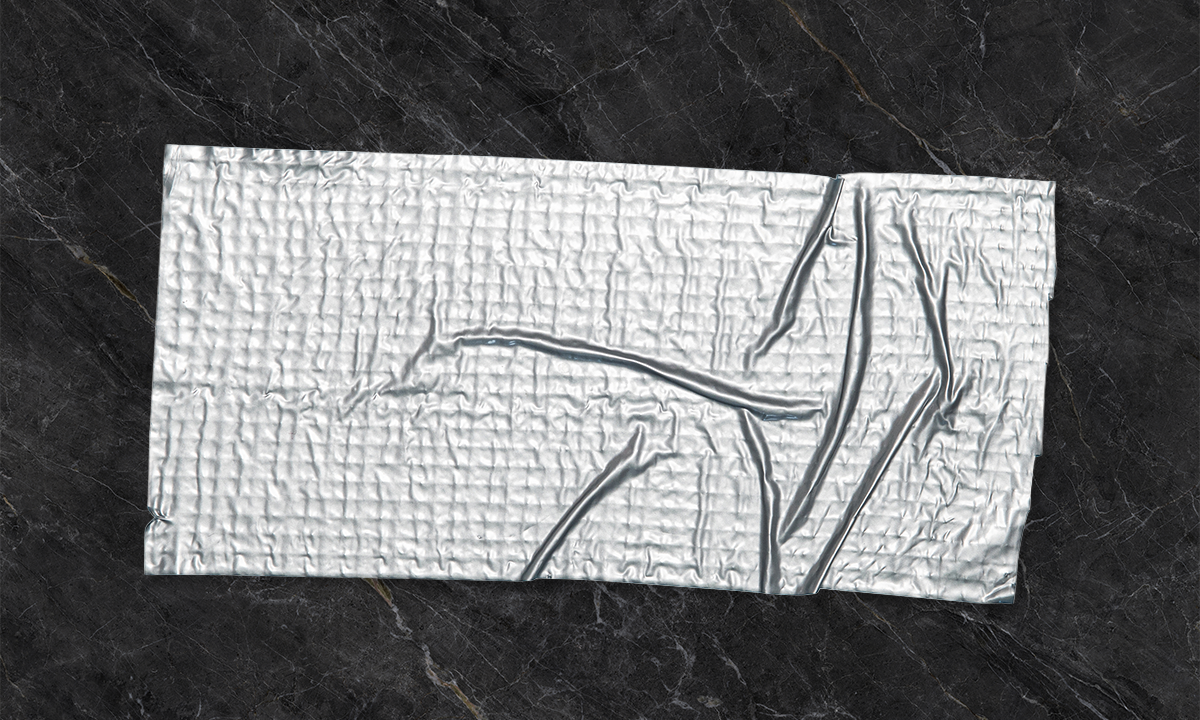

By the time Donald Johnson got the call to come to the crime scene, the victim had been dead for hours. A first responder opened the apartment door to find a woman lying on the edge of her bed, nude from the waist down, bound and gagged with duct tape. She had been bludgeoned to death. The homicide detectives needed an expert to gather the evidence. That was where Johnson came in.

