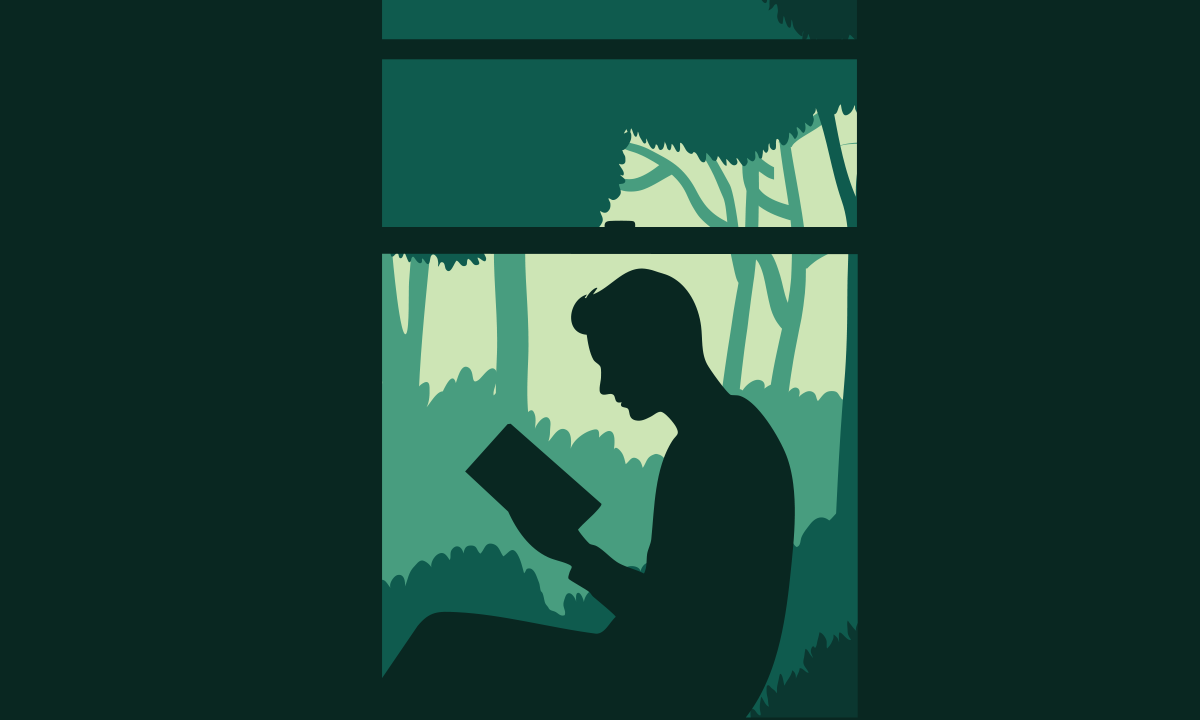

Curled up in a wooden chair with an embroidered quilt over her head, 8-year-old Carol Frischmann held an old-fashioned flashlight to her favorite book. The quilt, white with a rose in each corner, was the magical force that transported her from the South Carolina world she lived in and into the one she craved to explore. The walls disappeared, the farmland outside her window faded and the ocean came inside. Underneath the quilt, she sailed through the wondrous oceanic vastness in a powerful submarine, and the mysterious sea creatures came and stared her in the eye.

“What seemed totally magnificent was that a character could get into a vehicle and see a world no one has seen before,” says Frischmann, 59, who now lives in Portland, Oregon—by the water. “And from that day on, I wanted to do that—I wanted to know about everything that lived under the sea.”

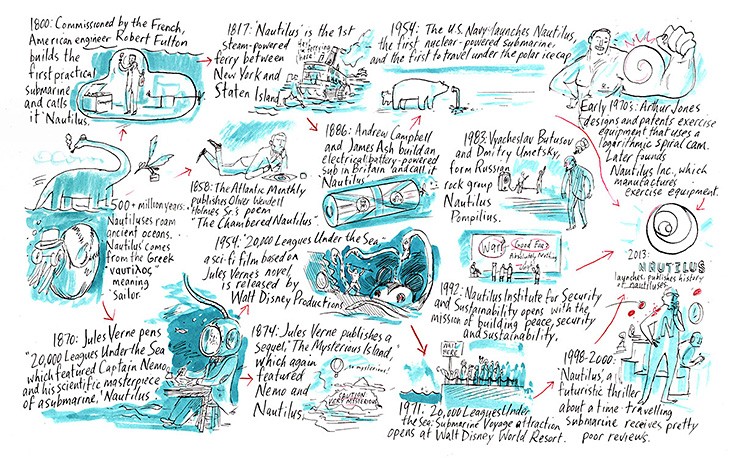

Frischmann’s scientific interests were shaped by 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the 1870 novel by Jules Verne that featured an underwater ship called the Nautilus, which became a worldwide symbol of science, fantasy, and exploration. When she grew up, Frischmann embarked on her own marine expeditions, diving in Belize, Cayman Islands, and Trinidad and Tobago. With a degree in science education from Duke University, she authored several books about pets and exotic animals for the Animal Planet Pet Care Library and Tropical Fish Hobbyist magazine. Alaska, she says, is her next diving destination.

