On the top of Mount Everest, in the Mariana Trench, in the human placenta, and babies’ feces: Plastics are everywhere. They are built to last, and last they do: A plastic bag can endure for 20 years in the environment, and a disposable diaper, soiled or not, up to 200.

When they do finally break down into microplastics—smaller than 1 micrometer, or about 1/70th the diameter of a human hair—they can become difficult to detect. These microplastics are so ubiquitous in the environment that some scientists think we should track how they cycle through the global oceans, atmosphere, and soil much in the same way we track carbon and phosphorus.

Through soil, wind, and water, they even get into our food: Scientists have found microplastics in beer, honey, salt and most of the proteins we consume—everything from seafood to sirloin steak and even plant-based meat alternatives. We keep looking for plastics, and we keep finding them in new and surprising places. Below, five recent discoveries that expand our knowledge of our plastic footprint.

A liter of bottled water contains around 240,000 detectable plastic fragments.

Clouds: Researchers recently collected 28 samples of liquid from clouds at the top of Mount Tai in eastern China. They found microplastic fibers—from clothing, packaging, or tires—in their samples. Lower altitude clouds contained more particles. The older plastic particles, some of which attract elements like lead, oxygen, and mercury, could lead to more cloud development, according to a paper published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

Rocks: Have you heard of plastistones? That’s the name scientists have given to a new type of sedimentary rock formed when molten plastic from burning trash cools down and fuses with minerals from the environment. These plastitones have now been found in 11 countries on five continents. They can wreak havoc on microbial communities, especially in the ocean, where the rocks may be mistaken for algae. They could also reshape the geological record of our planet.

Bottled water: Scientists recently found that on average, a liter of bottled water contains around 240,000 detectable plastic fragments—10 to 100 times greater than previous estimates. Their research, published in the journal PNAS, focused on the tiniest plastic particles—nanoplastics. These particles can cross into the brain, gut, heart, and through the placenta to babies in utero.

Farm fertilizers: We’re making progress on the circular waste economy by using treated sewage sludge as fertilizer. But that sludge has now been found to be packed with microplastics. A study in the journal Environmental Pollution estimates that the “practice of spreading sludge on agricultural land could potentially make them one of the largest global reservoirs of microplastic pollution.”

Glaciers: You might think of the glaciers of Antarctica as some of the last wild and pristine places on Earth. But scientists recently found plastics there for the first time in the remote Collins glacier on King George Island—probably brought in by gusty winds. Plastics in glaciers and sea ice could increase the rate at which they melt, because plastic absorbs more heat than ice does. “Our results also show that plastic pollution, even if only in small quantities, reaches remote areas with few human settlements,” they write. ![]()

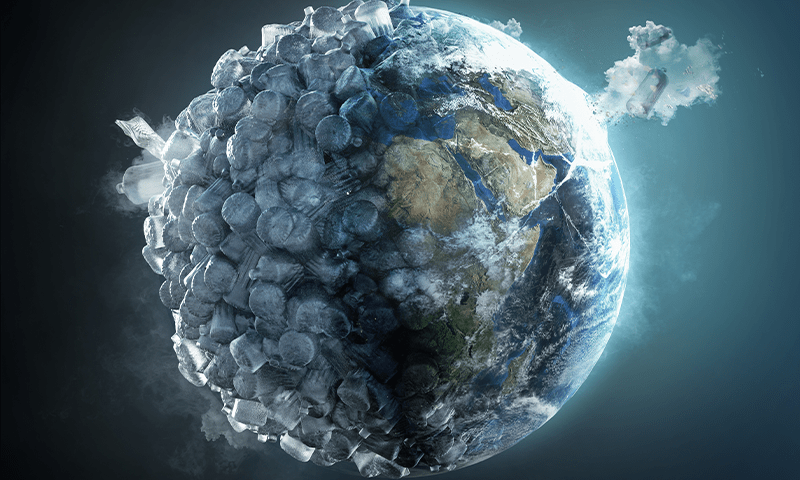

Lead image: m.mphoto / Shutterstock