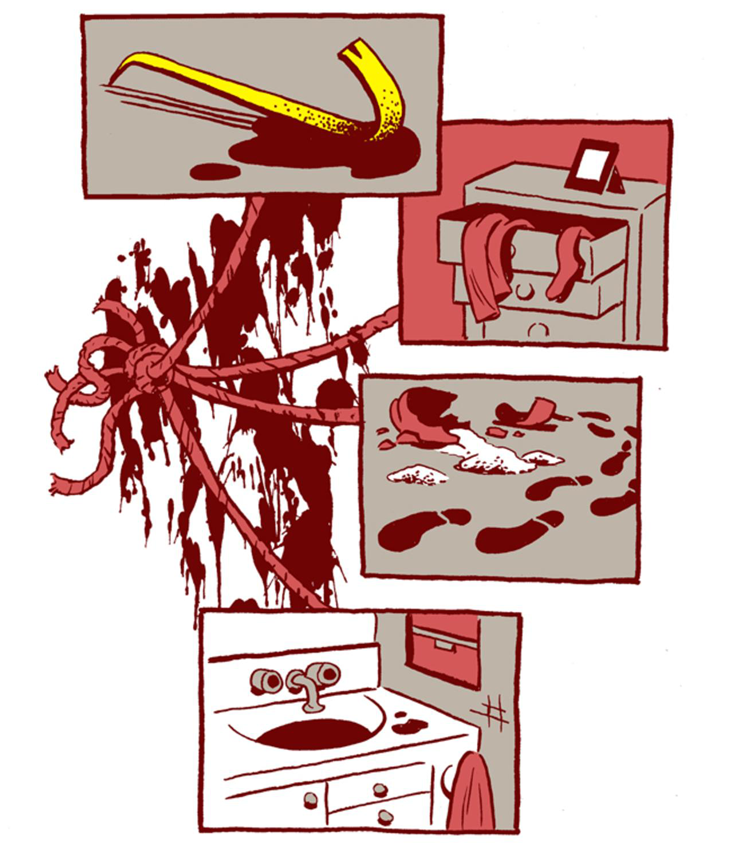

Then a senior criminalist for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Johnson surveyed the apartment. Shards of ceramic lay on the kitchen floor, remnants from a broken jar that once held flour. Johnson noticed two sets of footprints in the flour, ignaling to him that there were two assailants. Clothes spilled from a chest against the wall across from the bed. From the mangled lock, Johnson could tell the chest had been forcibly opened, perhaps with a crowbar. There was also blood on the lock, with a trail of drops on the floor leading to the sink where the assailant had washed his hands.

It was more than enough blood evidence for Johnson to get a complete DNA profile.

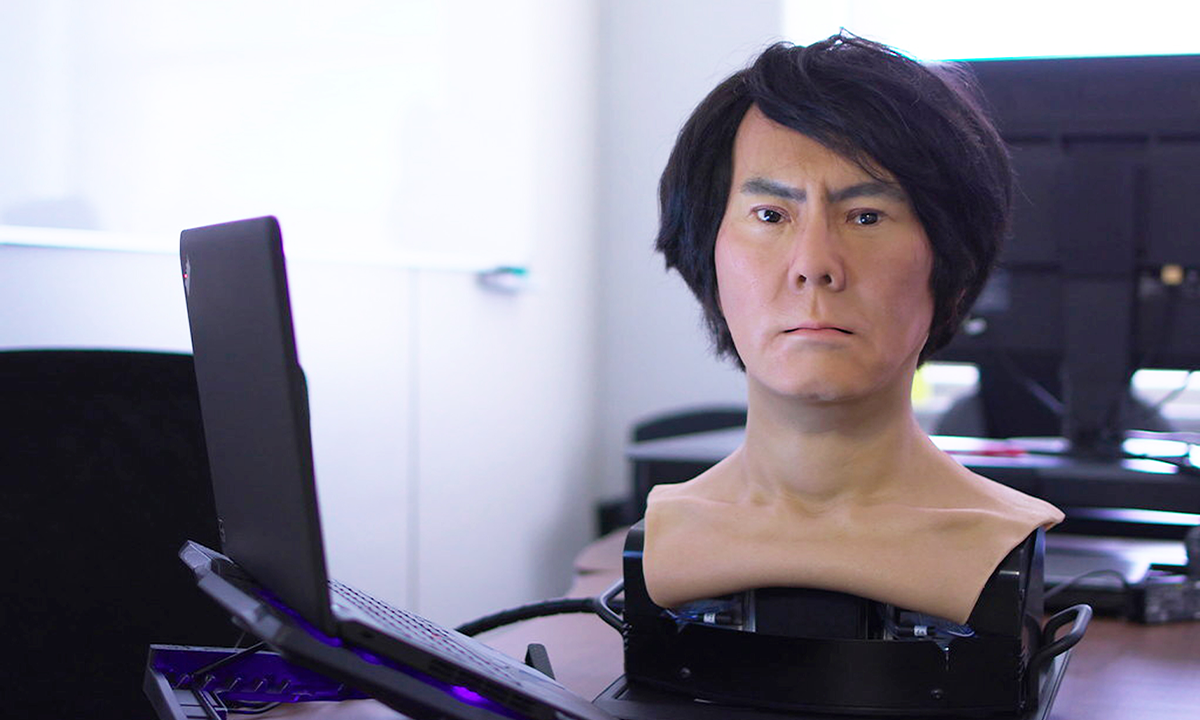

This ghastly crime happened 28 years ago, but a replica of the scene is on display in a classroom at the Hertzberg-Davis Forensic Science Center at California State University, Los Angeles, where Johnson, 60, has worked as an associate professor in the criminalistics program since 2003, and is currently working on new forensic technology called the Spatter Origin Revealing System to improve how investigators can solve crimes by examining blood.

Aside from serving students, the Forensic Science Center is also the working crime lab for the Los Angeles Police Department and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. As the largest crime lab in the country, second only to the F.B.I.’s, the Forensic Science Center conducts DNA analysis, questionable documents analysis, narcotics testing, trace evidence analysis, and ballistics testing, in addition to blood spatter analysis. For teaching purposes, Johnson often recreates real crime scenes that he worked on as a criminalist before he left the field in 2003. For this one he used a mannequin and sterilized pig blood.