Today, when nonfiction and science books seem to rule with readers and dominate dinner conversations, it’s interesting to recall an age when fiction—adventure stories—absorbed the leading science of the day and shaped the culture around it. Verne’s classic speaks to the wonder in both fiction and science and reminds us that connection is far from lost. For what may be most remarkable about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is that it remains a vehicle of wonder and continues to inspire new generations of educators, innovators and writers around the world. Translated into more than 30 languages, the novel in its e-book incarnation continues to hover around the top of Barnes & Noble’s High Tech and Hard Science Fiction bestseller list.

The mother tongues of today’s readers span from Russian to Turkish and from Greek to Farsi, as they follow Verne’s characters through the inner workings of his vessel and the mysteries of the aquatic life, discovering their own passions. Some of his readers chose to study marine biology, some learned to build ships, and others became engineers and artists who drew inspiration from technology and fiction. “The book was so vivid that you could easily believe the technology and the amazing observations were science fact, not fiction,” says Adrienne Klein, a New York-based visual artist, whose works find their origin in science topics. Her exhibits, which have depicted human ability to see color and the circulation of fluids in the body, have appeared in more than 50 art shows in the United States and Europe. A native English speaker, she read the original text years ago when her high school French teacher assigned the book as required reading. “It is remarkable how Verne predated the development of technology,” she says.

Verne was writing at a very exciting time in history. “Science, engineering, and literature were coming together in the ways that never happened before,” says Rosalind Williams, who studies the history of fiction and technology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Science had been an aristocratic and philosophical pursuit of the societal elite. On the contrary, engineering was the vocation of the lower class, of the people who, covered in sweat and soot, built and operated greasy, hazardous machinery in hot, smoky shops. By the end of the 19th century, the two realms met, sparking a burst of industrial novelties. “When he lived in Paris, Verne was very active in what we would now call popular science clubs,” Williams says; with his vision, science made its entry into the imaginative literature. One of the novel’s first readers, engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, who built the Suez Canal, was so impressed by the book that he recommended Verne for the French Legion of Honor, the nation’s highest decoration.

In the book, Professor Pierre Aronnax embarks on a pursuit of a mysterious marine creature that attacks and sinks ships. Instead of a sea monster, Aronnax and his two companions discover an iron, man-made one—an electric submarine built by genius Captain Nemo, a character as mysterious as the technology he had devised. An amicable vigilante who fights imperialism and aids rebels all over the world, Nemo would probably earn the title of a radical extremist today. “Captain Nemo is a terrorist,” Williams says. “But Nemo is also a hero.” (Only in the novel’s sequel, The Mysterious Island, did the readers learn his real identity: an Indian prince who lost his family and kingdom to the British, Nemo built the Nautilus and abandoned the world above to devote himself to research.) Treating the trio as royal captives, Nemo takes them along on his scientific expeditions, from gathering lost treasures on the oceanic floor to being trapped underneath an iceberg to fighting a giant squid. For generations of readers, these insights and adventures became footpaths into their future scholarly pursuits.

Amid the hot and humid Panama summers, 11-year-old Eva Aguiler followed the journey of the Nautilus in Spanish, in the bedroom she shared with her brother and sister. The oldest of the three, she played the part of Nemo as she led her barefoot crew up their bunk beds, climbing up high to escape the scary sea beasts. “It was one of the first books I read, and I became a reader after that,” she recalls. Originally set on studying engineering, she discovered she had a talent for writing—“because of all the books I read in my teenage years.” Now a 40-year-old resident of Manchester, England, she covers science and technology in the developing world for SciDev.net, a nonprofit organization based in London.

Bahar Gholipour, who sailed the Nautilus in her landlocked city of Tehran in a Farsi translation when she was 10, is now finishing her graduate studies in science writing at Stony Brook University, after earning a degree in biology. She recalls that she kept re-reading the novel until her parents grew worried that she was falling behind on schoolwork. “I argued with them that I learned a lot from the book, including things we didn’t talk about in school,” she says. “I learned what a compass was. I learned about the sea animals and that the oceans were connected. I kept going to my parents asking questions—like what is a league?” (A league is a unit of length used by the 18th-century mariners, which equals three nautical miles or about 18,200 feet.) Anthony Mainsfield of Melbourne used to imagine himself as Nemo when he was a kid. He built his first canoe at 10 years old—although with some help from his brother-in-law—and became a marine engineer when he grew up.

