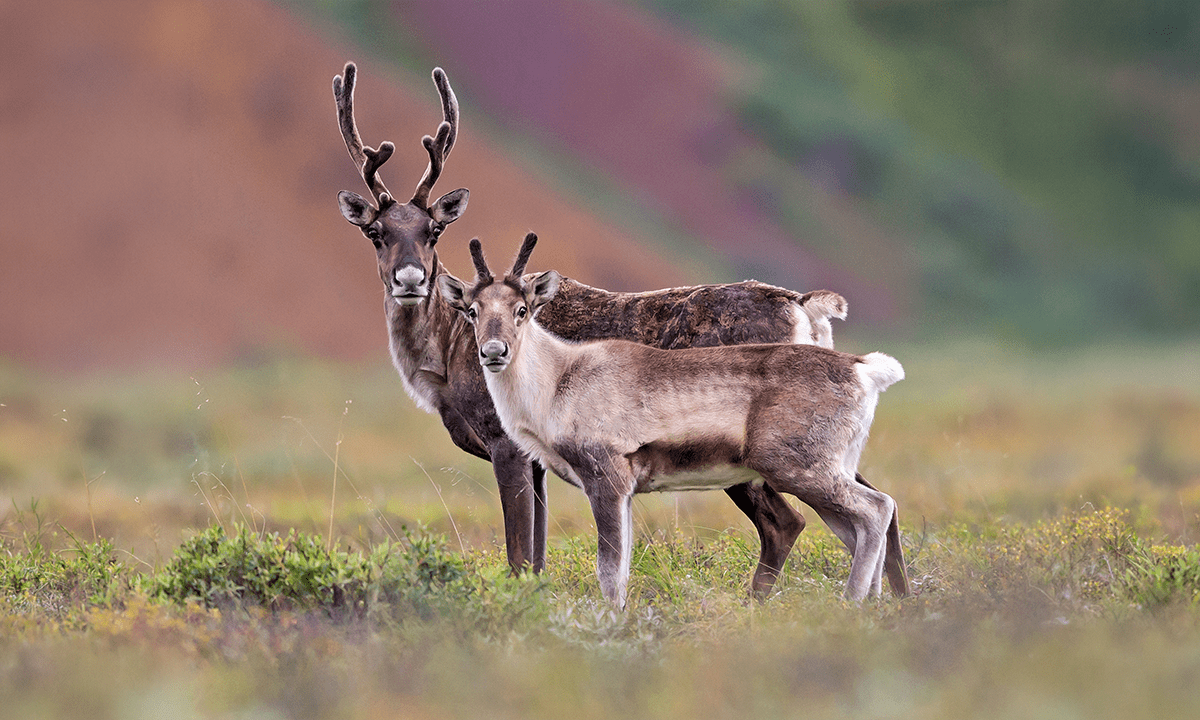

Like humans, some other primates like to huddle in hot springs. Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata), also called “snow monkeys,” famously gather at natural hot springs to soak together for hours. They prefer steaming temperatures of about 106 degrees Fahrenheit that sharply contrast with air temperatures in their wintery mountain habitats.

Humans recognize the warming and stress relief benefits of soaking, but scientists have wondered about the implications for parasite load. On the one hand, hot springs may expose bathers to pathogenic bacteria, such as the Acanthamoeba spp. that cause encephalitis. On the other hand, hot water may kill lice or boost immune systems to better combat pathogens.

A study published in Primates by Kyoto University researchers, led by a wildlife conservation biologist at the Wilder Institute in Canada, studied the parasite loads of macaques at the Jigokudani Monkey Park in Nagano, Japan. Researchers collected fecal samples from 16 adult females (9 bathers and 7 non-bathers) to compare their internal parasite loads. Observations of their nit-picking behavior served as an indicator of external lice loads.

Read more: “How a Hurricane Brought Monkeys Together”

Overall, the abundance of gut parasites, which included protozoans and helminth worms, was similar between bathing and non-bathing macaques. But four types of bacteria (Methanobrevibacter, Granulacatella, Fusobacterium, and Acinetobacter) were substantially more prevalent in the monkeys that chose not to soak. As for lice, whether macaques bathed or not, they picked more nits off their upper bodies than lower bodies. But, for the bathers, this difference was more pronounced, suggesting that the hot water may have driven lice upward.

Basically, while the hot-spring soaking didn’t statistically change the probability of infection with parasites, it did appear to cause shifts in the relative abundance of both internal and external parasites.

“Behavior is often treated as a response to the environment,” explained first author and Kyoto University wildlife biologist Abdullah Langgeng in a statement, “but our results show that this behavior doesn’t just affect thermoregulation or stress: It also alters how macaques interact with parasites and microbes that live on and inside them.”

At least in these natural hot springs, it may be a relief to some of us that communal bathing doesn’t increase disease risk. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: AarenChenPS2 / Shutterstock