When the hip hop artist and music producer DJ Spooky first visited Antarctica in 2007, he was astonished by how fast everything there is changing. Meltwater can be heard trickling at the edges of formerly solid glaciers; the waters echo with the creak and roar of icebergs as they melt. Natural changes on this scale should take millennia. After all, Antarctica’s ice sheet—almost 10 times the volume of its northern rival in Greenland—took millions of years to create. Now it is disappearing at speeds visible on human time scales. DJ Spooky had the impression of “slow motion geological time” being “sped up by human climate change.”

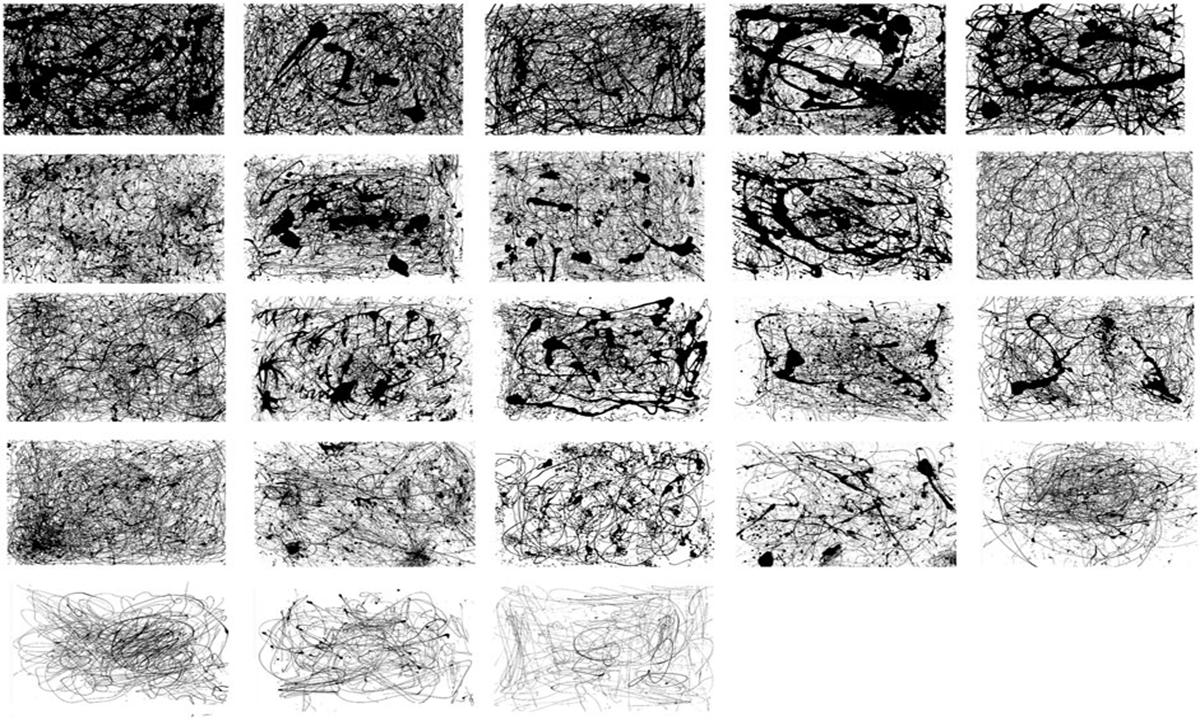

DJ Spooky visited Antarctica to witness at first hand the changes befalling one of our planet’s most sublime places—a landscape that has long seemed beyond human influence. His multimedia work Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica incorporates video and sounds he recorded from the ice and ocean, accompanied by melodic strings that seem to alternate between lament and sharp urgency. He plays with motion—even manipulating how sound itself moves through the room—to bring what he calls an “emotive, kind of immersive quality” to the experience.

In Melville’s poem, the natural world is still overwhelmingly powerful.

Icebergs have also cast their spell on Catherine Walker, a glaciologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. She too has sailed among Antarctic icebergs and been astonished by their formidable beauty and fragility. To study changes in Antarctica, Walker primarily works with numbers: the physics of how icebergs are created and destroyed. But she is also fascinated by their stories. An iceberg is created when a chunk breaks off the edge of a larger ice sheet, such as the one covering Antarctica. Icebergs can be huge—as big as Rhode Island—and seem to have lives of their own.

