On this day 40 years ago, the nation watched with excitement as NASA prepared to launch the first civilian into space: Christa McAuliffe, a teacher from New Hampshire, trained for months to join six astronauts aboard NASA’s Space Shuttle Challenger. She planned to film a series of science lessons aboard the spacecraft, including two that would be aired on PBS.

But just over a minute after the Challenger took off from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, millions of viewers around the country—including children in schools—watched the spacecraft explode on their television screens. And hundreds of people gathered near the launch site saw the tragedy unfold right before them, including the crew’s families. The accident killed the entire Challenger team onboard.

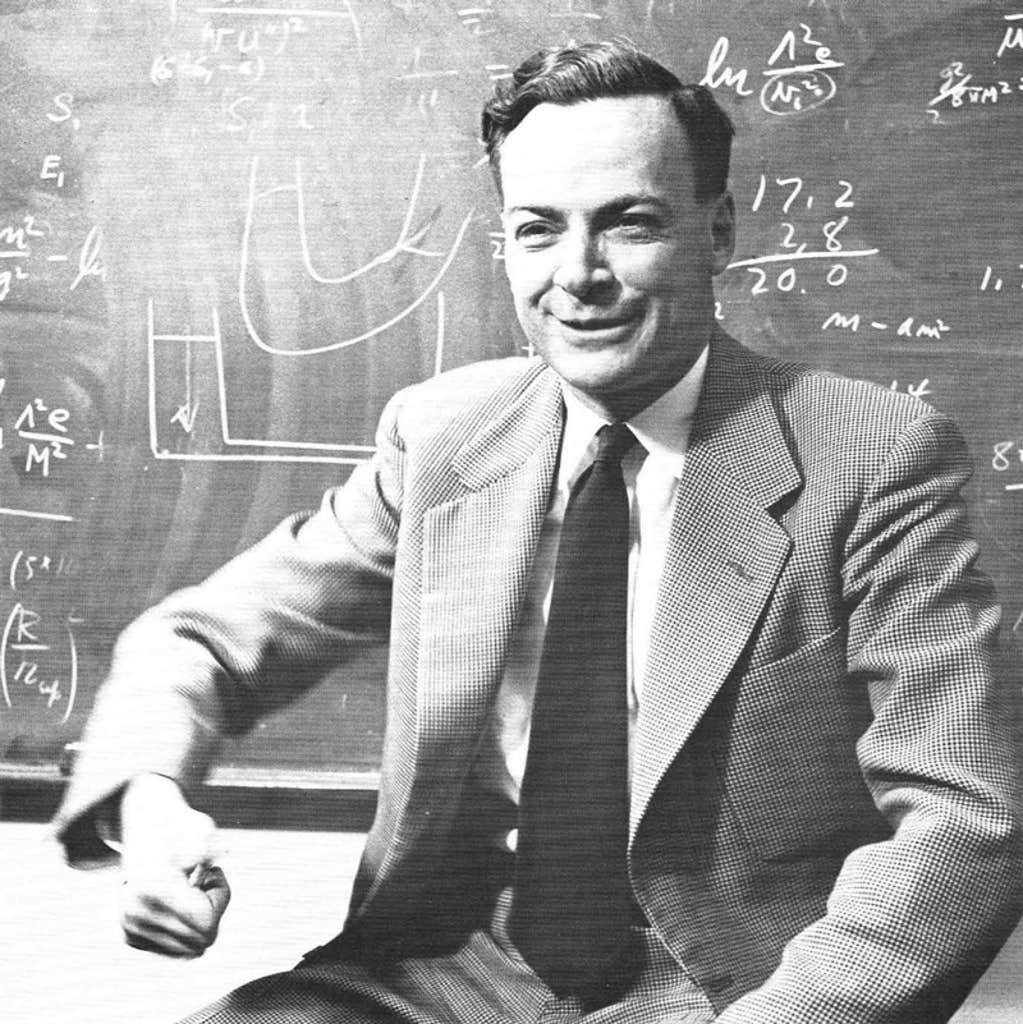

Days after the tragedy, President Ronald Reagan established a commission to investigate the accident. This group of prominent experts included retired astronaut Neil Armstrong, then-active astronaut Sally Ride, and physicist Richard Feynman. He had reached scientific stardom in the mid 20th century for his role in the Manhattan Project and his work visualizing the complexities of quantum mechanics, and in 1965, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Feynman was invited to the commission by NASA’s Acting Director William Graham, his former student at the California Institute of Technology. “When I heard it would be in Washington, my immediate reaction was not to do it,” he later wrote for Physics Today. “I have a principle of not going anywhere near Washington or having anything to do with government.”

Despite his initial reluctance to join the commission, it was Feynman who ultimately cracked the mystery behind the Challenger disaster.

Not long after joining the commission, the famed physicist met with members of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to learn more about the space shuttle. He quickly formed a theory on the system’s fatal flaw: Rubber rings known as O-rings that sealed the joints of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters had been scorched by hot gas multiple times, causing erosion.

Feynman later concluded that some of these rings failed to expand, allowing sizzling gas to escape one of the solid rocket boosters and burn a hole in an external fuel tank that contained hydrogen—prompting the massive explosion. In fact, these rings were never intended to be used to cover expanding gaps, he found.

During the official investigation, Feynman said he felt frustrated by the slow pace and “time-consuming” public meetings and briefings “of so little use.” He did his own research and met privately with NASA officials, and even created his own report that he released publicly.

In his report, he noted that NASA management had estimated a 1 in 100,000 chance of catastrophe with the space shuttle, while engineers put it at around 1 in 100. Based on the fact that the shuttle had launched plenty of times without incident, he explained that “obvious weaknesses are accepted again and again, sometimes without a sufficiently serious attempt to remedy them, or to delay a flight because of their continued presence.”

And NASA had assembled the space shuttle’s main engine all at once without testing individual parts separately, he pointed out. This makes it harder to determine individual issues.

Read more: “What Impossible Meant to Richard Feynman”

Feynman also criticized the model used to gauge the safety of the O-rings, and noted that NASA was aware they had been eroding.

Most famously, he found that the rubber can’t expand in temperatures at or below 32 degrees Fahrenheit—on the unusually chilly day of the Challenger launch, morning temperatures dipped to the 20s. Engineers from the company who made the solid rocket boosters had warned NASA the day before the launch about the compounding risks of frigid temperatures and O-ring erosion.

To demonstrate this tragic oversight, Feynman dropped a sample of the O-ring rubber in a glass of ice water. The rubber grew rigid in the glass, proving Feynman’s point. “I believe that has some significance for our problem,” he said at a February 1986 hearing of the Challenger commission.

For more than two years after the Challenger explosion, NASA put a pause on sending astronauts into space as they redesigned the space shuttle. The agency successfully blasted off space shuttle missions over the following decades, and the spacecraft was used to deliver components of the International Space Station. But in February 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia broke apart when reentering Earth’s atmosphere. Space shuttle missions began again in 2005, but NASA concluded the program in 2011.

Astronauts continue to honor the crews of the Challenger and Columbia missions. In 2017 and 2018, educators-turned-astronauts Ricky Arnold and Joe Acaba performed lessons designed by McAuliffe during their time on the International Space Station—ensuring that her work still reached children around the country. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: NASA