps what’s most striking in the thought of Gore as a modern Emerson, however, is the vision each of these men holds for the power of the social sphere. For Emerson, humans exist interdependently with all of Nature. The woods and fields “nod to me, and I to them,” he writes. In a journal entry that evolved into “Each and All,” and written the same year that William Whewell defined what it might mean to be a “scientist,” Emerson records an experience of bringing home shells only to find them dull and dry. In the poem, he describes how they have “left their beauty on the shore.” But in his journal entry, he calls them “wet and social by the sea and under the sky.” For Gore, it’s high time we transformed the way we function within human society for the sake of this planetary interconnection.

If the situation Gore calls attention to weren’t so drastic, he might end his lectures with these words from Emerson’s poem: “All are needed by each one; / Nothing is fair or good alone.” As it is, Gore is fond of finishing his talks by calling political will “a renewable resource,” a renewable which depends, like Emerson’s shells, on collective composition, for its beauty.

Gillian Osborne is the head teaching instructor and course manager for the Poetry in America course series at the Harvard Extension School, a curriculum developer for Verse Video Education, and the co-editor of Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field.

Elisa New is the creator of the multi-platform educational initiative Poetry in America, the host and director of the Poetry in America television series, the director of Verse Video Education, and the Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature at Harvard University, where she teaches courses in classic American literature from the Puritans through the present day.