Some Nautilus fans went beyond impersonating their favorite characters. Matthew DuPlessie, a 35-year-old designer and engineer, recreated the story of the Nautilus and Nemo in his home state of Massachusetts—literally. He built a 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea immersion adventure attraction—a cross between a science museum and a mini-amusement park where visitors “board” the ship to join Nemo in his scientific quests. In its Nautilus-themed chambers connected by heavy steel doors and illuminated by dim lights, they trace Nemo’s voyages on a map, crank his dynamo to generate electricity for the diving bell, and restart the ship by configuring a wall of gears.

While Verne helped inspire sci-fi, historians say he vehemently opposed the science writer’s title and described his novels as “geographic romances” or extraordinary voyages. “The term science fiction sits uneasily on Verne’s shoulders, if only because the term was invented long after he was dead,” says William Butcher, who studies Verne’s life and work. Williams calls Verne “a prophet of the needs of technology and imagination for each other.” So does Dimitrios Angelopoulos, 44, a naval engineer and a retired Hellenic Navy submarine commander in Athens, Greece. The book was his “first introduction to the underwater world,” and he re-read it after graduating from the naval academy at 25—with a critical eye. “I read more carefully the places that described the submarine propulsion plant, the electrical plant, and I realized they were close to what we have in conventional submarines,” he recalls. Even modern-day procedures to surface match those described by Verne, he says. Angelopoulos was on his 25-day underwater voyage from Greece to Germany and passing the Strait of Gibraltar, where contemporary mariners use the natural water current to boost their speed, when he realized that Nemo did exactly the same trick in the story. “It’s not so easy to imagine that a submariner could use that strait to move faster,” Angelopoulos says. There were no electronic systems to measure the current’s flow when Verne wrote the novel, he points out. “It’s amazing how he saw the future.”

Once Verne skillfully married emerging science with fictional adventures, other creative souls followed suit. Science and fiction evolved around each other, says David Seed, who studies science fiction at the University of Liverpool. “You could say that at any given moment scientists are pursuing projects which seem likely to bear fruit and science fiction writers are drawing on the same cultural pool,” he says, citing numerous examples. Inspired by his favorite childhood novel, Tom Swift and His Electric Rifle, NASA scientist John Cover invented his own electric gun: TASER, an acronym for Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle. Several sci-fi authors toyed around with an idea of a deadly ray, capable of instant destruction. First, the imaginary Martians used it in H.G. Wells’s The War of The Worlds. Then it reappeared as a particle beam in Arthur C. Clarke’s Earthlight and Larry Niven’s Neutron Star—and finally was considered as a laser system for Strategic Defense Initiative during the Cold War. “Indeed, many of the technicians working on the project were themselves keen readers of science fiction and therefore familiar with the ray weapon,” Seed says.

Today, as science continues to weave its way into contemporary life, Verne, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, continue to sail along.

It was the cold winters of the Cold War when 9-year-old Vitaly Artyukhov nestled on his father’s lap in their Leningrad apartment—leafing through the pages of their favorite book. His edition of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was antique. Published in 1918, the manuscript was printed in the pre-revolutionary Cyrillic, the pages full of primeval letters. The old-fashioned engravings, each protectively covered with a crinkly, semi-transparent paper leaf, brought the story to life. But the most precious part was his father’s insights into the ship. Artyukhov–senior worked at Leningrad’s secret research center, Aurora, where submarines were dreamed up, assembled and launched. As they studied the vintage drawings, he explained to Vitaly how one operated a submersible for real.

“I could just imagine myself in there,” says Artyukhov, now a 40-year-old information technology specialist and scuba diver. “I fell in love with all things sea. I gathered shells and brought them home. I was fascinated with the idea of sunken ships full of lost treasure abandoned on the oceanic floor. It was so far gone yet so easily within reach if you happen to float by in the Nautilus.”

He was forced to abandon his own treasure when he left for New York—the historic manuscript had to remain in Russia. One of the first books he bought in his new country was the English version of his favorite novel, a leather-bound, gold-imprinted edition he still owns.

He was in mid-sentence when he suddenly paused and thought for a second—and then a smile of anticipation lit his face. “That reminds me,” he said. “My two sons are now about that same age that I was when my father read me the book. I have to go find it. It’s my turn to do it.”

Born to a family of scientists, Lina Zeldovich grew up listening to bedtime stories about volcanos and black holes. Now a science editor at Nautilus, she writes about science, technology, and health, striving to entertain her readers just as much.