“You know how some hospitals are teaching hospitals?” Johnson says. “Well, we are a teaching crime lab.” But Johnson is no fictional Gil Grissom or Dexter Morgan. He’s the real deal. With graying hair parted down the side, kind and heavy eyes hemmed in by lines underneath, and a permanent hint of a smile, he looks like a cross between the actor Mark Harmon and Mr. Rogers. He speaks slowly and deliberately, often with his hand on his chin, and wears a tiny Sherlock Holmes pin on his jacket. A taxidermy bat is mounted on a wall in his office, a tribute to his love for the creatures since his childhood, and a framed picture of Batman hangs outside his door. He also keeps a 30-year-old python snakeskin nearby, a gift given to him by another criminalist after they performed a necropsy revealing the python’s cause of death was a rat entangled in its intestines. His motorcycle helmet and a first place trophy from his competitive aerobatic plane flying days sit on top of a filing cabinet, both a testament to his love of life and to the tremendous precision required to operate both machines. And of course an entire wall is lined with shelves of forensic science books.

The goal is to develop a handheld device or a program for a tablet for use in the field.

Johnson began his career as a narcotics chemist with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. He was trained to test for and identify illicit drugs such as cocaine and meth, operating out of clandestine laboratories. But he always wanted to work in the violent crimes unit. When it came to death and murder investigations, it was “something I had always found fascinating and intriguing,” he says. As a child he loved biology, and recalls a writing assignment from third grade, which his mother found and sent to him when he joined the sheriff’s department. The prompt asked: If you had three wishes, what would you wish for?

“I wished for a robot, a helicopter, and a crime lab in my bedroom,” he says. Johnson worked as an autopsy technician for the Lucas County Coroners Office while attending the Medical College of Ohio in Toledo, his hometown. He then moved to Los Angeles to attend California State University, Los Angeles as a biology major. To support himself through school he worked as a mortician. He then attended the UCLA School of Medicine and worked in the Los Angeles County Department of Coroner.

His passion for biology merged with his growing zeal for the justice system. Since 1989, Johnson has devoted his professional life to forensic science and its application in law enforcement. When he started, the scope of blood and DNA analysis was limited. Now criminalists can get a full DNA profile from only a few millimeters of blood.

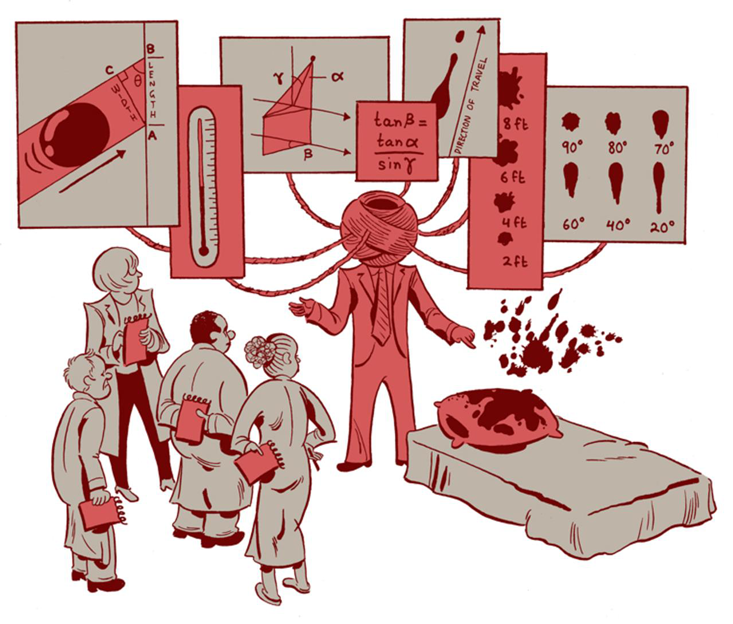

For criminalists, blood-spatter analysis—like the kind used on drops found near the victim who had been bludgeoned—has long been a tool to determine how crimes occurred. Based on the varying sizes and shapes of the blood drops, investigators can often tell what type of weapon caused the spatter, determine the general area where the attack occurred, and track the positions of the victim.

“I wished for a robot, a helicopter, and a crime lab in my bedroom.”

Blood usually travels in the shape of a sphere, and when it strikes a wall, for example, it generally takes the shape of an ellipse with a tail forming in the direction the blood traveled. First, the criminalists determine the angle of blood spatter impact using a complex mathematic formula. Then, once enough measurements have been taken, they determine the area of origin by tracing the blood drops backward, marking the routes by using string, mapping out an intricate web. When all the strings begin to intersect, the general vicinity of the attack has been pinpointed.

