Astronomers have long noticed an invisible elephant in the room—so-called dark matter, which seems heavier than all the visible stars, gas, and dust in the cosmos by a ratio of 6-to-1.

Though no one knows what dark matter actually is, its presence has been inferred from its gravitational influence on ordinary matter in galaxy after galaxy—until now. Astronomers have found a galaxy that appears to be free of dark matter. The claim, reported today in the journal Nature, throws accepted wisdom about galaxy formation into question, and, if confirmed, may help elucidate dark matter’s true nature.

“It really is quite uncomfortable. It shouldn’t exist; it shouldn’t be real,” Marla Geha, an astronomer at Yale University who was not part of the discovery team, said of the strange galaxy. “Yet if you look at the data, that’s the conclusion you’re drawn to.”

Galaxy NGC 1052–DF2, a half-transparent smear of light 65 million light-years away in the constellation Cetus, hosts some 200 million suns’ worth of stars, and negligible amounts of gas and dust. And that’s it. According to the new study by Yale astronomer Pieter van Dokkum and colleagues, the galaxy’s visible matter accounts for its entire mass, a commonsense conclusion that turns out to be deeply strange.

In theories of galaxy formation, heavy clumps of dark matter first attract luminous stuff to them, seeding new galaxies and creating a kind of skeleton for the entire visible universe to hang on. Observations back up this picture. Galaxies around the size of the Milky Way, for example, seem to be nestled inside clouds of dark matter about 30 times heavier than all their stars combined. NGC 1052–DF2, a smaller galaxy, should have 400 times more dark matter than stars, based on observations of dozens of comparable objects. Instead, the new paper suggests, what you see in NGC 1052–DF2 is what you get.

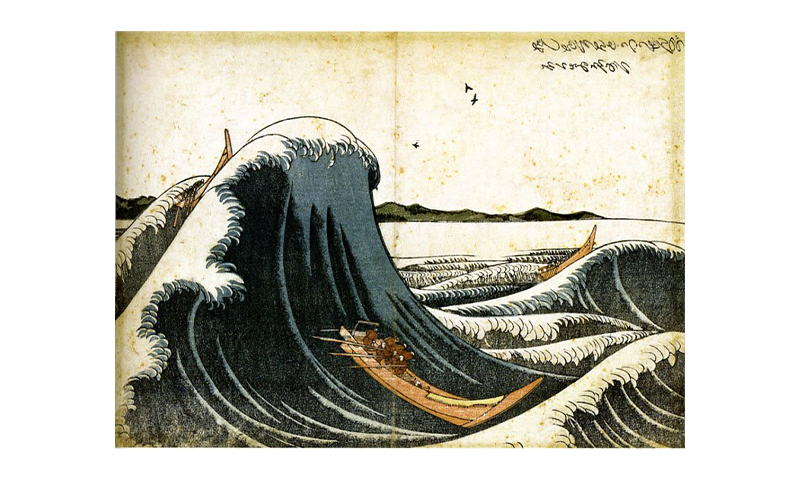

Astronomers first discovered the galaxy in 2000 as a smudge on old photographic plates. But more detailed observations by the Dragonfly Telephoto Array, a DIY-style observatory cobbled together from Canon camera lenses to study faint, extended objects in the sky, caught van Dokkum and his team’s interest. Closer study using the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Keck Observatory in Hawaii revealed a swarm of bright points.

The researchers believe that the points are probably globular clusters, tight balls of stars often found in the outer reaches of galaxies. The ones in NGC 1052–DF2 are mysterious in and of themselves: Many are comparable in brightness to Omega Centauri, the single brightest globular cluster in the Milky Way. By measuring their motions, the astronomers could calculate the mass of material enclosed inside their orbits. They found that dark matter is either very sparse or isn’t there at all.

Parsing what that means isn’t easy, but it does lead to one clear, if counterintuitive, conclusion, the team argues: “Alternatives to dark matter have trouble with this object,” van Dokkum said.

Theories like modified Newtonian dynamics and a new idea called emergent gravity propose that there is no dark matter. Instead of galaxies being filled with mysterious invisible stuff, these theories postulate, gravity works differently than expected on galactic scales, in a way that only mimics the presence of dark matter. But if that’s true, van Dokkum explained, then every galaxy should obey these different laws of gravity and look as if it contains dark matter, with no exceptions.

Theories that challenge dark matter’s existence will need to explain away the new claim about galaxy NGC 1052–DF2 to survive.

But if dark matter is real, physicists still have to explain how the stars of NGC 1052–DF2 got separated from it. The galaxy is on one end of two extremes, the other anchored by Dragonfly 44, another strange galaxy discovered by the same team in 2016. While NGC 1052–DF2 appears to have no dark matter, Dragonfly 44 seems to have much more dark matter relative to visible matter than astronomers expect. Both discoveries challenge normal galaxy scaling relations and call for new theories about how galaxies form. “It’s a pretty fun time in the world of galaxy physics,” said Annika Peter, an astronomer at Ohio State University who was not part of the research team.

Most paths to explaining NGC 1052–DF2’s formation implicate its galactic neighbors. “When I saw this, I was like, ‘Well, I bet this object is in a group environment,’” Peter said. She explained that the larger gravitational field from adjacent galaxies could have pulled dark matter away from it, yanking the tablecloth out from under the stars while keeping place settings intact.

Van Dokkum and colleagues have additional ideas. For example, when two galaxies merge, streams of gas can collide, while the dark matter is thought to pass through without interacting. This would allow the gas to form stars away from clumps of dark matter. However, this galaxy doesn’t seem to have the tail-like features that typically accompany this process. Of the current theories, van Dokkum says, “I think they all have problems.”

The team is now proposing additional observations of NGC 1052–DF2, including with the upcoming, albeit oft-delayed, James Webb Space Telescope. One priority will be to measure the galaxy’s mass by looking at the orbits of its stars, not just the motions of the bright globular clusters.

The larger astrophysics community will be paying attention. “It’s very hard to argue against the data,” says Geha. “But I personally want a lot more study of this object before I’m ready to be fully convinced.”

Lead image: The multi-lensed Dragonfly telescope in New Mexico has triggered a hunt for dim galaxies in our cosmic neighborhood. Credit: P. van Dokkum