The natural world is a feast of color and pattern, but what is it all for? An orange tiger seems awfully conspicuous stalking its prey. Why not hide in the foliage with green or brown fur? Multiple species of tiny yellow damselfish swim over and around coral reefs. How do they mate with the right species, when they all look the same? Fresh revelations about the hows and whys of animal coloration are revealed in David Attenborough’s Life in Color, a documentary available on Netflix. Life in Color is the recipient of the 2021 Jackson Wild media award, one of the highest of recognitions given to films about nature. Jackson Wild has showcased outstanding films focused on science and conservation for 30 years. Located in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the organization is dedicated to making global impacts through visual storytelling.

And of course David Attenborough is—David Attenborough. The world’s foremost communicator about the natural world, Attenborough has brought the mysteries of the wild to us for nearly 70 years. With Life in Color, Attenborough returns to one his longest-standing fascinations. His first documentary series, The Pattern of Animals, appeared in black-and-white, in 1953. If he could have seen then what we can see now! His new series, produced by Humble Bee Films, offers a unique and literally eye-opening window onto both the mechanics and utility of animal coloration. Life in Color also showcases breakthrough image-making technology that allows humans to see more than meets the eye. The first two films in the series delve into a literal rainbow of animal stories, and the third film looks behind the scenes at how some of the photography was achieved.

Nautilus sat down with series producer Sharmila Choudhury and director Adam Geiger for insight into superb filmmaking in which we learn that tigers look brightly marked to us, but are nearly invisible to the deer they hunt. The color orange registers to deer as brown, which is much harder to discern through trees and branches. Damselfish species can indeed recognize differences in patterning that is invisible to the human eye. It turns out we can’t see in the ultraviolet range in which much of the rest of the natural world operates. It’s a whole new world out there—hiding in plain sight.

Your films highlight the surprising ways that animals utilize color—why is that important?

Sharmila Choudhury: We take for granted that the natural world is so colorful. For us it’s a source of beauty, but for many animals it’s actually a very important tool for survival. So, animals use colors for all kinds of reasons, to attract a mate or fight off a rival or hide from a predator.

These films are very ambitious—how did you manage to deal with all the different locations and stories?

Adam Geiger: My role in this series was as the Australian Director. It really fell on Sharmila Choudhury and Stephen Dunleavy from Humble Bee Films, and Colette Beaudry from SeaLight Pictures, to work out the storylines. I directed all the underwater segments.

You have been obsessed with underwater photography for a long time.

Geiger: I really became interested in photography taking underwater still photographs. It’s something I’ve always loved. That led me more into wanting to know what I was photographing, what I was seeing. That led me into getting a degree in marine science, and ultimately making films about the underwater world.

We’ve only just scratched the surface, but I think we’re getting a tiny glimpse into a world that’s long been hidden from our eyes.

Over the years you’ve observed this tremendous pressure on natural systems. How can advances in the powers of observation, in camera technology, help alleviate some of that pressure?

Geiger: Over the few years that I’ve been diving, I have seen the degradation of the marine environment. You can’t really go anywhere anymore without finding plastic, for example. I grew up on Martha’s Vineyard, and I’ve seen massive changes in the marine life around that place. Species not showing up anymore, that sort of thing. It’s really sad.

Advances in digital cameras allow us to document things that may be lost in the not-too-distant future. The existence of coral reefs is not assured by any stretch. The same is true even in temperate waters, where whole ecosystems have shifted due to overfishing and pollution. The camera technologies, the ability to get down there and record things that are new to science, to collect new information, is really valuable. It creates a record and helps us understand what’s happening in the natural world.

One story that was very surprising for me is about how the coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef actually happens. The animal ejects the algae that gives it color in order to maximize its capacity to withstand the intensity of the sun—it changes color to give itself an approximation of SPF.

Geiger: The coral makes this fluorescent color change. It’s almost screaming for help, if you will. We learned through this film that color change can be very specifically directed at the animal trying to save itself.

There has been a highly significant increase in what we understand about how animals use color. The technology, new cameras, have helped science understand it better.

Choudhury: We’ve known for quite some time that many animals see colors differently than we do. Some see fewer colors, but many of them—birds, insects, and fish—see more. They see into the ultraviolet range, and this has been the challenge. Neither the science nor the technology had the capacity to understand what animals were seeing, or to visualize it for our human eyes. To be able to overcome those hurdles, we teamed up with scientists who were doing some of the cutting edge research on animal vision, and they had already unraveled some of the new behaviors or new understandings of animal color vision.

