Around 66 million years ago, tragedy struck the dinosaurs when a massive space rock barrelled into what’s now the Yucatán Peninsula in southeast Mexico. This killed off around 75 percent of all the planet’s species, dinos among them.

Scientists have long thought that ammonites—extinct, curly-shelled mollusks related to today’s squids and octopuses—perished in this disaster, known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Some teams had previously proposed that certain ammonites survived, according to fossil finds, but this theory has proven controversial.

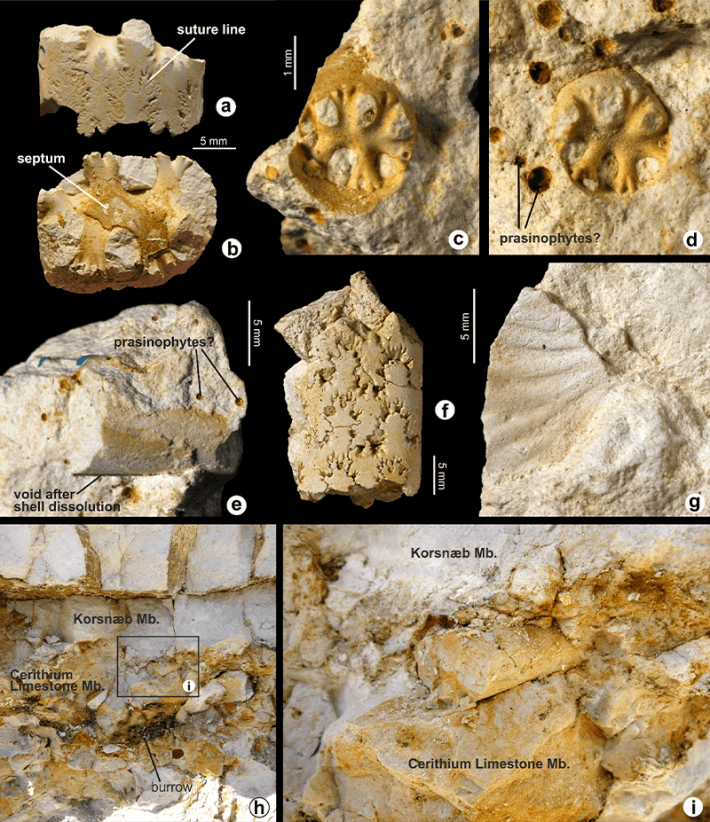

Now, evidence suggests that some of these spiral-shaped species did manage to persist after all. Recent analysis of ammonite fossils dug up around a coastal cliff in Denmark, a site known as Stevns Klint, hints that these cephalopods traversed the sea after the mass extinction event.

This site contains a well-defined rock layer chock-full of fossils that represents the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods. A team of scientists from Europe and the United States inspected ammonite fossils from the earliest chunk of the Paleogene section at the site, which has previously been studied for insights on the creatures that recovered from the asteroid hit in shallow marine environments.

These ammonite remains were previously thought to date back before the extinction event, eroding and landing in a more recent rock layer. But according to microscope analysis of these contentious fossils, the mud within them included tiny spikes from sponges that are commonly found in remnants from the early Paleogene period. They also couldn’t find evidence of tiny moss animals or sea mats that are typically associated with the Cretaceous period, according to a paper recently published in Scientific Reports.

Read more: “The Origin of the Asteroid That Killed the Dinosaurs”

The microscopic evidence aligns with past estimates that ammonites stuck around for nearly 70,000 years after the asteroid impact. This means that the ammonite cold case still begs to be solved—future studies should aim to pin down “what actually killed the last ammonites that lived on Earth,” the authors wrote. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Stefano Puzzuoli / Wikimedia Commons