One of her favorite icebergs “calved” (or broke off) from Antarctica the year she was born. It is large enough to appear on satellite images. “I watch as it goes around the Antarctic continent and shrinks away,” she says. Such stories help her—and others—care about the distant, abstract fate of a place as far away as Antarctica. “This is not an interesting story to tell in a research paper,” Walker admits, but it motivates her work: “I want to see what happens and help tell its story as the climate changes.”

These stunning transformations have their roots in the late 19th century, when the world seemed balanced on a tipping point. The great seafaring writer Herman Melville captured this moment of transition in his poem “The Berg (A Dream).” In reflecting on this poem, DJ Spooky and Walker carry us out to sea, amongst the icebergs of an earlier era—a period before we feared the fragility of Antarctic ice, but after we had begun to fear our own power to change the natural world.

“The Berg” tells the story of a bravely decked-out ship of military design that crashes into an iceberg. When the poem appeared in 1888, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing. The United States and other nations were rapidly urbanizing, once-abundant species were dwindling, and new forms of power—steam, petroleum, electricity—were transforming human life. Today, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses the period from 1850 to 1900 as a baseline to compare today’s post-industrial carbon dioxide levels. Melville had seen many changes already: Even the whales that star in his epic Moby-Dick had been hunted relentlessly—nearly to extinction in the case of some species.

In Melville’s poem, the natural world is still overwhelmingly powerful. The devastating collision that sinks the ship—much like the Titanic would sink 24 years later—hardly budges the iceberg. Yet the energy of human ambition hints at a different future, as explorers venture into even the remotest, most hostile places.

The poem reads like a tongue-twister: It is composed in the style of ancient Anglo-Saxon sagas of exploration, which used heavy alliteration. That very difficulty seems to capture Melville’s cultural moment, when the age-old drive for conquest met contemporary sensibilities: awe, wonder, even a secret desire that nature win out in the end.

When he wrote this poem, Melville may have had in mind an image of the sloop-of-war USS Peacock confronting Antarctic ice in 1840. The Peacock had seen service in the War of 1812 and fought pirates in the Caribbean before she sailed to Antarctica as part of the United States Exploring Expedition, commanded by Naval Lieutenant Charles Wilkes.

An engraving from the expedition, with which Melville was familiar, illustrates a terrifying episode in which the Peacock was nearly crushed by icebergs. The icy cliff in the engraving looms over the proud ship, with the “dead indifference of walls” Melville describes. The Peacock had gotten trapped in a field of ice, which smashed into and disabled the rudder, rendering the ship almost impossible to steer; a tremendous collision with an iceberg subsequently destroyed parts of the ship’s stern. As the ship rebounded, “an impending mass of ice and snow fell in her wake.” Wilkes tells us that, “had this fallen only a few seconds earlier, it must have crushed the vessel to atoms.”

The Peacock was miraculously saved by an opening in the ice. Melville’s “ship of martial build” is not so lucky. The iceberg in the poem, “atilt impending,” drops “huge ice-cubes … / Sullen, in tons that crashed the deck.” At the time, Antarctic ice represented the immense power of nature: sublime obstacles that stood in the way of industry’s expanding energy. Antarctica seemed like the one place on Earth that humans were simply not meant to go. One explorer complained in 1832 that too many of his peers had fallen for:

a superstitious notion that an attempt to reach the South Pole was a presumptuous intrusion on the awful confines of nature,—an unlawful and sacrilegious prying into the secrets of the great Creator.

To fearful navigators, Antarctic ice had issued a divine warning: “Thus far shalt thou come, but no farther; and here shall thy proud course be stayed.”

In that era, icebergs truly seemed to be “ice mountains.” Like mountains, these bergs seemed immovable and unchangeable. They appealed to artists and writers like Melville, who were fascinated by physical and psychological extremes. In the 19th century, strong passions were in vogue, as were the sublimities of extreme landscapes. The painter Frederic Church took a rowboat perilously close to several icy giants in the Arctic to paint “The Icebergs.” Two years after the painting was first exhibited in 1861, Church added the broken mast of a ship to suggest humanity’s helplessness against these seemingly unconquerable natural wonders.

Both DJ Spooky and Walker say the Antarctic icebergs they’ve seen up close are as impressive and frightening as in Melville or Church’s day. Yet, to both the artist and scientist, it is not only Melville’s ship that seems doomed. The ice, as imposing as it feels, is, at its core, but an impermanent, “ghostly thing,” Walker says. As Melville writes, even the “hard berg” is “adrift dissolving, bound for death.” In 1888, climate change and global warming were still ideas far in the future, yet already Melville had an eye on how the tables might turn. ![]()

Lead image: Frederic Church, "The Icebergs" (1863). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.