The deep seabed offers an alluring source of minerals to sustain our modern lifestyles. But the same sediments that yield valuable substances, from rare earth elements to copper and manganese, may also harbor unexplored ecosystems teeming with organisms new to science.

Potato-sized rocks dubbed “polymetallic nodules” have formed over millions of years from the precipitation of elements from seawater. These nodules started attracting commercial interest as early as the 1960s for their deposits of nickel, cobalt, copper, manganese, and trace amounts of rare earth elements like lithium and titanium used in battery technology.

Now, new findings describe an ecological cost of mining the nodules—such activities may impact undiscovered species before they are found and described.

In 2022, in a test of the feasibility of deep-sea mining, more than 3,300 tons of polymetallic nodules were collected almost 2.5 miles down on the abyssal plain of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Mining companies targeted an area called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Mexico, that’s known to have dense concentrations of nodules. A robotic nodule collection vehicle traversed nearly 50 miles of seafloor and used what’s called a riser-pipe to bring nodules, sediment, and anything else embedded in the substrate to the surface.

To ascertain the impacts of the mining, researchers worked in conjunction with the feasibility test to conduct a pre-post study of deep-sea fauna in the area that was mined. From 80 sediment samples, a team of scientists measured the abundance and diversity of sediment-dwelling organisms for two years before and two months after the test mining.

“The research required 160 days at sea and five years of work,” said University of Gothenburg marine biologist and co-author Thomas Dahlgren in a statement. “Our study will be important for the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which regulates mineral mining in international waters.”

Read more: “The Challenge of Deep-Sea Taxonomy”

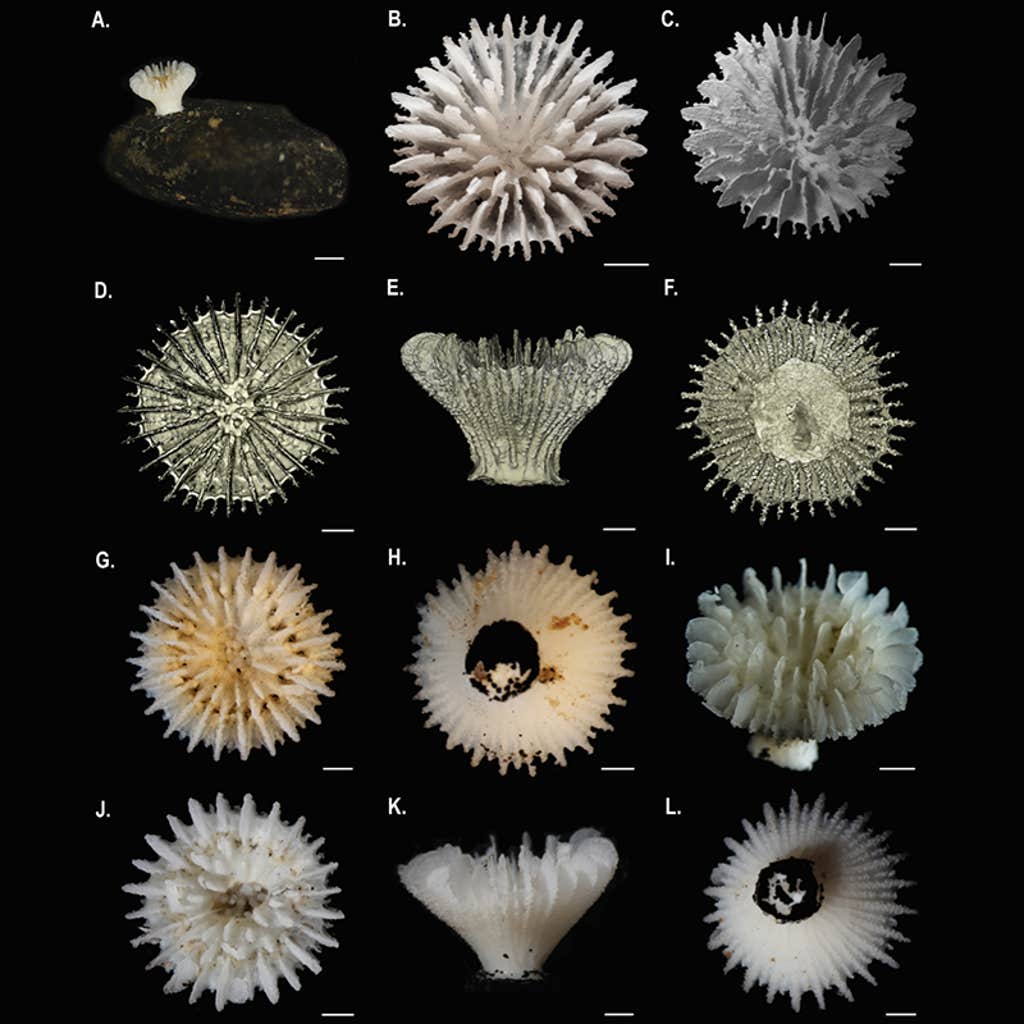

The results showed that, while this mining method has less of a negative ecological impact than expected, most of the disturbed species had not even been described by scientists yet. The 788 species identified through molecular DNA analysis included new species of marine bristle worms, crustaceans, and mollusks including both snails and mussels.

Post mining, the number of animals in the nodule extraction machine’s tracks decreased by 37 percent, with a 32 percent reduction in species diversity. So, while the deep-sea fauna was not totally wiped out by the nodule mining, certain species were eliminated.

“It is now important to try to predict the risk of biodiversity loss as a result of mining,” said Adrian Glover, co-author from the Natural History Museum of London. “At present, we have virtually no idea what lives there.”

There are likely to be many more undiscovered species lying in wait in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone and other areas attractive to deep-sea mining interests. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Craig Smith / ABYSSLINE