It was born when the Universe was just 10 human heartbeats old. A small burst of electromagnetic energy known as a photon. A primordial particle of light.

At that time the Universe was a blazing hot mix of ionized hydrogen and helium, a sea of positively charged nuclei and electrons at full boil. This sea was so hot and dense that the photon was constantly scattered, or bounced around between them, never traveling far between. For 380,000 years, the light was scattered as the Universe cooled, until finally ions and electrons slowed down enough to combine into hydrogen and helium. These atoms didn’t scatter the photon much, and so the photon was finally free—free to begin a very long journey.

Although it had cooled significantly by that point, the Universe was still quite hot, about as hot as the surface of a red dwarf star. The photon traveled through the deep red glow of the Universe. As the Universe expanded, it continued to cool, and the red glow faded. Soon the Universe grew dark. There were no stars to generate light, only clouds of hydrogen and helium, and photons hurtling through increasingly empty space.

By that time gravity was beginning to have an effect on the hydrogen and helium, gradually coalescing the gas into galaxy-sized clumps. But gravity works slowly on a cosmic scale, and the formation of galaxies took eons. After about 400 million years, new light appeared, born within the hearts of the first stars. It radiated out when stars began to fuse hydrogen and helium into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen, unleashing enormous power. Soon countless stars and galaxies began to illuminate the Cosmos. From time to time, a star would consume all of its gaseous fuel and explode as a supernova. For a brief period, it would outshine an entire galaxy, and cast gas and dust back far into space.

Still the photon traveled on at its constant speed. It traveled for billions of years, as some stars exploded as supernovae and new stars formed from their remnants of gas and dust. Some of the gas and dust formed into planets and asteroids and comets. Solar systems became common, and a few of their planets happened to form in habitable zones, distances from their stars where liquid water could exist. Not too hot and not to cold. On at least one of these worlds, but perhaps upon millions of them, life appeared.

Still the photon traveled, on and on, for more than 13 billion years. Once, it passed within a few hundred thousand light-years of a galaxy, and the mass of the galaxy deflected the photon, tugging its slightly off of its previous path, an effect known as gravitational lensing. The direction of the photon changed just enough that it began to travel directly toward one rather unremarkable galaxy. A barred spiral galaxy around 100,000 light-years across.

This ancient photon traveled as the first humans walked upon the Earth. It traveled as civilizations rose and fell. It traveled on the day you were born. On and on, year after year. Then one evening, as you were looking up at the night sky, it smashed right into your forehead. And you didn’t notice. You couldn’t possibly have noticed. When the photon began its journey, it was hot and bright, but as it traveled for billions of years, the constant expansion of the universe stretched the wavelength of photon. The stretching made it cool and dim so that it became invisible to human eyes and too weak to feel. Ancient photons like that one strike us all the time, and we never notice.

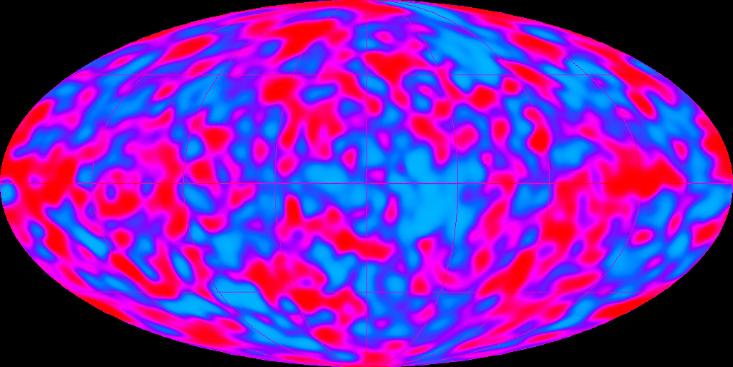

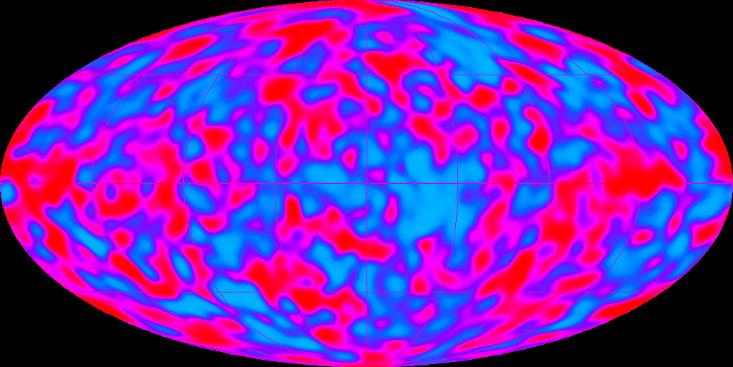

In the 1960s, we did begin to notice. Radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered that the Universe radiates with a faint microwave glow—the photons that have been traveling the universe almost since the Big Bang and are arriving at our solar system now. This glow became known as the cosmic microwave background. In the 1990s a satellite called the Cosmic Background Explorer observed small variations in the temperature of this glow, which confirmed that the Universe began with the Big Bang, a moment energetic enough to have created the glow in the distant past. Over the last decade, new satellites known as WMAP and Planck observed this background in greater detail, and it became clear that the Universe began about 13.8 billion years ago.

Then just this week, a project known as BICEP2 discovered a subtle pattern within the cosmic microwave background. This pattern was formed by gravitational waves that rippled through the cosmos. These waves were caused by a rapid expansion of the Universe known as inflation, which occurred when the Universe was the tiniest fraction of a second old. 13.8 billion years later, we can still see its effect in the ancient glow of microwave light.

The next time you look up into the night sky, you might see light from planets that have traveled for hours to reach you. You will see starlight that has traveled for years, and perhaps centuries. You might even see light from a galaxy that has traveled for millions of years. What you won’t see is the faint glow of the cosmic microwave background, traveling so long that the expansion of space itself has stretched the photons beyond the point where we can see them.

But some of those photons will strike you as you look up in awe. Light from the earliest moment of the Universe, traveling the vastness of space to reach you. From your perspective the light will have traveled for billions of years. And yet, for a photon there is no experience of time. At the speed of light, the journey of a photon occurs in an instant. A journey from the birth of the universe to you.

Brian Koberlein is an astrophysicist and physics professor at Rochester Institute of Technology. He writes about astronomy and astrophysics on his blog One Universe at a Time. You can also find him on Twitter @BrianKoberlein.