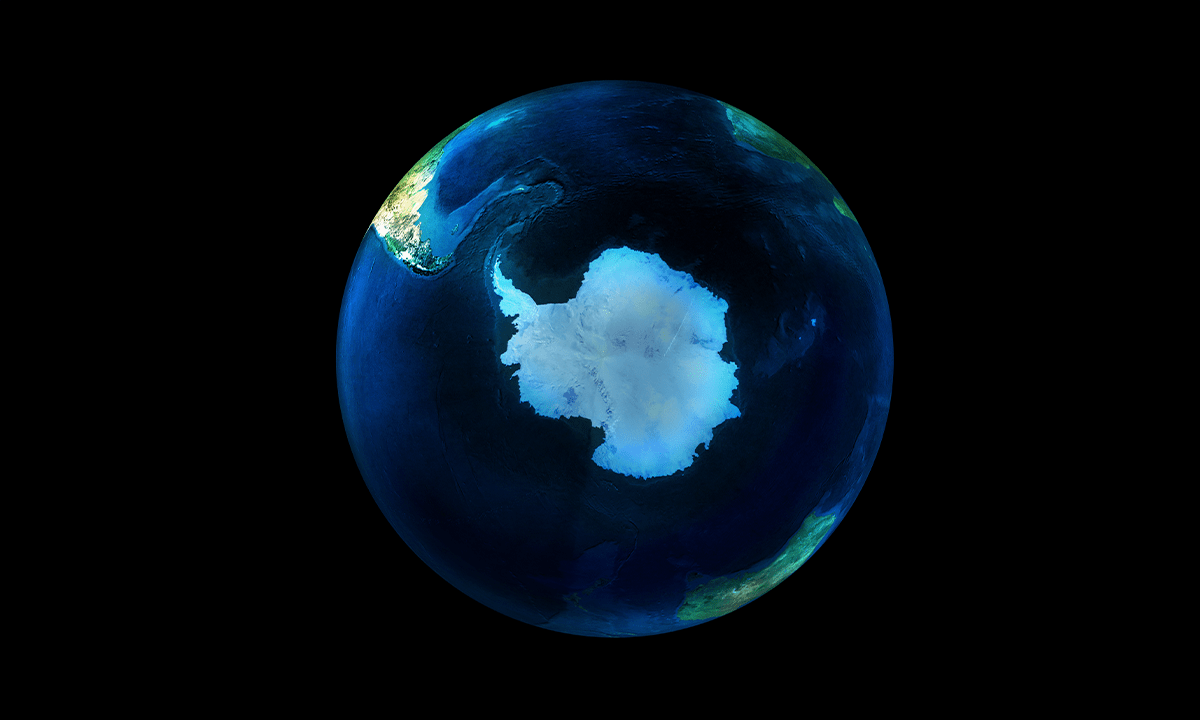

From space, planet Earth looks like a perfect sphere. But it’s not. Obviously, the crust of the Earth is irregular, covered in jagged mountains and deep oceanic trenches, but even if it were completely smooth and covered in water, the surface of this hypothetical ocean planet would still show some variations.

That’s because of differences beneath the crust of the Earth. Different densities of subsurface rocks cause the strength of gravity to fluctuate, and while these fluctuations are small, they can have big effects, especially on oceans.

One area with the weakest gravity is beneath Antarctica, where the surface of the ocean sits slightly lower relative to the center of the Earth. So how did this mysterious gravity hole get there? To find out, Alessandro Forte of the University of Florida and Petar Glišović from the Paris Institute of Earth Physics relied on data from earthquakes.

Read more: “So Much Depends Upon Antarctica”

“Imagine doing a CT scan of the whole Earth, but we don’t have X-rays like we do in a medical office. We have earthquakes. Earthquake waves provide the ‘light’ that illuminates the interior of the planet,” Forte explained in a statement.

Combining this data with physics-based modeling allowed them to construct a 3-D map. Then, using computer modeling, they retraced the flows of rock back in time to 70 million years ago. They published their findings in Scientific Reports.

Forte and Glišović discovered that, while the gravity hole started out fairly weak, it started getting stronger about 30-50 million years ago. During this time period, the South Pole experienced major climatic changes, including increased glaciation. Essentially, as the gravity hole picked up steam, Antarctica picked up ice.

Going forward, the pair hopes to investigate the link between gravity and glaciers using new models that include sea level and continental elevation changes, all to address the question: “How does our climate connect to what’s going on inside our planet?” Forte said. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: ConceptCafe / Shutterstock