“Oftentimes blood spatter analysis is used to test an alibi, such as self-defense,” Johnson says. “Other times it’s used to reconstruct events around a crime for a thorough understanding of the case.”

Read more Narratively: The Boy Who Cried Abuse

Say a criminalist is investigating a potential homicide case involving blunt force trauma to a victim’s head, and the accused claims he was attacked and struck the victim out of self-defense. How can his claim be tested?

Blood splatter analysis can help answer questions like this: Where was the victim’s head positioned when the blow was delivered? Was it three feet or six feet from the floor, and how far from the wall? If the blows were delivered closer to the ground—say, around a bed or somewhere a victim was seated—it might be harder for the defendant to argue self-defense.

This method of blood spatter analysis involves extensive photographing of the crime scene, then enlarging the photos to take measurements. Since the measurements are taken by hand and the math calculations are inputted into a calculator, there’s always the potential for human error. Also, blood evidence contamination can occur when criminalists work directly with their hands, which is why Johnson and his team have been creating a more sophisticated and efficient blood spatter analysis system.

Along with David Raymond, who specializes in forensic biomechanics and experimental mechanics, and senior engineering students Angela Wu, Jose Rodriguez, Joel Negrete, and Kevin Tepas, Johnson and his team are seeking to revolutionize how blood spatter evidence is analyzed in the field. Current methods of bloodstain pattern analysis can only give investigators an estimate of the spatter impact angle because “issues related to the ballistic path of the droplet preclude us from accepting this angle as absolute,” according to the book Bloodstain Pattern Analysis by criminalists Tom Bevel and Ross Gardner. “As a rule, impact angles are considered to be accurate within 5 to 7 degrees.” The current trigonometric math model doesn’t consider air drag, gravity, or room temperature when determining the flight path of a blood droplet; it assumes that the blood drops traveled in a straight line. Johnson and his engineering team are seeking to identify a better math model that will take all those variables into consideration.

“I have a special gift, if you will, to help man and the community.”

The engineering students spent the fall 2013 academic quarter researching current bloodstain pattern analysis methods. In 2014, they worked on developing a prototype imaging system that can simulate the exact same conditions of the field, and hopefully produce a more accurate bloodstain measurement and angle of impact by converting pixels from a digital blood drop image into centimeters. This process will also cut down the hours it takes to “string” a crime scene by hand.

Read more Narratively: After Years of Tumors, Growing a Baby Instead

The Spatter Origin Revealing System is still in its infancy. The goal is to develop a handheld device or a program for a tablet, which they can give to the Los Angeles police and sheriff’s investigators—and eventually to the entire forensic community—for use in the field.

“L.A. is a hub. It’s a kingpin, if you will, when it comes to forensic science,” Raymond says. “When other forensic experts begin to see what we are doing, I think it’s just going to spread.”

Eventually, in addition to taking more accurate bloodstain measurements from a digital image versus measurements taken by hand with a ruler, they say the technology will also be able to identify the blood spatter area of origin within a three-dimensional space (the actual crime scene) and produce a report for investigators with a snap of a camera shutter.

One of the last cases Johnson worked was in 2001. A family was murdered, including an 8-year-old girl and her 79-year-old grandmother. Before the girl was murdered, the killers raped and sodomized her. As the criminalist working the case, Johnson was called to testify. The extended family of the deceased was there in court. Johnson would never forget the moment when he was asked about the little girl’s sexual assault.

“When I said that I found semen in the vaginal sample and the rectal sample, [there was] this terrible moaning cry from the family. It just stopped the court and everyone was silent,” Johnson says. “Just this agonizing cry.”

For Johnson the only saving grace was that he was able to provide the courts with the needed forensic information to administer justice. For many criminalists, that attitude helps them cope with the especially brutal nature of their jobs.

Read more Narratively: How to Survive When Everything You Eat Is Poison

“I have a special gift, if you will, to help man and the community,” Johnson says. “The thing is that you have to be detached. It’s like being a physician. You have to be concerned, but keep your distance.”

But he can only detach so much. After seeing the child who was raped and killed, Johnson thought about other ways to help victims. Being a criminalist is largely reactionary, he says. A crime is committed, and then the criminalist responds. That was part of the impetus for Johnson to retire from fieldwork and go into teaching full-time.

“I thought through teaching I could help others,” he says, “and they in turn could help victims.”

Blake Morris is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared on Patch.com and MusicGlutton.com.

Ben Juers is a Sydney-based cartoonist whose work has appeared in The Lifted Brow, Seven Days, and the Australian Book Review.

This article was originally published on Narratively. Narratively is a digital publication that looks beyond the news headlines and clickbait, focusing on ordinary people with extraordinary stories.