Over the past 5,000 years, tattoos have served as symbols of identity and life experiences, among other traditions—they’ve even been used to treat ailments including arthritis. Scientists have unearthed evidence of tattoos on human remains from more than 50 archeological sites around the world, from ancient Peru to China. These include locations in the Nile River Valley in northeastern Africa, which the Nubian people have called home for millennia.

Researchers have studied ancient Nubian tattoos since the 19th century, but more recent technologies that capture images in wavelengths invisible to the naked eye have illuminated intriguing new details from these markings. Now, researchers based in the United States and United Kingdom have harnessed these tools and traced how the rise of Christianity in the Nile River Valley influenced tattooing practices by the seventh century A.D.

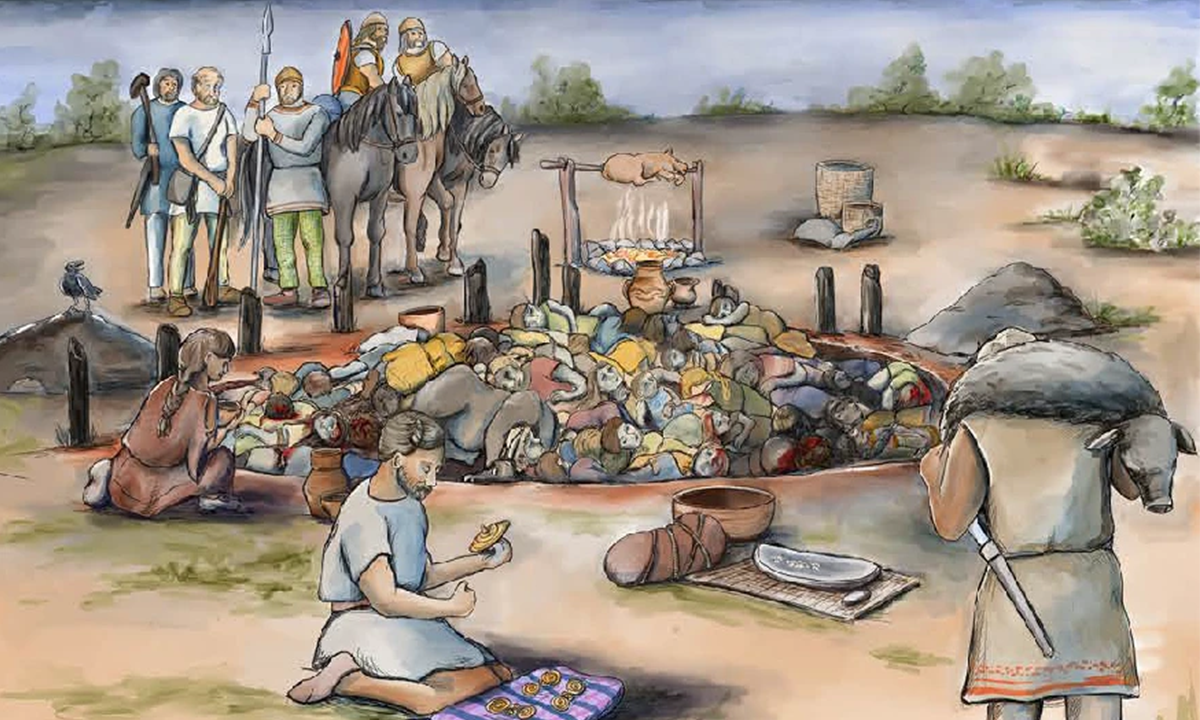

The team surveyed 1,048 samples of human remains spanning 350 B.C. to 1400 A.D. from three sites located in the north of modern-day Sudan. At one site, known as Kulubnarti, Christian-era remains mostly from 650 to 1000 A.D. had “remarkable skin preservation” that the authors wrote “allows a more detailed determination of the significance and ubiquity of tattoo practices,” according to a paper published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Kulubnarti sat near what’s now the Egyptian border and served as a genetic and cultural melting pot.