Much of the new technology that helps make this visible for the human eye was in its infancy, not meant for broadcast. So we had to adapt those cameras to allow us to visualize that for our audiences. We’ve only just scratched the surface, but I think we’re getting a tiny glimpse into a world that’s long been hidden from our eyes.

What are some examples of the equipment, the challenges, and how you had to “push the envelope,” as you describe it?

Choudhury: Ultraviolet cameras have been around for some time, but they can only film in the ultraviolet range—registering only the ultraviolet colors. They can’t film simultaneously in what we call the red-green-blue range, which describes our vision. So, we had to adapt and set up two cameras side by side on a beam splitter system. This allowed us to seamlessly switch from our vision to a butterfly’s vision, for example.

The butterfly scientist advising us knew his study subjects were highly reflective in the ultraviolet range, but he had only inferred this from graphed behavior patterns. But with our cameras, for the first time, he was able to see how the butterflies use the ultraviolet light in action, and he was absolutely thrilled by that.

How does your camera array work?

Choudhury: We use two cameras and an ultraviolet filter. The filter allows only ultraviolet rays to go into one camera. The other color waves get bounced off a mirror into the second camera, which then shows us an image as we would see with our eyes. You can switch back and forth between the ultraviolet and red-green-blue color images.

So there’s two different views of the same scene, one as we see it and one as other animals see it. And what did that help you to uncover?

Choudhury: A really extraordinary sequence—I think my favorite one—was filmed with specialist cameras underwater on the Great Barrier Reef with tiny shoals of yellow fish. They all look identical to our eyes, but when you view them through the ultraviolet camera, you see that there are differences. One kind has these black freckles on their faces or covering their gills much like individual fingerprints. Each fish has got a unique pattern.

The ultraviolet patterning is also a secret code. Bigger fish, predators like sharks, can’t see in the ultraviolet range. The damselfish don’t want to attract unwanted attention, so they recognize each other in a kind of undercover way, and meanwhile they all display a yellowish color that blends in fairly well against the coral reef.

Why don’t sharks see in the ultraviolet range?

Choudhury: It’s just the way they’ve evolved. Evolution is always a race. Sharks eat lots of things, so it’s not absolutely critical for them to see individual damselfish. They’ve evolved other survival strategies.

In the end, we have been able to combine worlds and capture the imagery.

You tell an amazing story about this small fish that camouflages itself to deceive a bigger fish. The big fish expects to be groomed by a particular species but this imposter bites it instead! And you managed to capture this fish actually changing color to do its dastardly work.

Geiger: It was a monumental challenge. Those small fish are not terribly hard to find, but they’re very fast, and they dart around. It was really tricky to try to follow one of these fish and catch this one moment of behavior. We spent many, many hours underwater following them with rather large cameras, trying to keep them in the frame.

When you got that fish changing its colors, you must have said “Eureka!”

Geiger: It was fantastic to finally see it happen. When the fish changes color, it happens very quickly. Everything is moving, light is changing, and there isn’t any kind of pattern you can follow to know when they will do it. Sometimes they do it and sometimes they don’t.

There is an amazing sequence showing the mind-boggling display of a magnificent bird of paradise as he’s trying to seduce a mate. Attenborough comments that previous footage usually shows this display from the ground up, where it is easier to put a camera. But the female watches the display from above.

Choudhury: Birds of paradise are a big group that all have amazing displays and plumage. We worked with a camera operator and scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who realized a few years back that the female—for whom this display is intended—watches from above, but was always filmed from the ground, at the eye level of the male bird. We filmed the Magnificent Bird of Paradise from above, from the female view. The results are extraordinary—displays and colors never seen before.

Was your cinematography team responsible for any particular innovation?

Choudhury: The polarization camera is indeed brand new. There were only two in existence when we set out on the series. One had been developed by scientists in North America to detect cancerous tumors. And another scientist in Australia was using it to study damselfish in laboratories, but the cameras weren’t made to go out into the field. So, that was the challenge really. One camera was adapted to film out on mud flats in very difficult terrain. These polarization cameras have to be connected to a laptop. The other camera was used to film fish and mantis shrimp, so you had to get the camera and laptop into underwater housing. All of this was new and I don’t think these kinds of images have been shown before.

What is the main contribution of technology that adds to our understanding and informs your film?

