Sleep is risky. When you doze off, your defenses are down, making you an easy mark for predators and other threats. And yet, the majority of living things do it, including most animals, insects and even many plants.

Sleep has many documented benefits, of course: saving energy, repairing the brain, laying down the tracks of memory. But its original function has been harder to pinpoint. Why did it first evolve? It’s a mystery scientists have been trying to solve for decades.

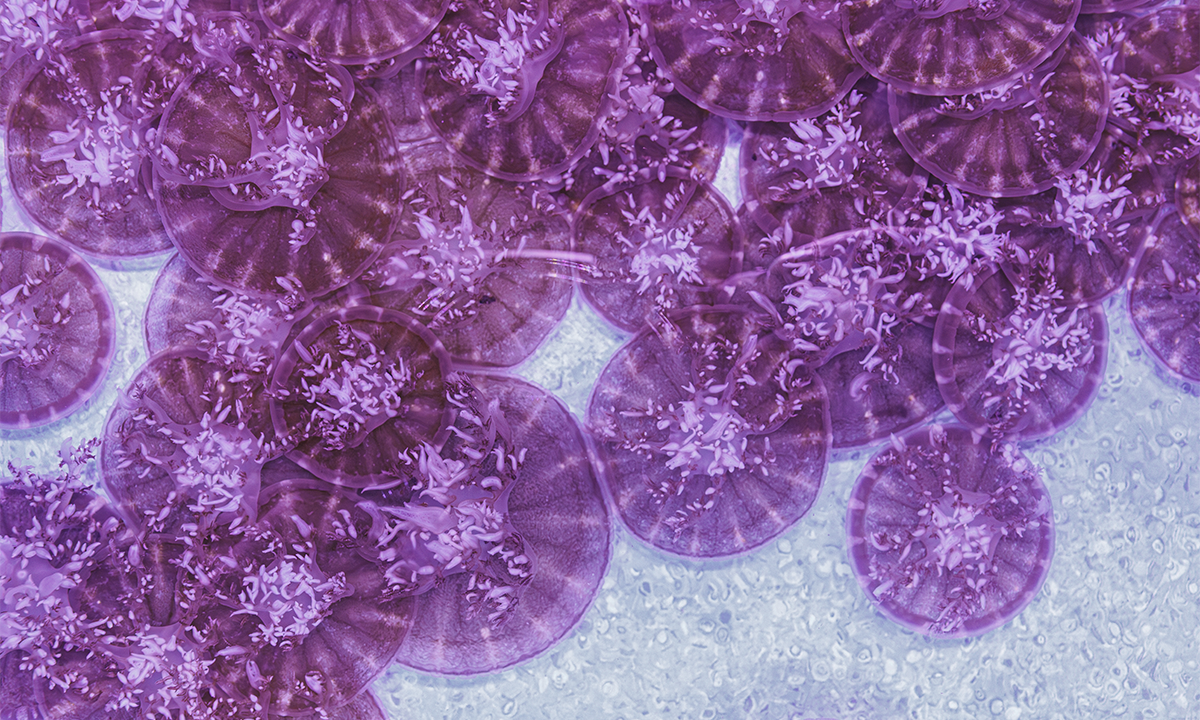

Recently, a team of Israeli scientists decided to plumb the ocean in search of an answer, placing two ancient sea creatures in their sights: the lyrically named upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda) and the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis). Jellyfish and sea anemone are among the oldest animals to have evolved on Earth, belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, whose fossil record dates back to the Precambrian period, some 580 million years ago.

Publishing their findings in the journal Nature Communications, the scientists report that these early creatures need about as much shut-eye as humans do and that sleep may have first emerged as a means of protecting vulnerable neural tissue from the havoc wreaked by the daily grind.

Read more: “Dreaming Is Like Taking LSD”

Scientists already knew that the pair of shallow coastal ocean dwellers keep very different schedules of downtime: The jellyfish sleeps at night, with occasional naps during the day, while the latter is most active in the crepuscular hours, around dusk and dawn. But little was known about their specific sleep habits.

The starlet sea anemone is a tiny burrowing creature that’s mostly translucent, with frilly, colorful tentacles, while the upside-down jellyfish rests belly down on the seafloor, its arms branching overhead like an underwater flower. These animals are so simple that they lack a brain, instead relying on networks of neurons known as neural nets to help coordinate their activities.

First, the Israeli scientists had to establish what counts as sleep for each creature. A jellyfish’s tentacles never stop pulsing, so how do you know when it’s dozing? Looking for quieted pulsing over a sustained period and slowed reaction times to light, they noted that sleep in the jellyfish could be described as under 37 pulses per minute for a period of 3 minutes. For the starlet sea anemone, they used an infrared camera and a light stimulus to identify the dividing line between snoozing and arousal, determining that these animals are sleeping when they’ve been sluggish for 8 minutes and show relative indifference to both light and food.

Using these definitions, the scientists reported that both creatures slept about a third of the day—roughly 8 hours in human terms—in their natural habitats, and that the sleep schedules they kept responded heavily to sleep deprivation, environmental light, and circadian rhythms. Feeding the creatures melatonin—a natural hormone involved in sleep regulation, whose production is influenced by light—led to increased sleep during times when each would normally have been more active, but had little impact on their activity during normal rest phases. It also reduced DNA damage in both species during times of the day when they were normally alert.

The scientists measured DNA damage in the two creatures under different conditions as well and found that it climbed when they were awake and was amplified when they were sleep deprived, but declined when they were asleep and following “recovery” sleep.

Most surprising, they found that DNA damage pushed the creatures to sleep more. In both the jellyfish and the sea anemone, the scientists induced damage by exposing them to certain chemicals and frequencies of light. Then, they recorded the sequences of events that followed: First, additional DNA damage accumulated, then the creatures slept for longer, after which the DNA damage decreased. The relationship appeared to work both ways: More DNA damage led to more sleep, and more sleep reduced DNA damage.

The findings suggest that sleep may have arrived on the scene to allow living things to survive the ravages of time. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Minakryn Ruslan / Shutterstock