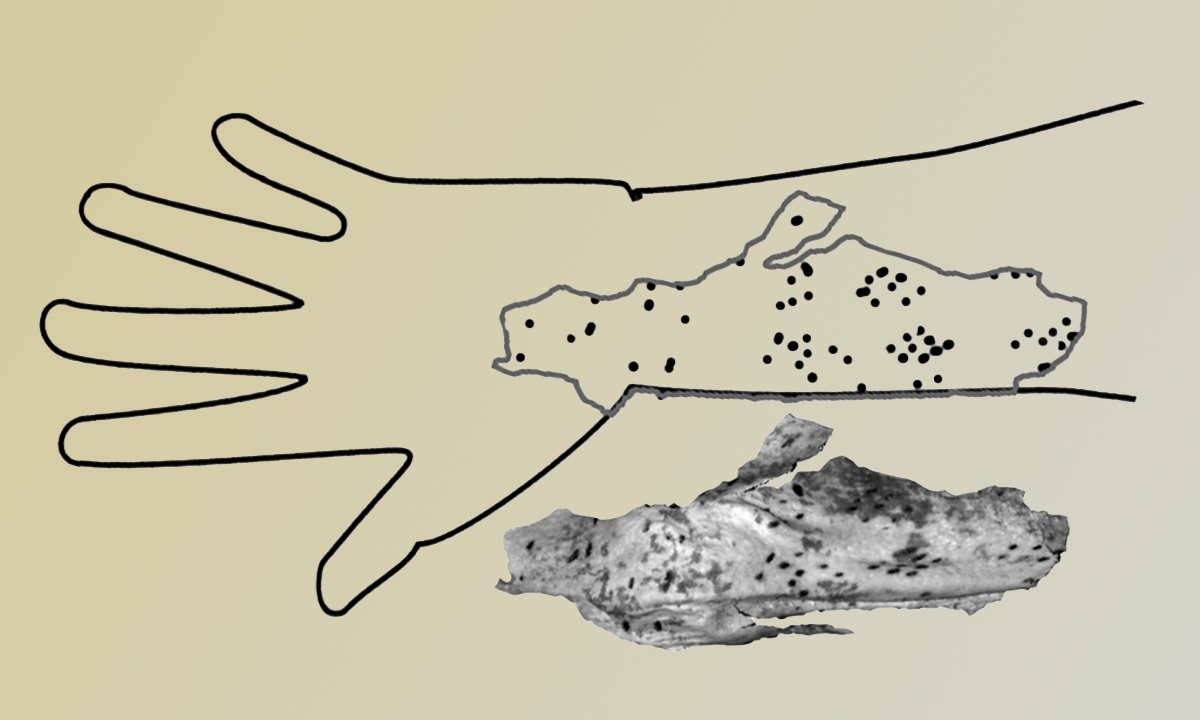

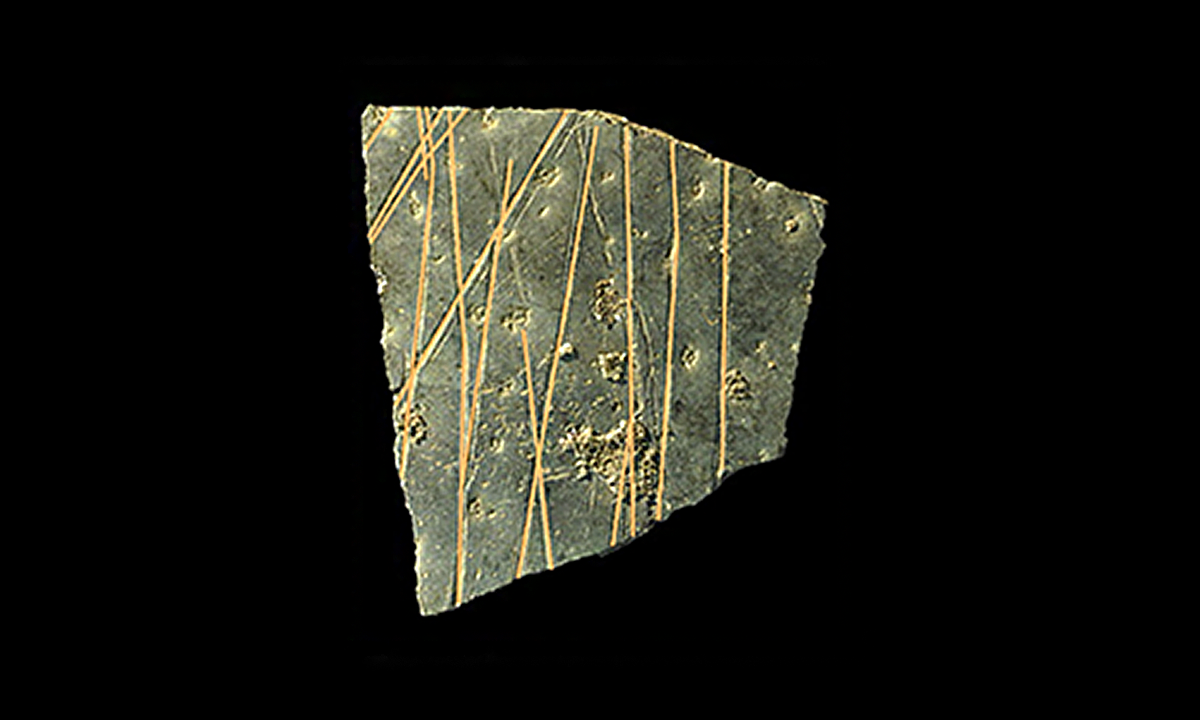

The researchers identified tattoos on remains from 27 individuals, the majority of whom were under 11 years old and from the Kulubnarti site. More than one in five people from this site had tattoos, which were primarily located on the forehead, cheeks, or temples, and incorporated patterns of dots and dashes that often formed diamonds or squares. They may have been formed with a single puncture from a knife, instead of needles, as was a common practice in the region during the pre-Christian period. During that time, dotted diamond patterns across people’s bodies and crisscrossed patterns on people’s hands appeared to be common in Nubian tattoo art.

The Kulubnarti remains revealed that, as Christianity arrived in the region, tattooing “focused on highly visible locations on the face and used tools, patterns, and techniques that could be employed quickly,” the authors noted. Because young Nubian children were the most common recipients of tattoos, it may have been tricky to keep them still and apply particularly intricate designs. These shifts could have transpired as early as the seventh century A.D. The Kulubnarti markings examined in the new paper may be the oldest recorded examples of the Christian tattoo traditions now practiced in Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt—there, cross tattoos on the forehead often “mark Christians permanently as believers,” the authors wrote.

Read more: “This Mummy’s Tattoos Are Better Than Yours”

It’s also possible that the tattoos were used in medicinal contexts. Due to their positioning on the head and their prevalence among young children, among other factors, the authors suggested that they were used to treat headaches or high fevers—common symptoms of malaria, a condition that has been documented in that region for centuries and is currently most severe in children under 5 years old. Ethnographic research from the 20th century has also highlighted various medicinal applications of tattoos in North Africa.

The authors hope more researchers take a close look at ancient tattoos, which can be easy to miss without the right techniques—this team was the first to identify these markings on remains of people from Kulubnarti. Even more millennia-old markings may be hiding in dig sites and anthropological research collections, waiting to be discovered. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: From Austin, A., et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025).