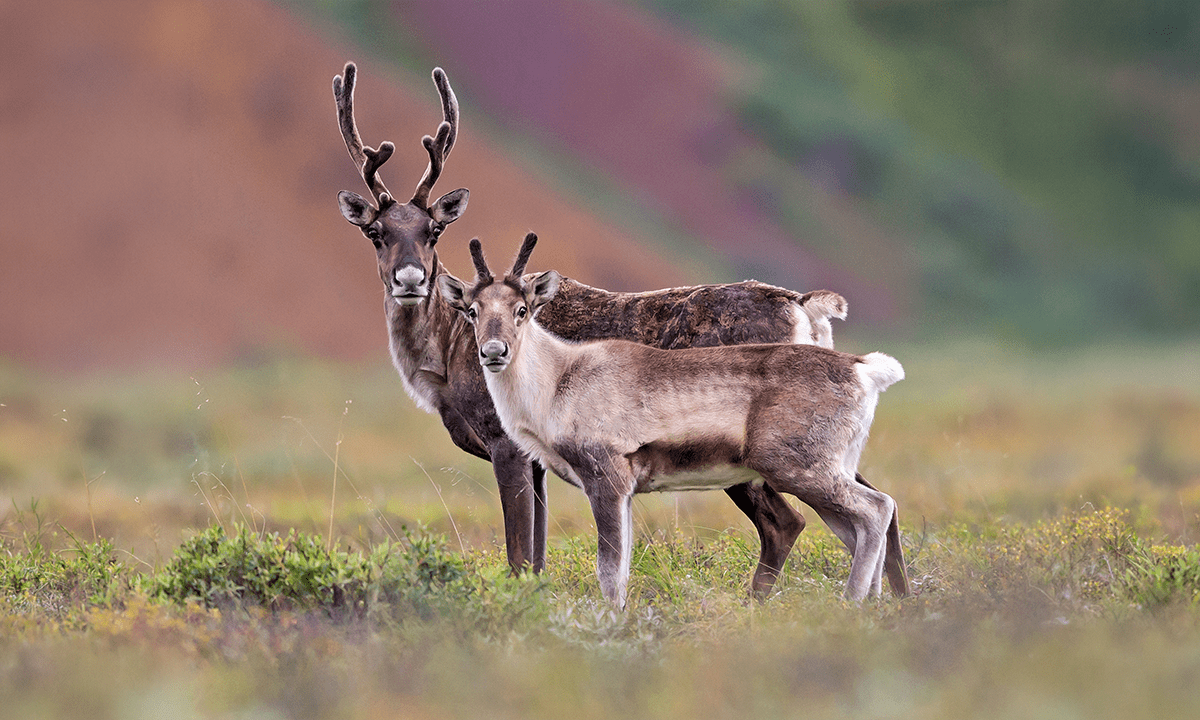

Plant-eating animals need to get crafty to get the salt they crave. Because sodium is relatively rare in nature and plants don’t tend to concentrate salts, herbivores get the stuff wherever and however they can. Elephants in Kenya, for instance, frequent caves to munch salt-rich rocks, and pachyderms in the Congo excavate riverbeds for subterranean sodium deposits. Most African herbivores have found other ways to maximize their sodium intake, gathering at salt pans across the continent or focusing on the saltiest snacks in their habitats.

Now, researchers have suggested that some parts of Africa have relatively few megaherbivores, such as elephants, rhinos, and giraffes, because those areas do not have enough salt to support the massive animals. The international team of scientists published their results today in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Animals need salt to survive: Sodium acts as a molecular pump, shuttling essential components into and waste products out of cells. It aids in the transmission of electrical signals along neurons and regulates water balance on the cellular level and throughout the body.

Read more: “Were These Caves Licked Into Place?”

While carnivores get plenty of sodium from the blood and meat of their prey, herbivores have to scrounge salt from their typically sodium-poor plant diet. Salt deficiencies can be especially problematic for large-bodied herbivores, which need loads of salt to fuel their massive bodies and function properly.

“In Africa, sodium availability varies over a thousandfold in plants,” said study co-author Andrew Abraham, an ecologist at City University of New York, in a statement. “This means that in many areas, wild herbivores simply cannot get enough salt in their diet.”

Abraham and his colleagues compiled high-resolution maps that indicated the distribution of sodium in plants and grasses across sub-Saharan Africa. Then, they overlaid these maps with densities and distributions of sodium in herbivore dung across the same area.

The researchers found an area of West Africa that seemed to lack high numbers of the largest land animals on Earth. This may have been owed, at least in part, to plant sodium scarcity in this area. “West Africa is a very productive region, but there aren’t many megaherbivores there,” said study co-author Chris Doughty, an ecoinformatician at Northern Arizona University. “We think that a lack of sodium, likely combined with other factors such as overhunting and soil infertility, plays an important role in limiting their numbers.”

Across their broad study area, the scientists noted this correlation between areas of salt scarcity to lower numbers of large herbivores.

The findings could have major implications for conservation efforts in Africa and beyond. Humans have shifted natural sodium distributions from activities including drilling boreholes, introducing artificial salt licks, salting roads, and mining, the authors wrote. This might free up more sodium to herbivores, and thus “may enable higher herbivore population densities in certain [sodium]-poor areas,” which could disrupt long-standing ecological dynamics, with effects rippling through these disturbed ecosystems.

Additionally, many areas protected for native species are in sodium-poor landscapes. So large herbivores targeted by conservation efforts may be limited in how much their populations can recover in those ecosystems. This could lead to clashes between these large beasts and the humans that share these areas. “If animals can’t get enough sodium in their natural habitats, they may come into conflict with people on their quest to satisfy their salt hunger,” Abraham added.

It appears that conservation efforts that target the planet’s largest animals should come with a pinch of salt. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Langeweile / Pixabay