Geiger: Ultraviolet photography has been done for a long time. So has trying to capture polarized light, for example. What hasn’t been done before is combining the two images, getting them at the same time in a quality high enough to put on television, or on a screen, to illustrate what those differences are to the average person. A lot of these cameras have been developed for industry, or for medical uses, where a specific marker is made visible and polarized. We’ve taken these cameras and adapted them for our own purposes.

In the end, we have been able to combine worlds and capture the imagery.

What is it like to work with the legendary Sir Richard Attenborough?

Choudhury: It was very exciting for us to work with him. He was really excited to fulfill a long ambition to do a series on color, particularly at a time when science and technology have become so advanced. He could tell some of the stories that hadn’t been told before about ultraviolet colors and polarization. He’s a man who still has that enthusiasm and passion for anything new, new stories, new signs, new technology, and he, of course, brings something to any project. He just lifts it to a different level and makes the science much more understandable for the audience.

What would you say makes Attenborough so special?

Choudhury: I think David Attenborough really excels when he interacts with an animal—he just has a really natural way of doing that. We were in Costa Rica filming with him in very strenuous conditions. It’s very hot in the rainforests, and we were filming little poison dart frogs and scarlet macaws. These are all wild animals that don’t just come and land on a tree next to you or whatever. But he has such a calm presence and such a natural manner that you just get these magical pieces with him that bring the animal to life.

Mary Ellen Hannibal is the author of Citizen Scientist: Searching for Heroes and Hope in an Age of Extinction, the winner of Stanford’s Knight-Risser Prize in Western Environmental Literature, and a Stanford media fellow.

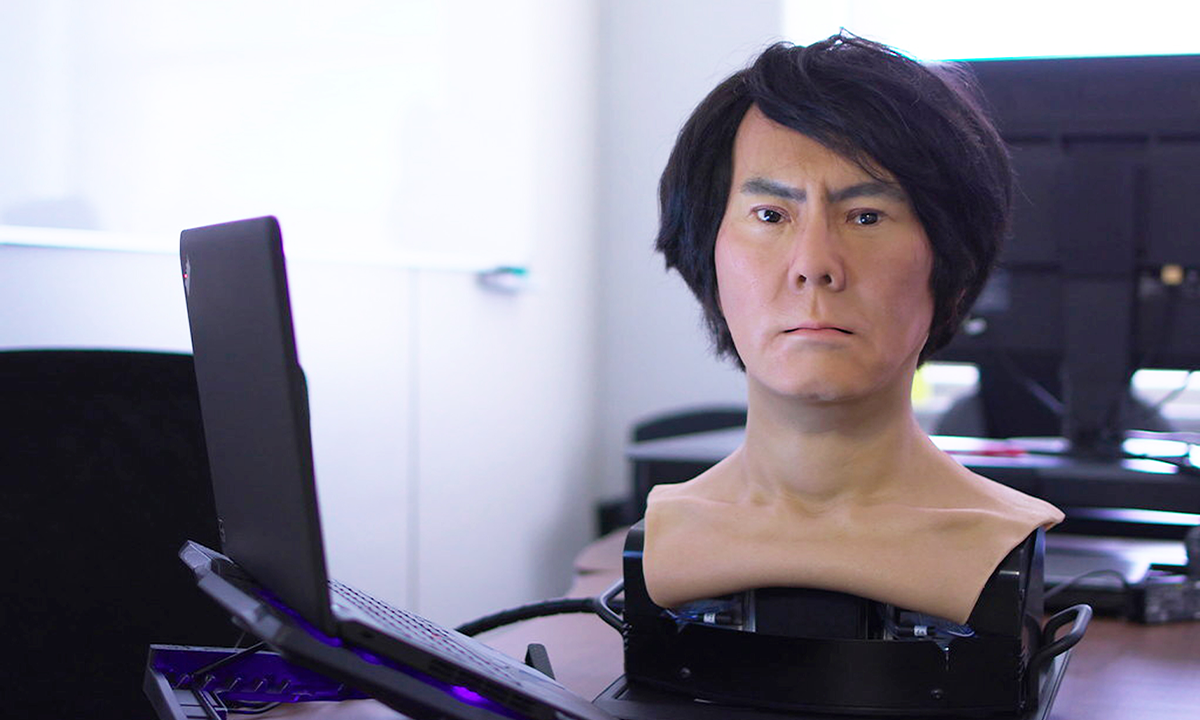

Lead image: Still from David Attenborough’s Life in Color, produced by Humble Bee Films and SeaLight Pictures.