In 1979, renowned evolutionary biologists Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin published “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm,” a relatively short treatise pushing back on what they saw as a disconcerting trend in their field.

Evolutionary biologists, the two wrote, had become enamored with atomizing organisms into discrete traits and telling “just-so stories” about how these individual aspects had become optimized by natural selection to their ideal form.

To illustrate the fallacy of this mode of thinking (what they called “the adaptationist’s programme”), they used the example of “spandrels” in Venice’s St. Mark’s Cathedral. A “spandrel” is the curved triangular space between two arches at right angles to each other, and in St. Mark’s they’re decorated with detailed mosaics.

It would be wrong to say the spandrels were created for the purpose of displaying mosaics, Gould and Lewontin explained. Instead, they were architectural byproducts of arch construction, decorated after the fact. And just as spandrels are byproducts of the constraints of architectural space, many biological traits are byproducts of the constraints of physical and developmental processes, Gould and Lewontin argued.

Since publication of their paper, “spandrel” has become shorthand among evolutionary biologists for an incidental trait, or result of a byproduct of evolution. Now, a new study published in PLOS One is investigating the potential spandrelhood of a human trait: the chin.

Read more: “What Made Early Humans Smart”

Absent from other primates—and even Denisovans and Neanderthals—the bony, protruding chin is a uniquely human characteristic and often used to identify members of our species in the fossil record. As such, it’s tempting to indulge in another uniquely human trait (storytelling) and come up with a reason it was honed by natural selection. Among others, supporting the lower jaw to facilitate chewing or acting as a secondary sexual characteristic to advertise maturity to mates, are two such stories.

To investigate theories of the evolution of the chin, researchers from the University of Buffalo examined gene sequences involved in the development of the head and jaw for evidence of evolution. Specifically, the team looked at whether sequences involved in producing the chin itself were subject to direct selection, whether they arose neutrally due to genetic drift, or whether they were merely a byproduct of evolution acting upon other traits (a spandrel). They found that the evidence pointed toward the chin being a spandrel.

“The chin evolved largely by accident and not through direct selection, but as an evolutionary by-product resulting from direct selection on other parts of the skull,” study author Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel said in a statement.

The traits natural selection was most likely acting on included reduced anterior dental size and other cranial changes related to the evolution of bipedalism, the authors clarified.

“While we do find some evidence of direct selection on parts of the human skull, we find that traits specific to the chin region better fit the spandrel model,” von Cramon-Taubadel explained. “The changes since our last common ancestor with chimpanzee are not because of natural selection on the chin itself but on selection of other parts of the jaw and skull.”

It’s an important reminder that traits should be considered within their context, and that not all differences between species are a result of an all-powerful force of natural selection.

“Generating empirical evidence against that line of reasoning is an important goal of this study and biological anthropology in general,” von Cramon-Taubadel said. “The findings underscore the importance of assessing the evolution of physical characteristics with trait integration in mind.”

Something to stroke your chin and think about. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

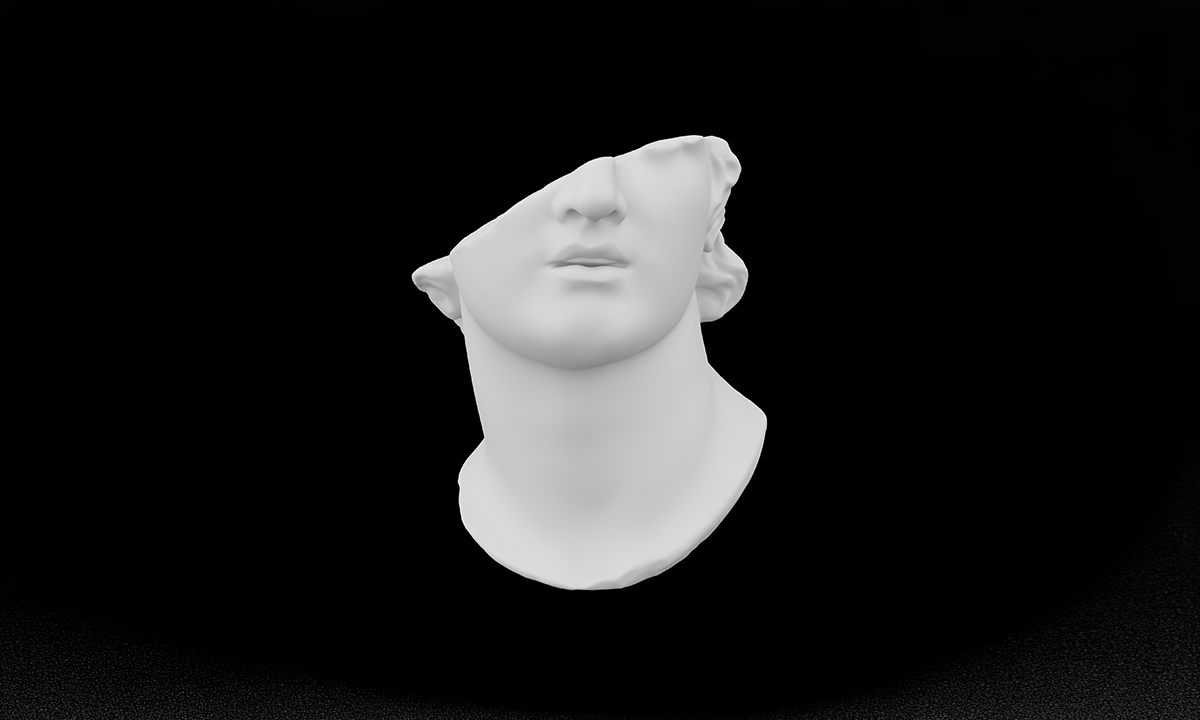

Lead image: cybermagician / Shutterstock