The story of Andy Weir is a strange mix of fact and fiction. There’s the fairy tale success of his book, The Martian, which he self-published on his blog for free, intended for the few thousand fans he’d accumulated over years of hobby writing. Some of those fans wanted an electronic book version, which he made, and then a Kindle version, which he made too, charging the minimum price allowable by Amazon: $0.99. “That’s when I learned how deep Amazon’s reach is,” Weir would later tell an audience. Within four months, The Martian had risen to the top spot on Amazon’s sci-fi best-seller list, and two months later he had signed both a book deal with Random House’s Crown Publishing imprint and a movie deal with 20th Century Fox. The book is currently number 10 on The New York Times’ fiction best-seller list. The motion picture, which stars Matt Damon and is directed by Ridley Scott, is due to come out this year.

Then there’s the story inside the book itself: An astronaut gets left behind on Mars in a near-future NASA mission, and has to survive until help comes. This he does through physics and chemistry, algebra and pipe fitting, botany and celestial navigation, all described in meticulous detail, some of it even simulated with software that Weir wrote himself. The lesson to writers is clear: Details give you authenticity, and authenticity gives you the reader. Having a great protagonist helps too: Mark Watney is casual, funny, thoughtful, and self-effacing—much like Weir, as I discovered in conversation.

You’ve said that science can create plot. How did it do that in The Martian?

The basic roots are somebody who’s stranded away from civilization, to go back to Robinson Crusoe. So it’s not an innovative idea! But it’s just a really fun one to play with. I had my astronaut who’s stranded on Mars. All you have to do is start examining any aspect of his survival and you’ll quickly find the problems he runs into. He’s going to need food, but you can’t just create food that easily; you need to actually grow it. Doing some math on how long his supplies would last told me, well, it’s just implausible for his supplies to last long enough. So that’s a simple case where science creates plot. Then he needs to have this much water to grow food. He can get plenty of dirt from outside, but he needs the dirt to have a certain amount of water. I did all the math to figure out how much water he’d need, and it was just implausible that a manned mission would carry that much water. It was like hundreds of liters. And so I said, well, that’s interesting. I didn’t know that and I hadn’t thought of that until I sat down and did the math. Then I had this whole plot where he has to go create water. Doing the math on every little aspect of his life revealed the many places where he was in mortal danger.

Your book seems to appeal unapologetically to a nerd audience by just saying, look, I’m going to explain to you the fine details of how everything works.

Yes, I think that’s definitely accurate. When I wrote it, it was a serial that I was posting to my website one chapter at a time. I had about 3,000 regular readers that I’d accumulated over 10 years of writing fiction and web comics and stuff like that. I was really writing it for them. I didn’t have market appeal in mind when I was writing the book. I was thinking, I have 3,000 hardcore nerds that are my readers, because I’m a hardcore nerd, and I’m going to write a story that they’ll enjoy. So that’s why it was pretty heavy on the math and the science and the show-your-work kind of stuff, because that’s exactly what my readers like. I had no idea that it would end up being popular in the mainstream, and still to this day I don’t know what I did right. I don’t know how this story that was basically a prolonged math problem ended up getting so popular among people who aren’t that interested in math!

For some reason I was excited to learn you can make water from hydrazine rocket fuel.

Well, that particular one was just a case of looking up how hydrazine works. I was like, he’ll have some rocket fuel left over, what’s it made of? I could choose any of the many rocket fuels available, and I’m like, well, let’s say they did hydrazine, how do hydrazine engines work? And it was just looking that up, just lots and lots of Google searches, you know, that sort of thing. It’s awesome to have an interest in science in the modern era where you can just look literally anything up!

Can you think of another book that does such a deep dive on math and physics?

Larry Niven’s Ringworld does do actually quite a lot of math. In Ringworld the book actually explains, here’s the mass that you would need to make a ringworld, and if it’s spinning at this rate the atmosphere would be kept in and the gravity would be created through centripetal force. If you check his numbers, it’s actually accurate.

Although you worked very hard to make the facts in the book accurate, you left in some inaccuracies on purpose. Why?

It’s the beginning setup, where there’s the dust storm that makes [the astronauts] do an emergency evacuation and stabs Mark with an antenna. None of that would happen. Realistically, that wind would not have enough force to do anything. So nothing would get ripped off its foundations, no one would be in danger, no one would get knocked over. That was a deliberate concession I made, because I just thought it was more dramatic to have him get stranded by a weather event. It kind of plays well into the theme of it’s him versus Mars, and it starts off with Mars smacking him around. But realistically, that could not possibly happen.

I have 3,000 hardcore nerds that are my readers, and I’m going to write a story that they’ll enjoy.

After a while I took the book’s facts as gospel. I could’ve told someone at a cocktail party the wrong thing about Martian storms!

Yes, I would’ve been the indirect cause of that social embarrassment for you! You know, I spend a lot of time trying to figure out why people like the book, because I’d like to write another book that they like that much. One of the things I get from readers is that they all felt the same as you. They felt very, very quickly they had complete confidence in the kind of legitimacy of the science. You don’t need to actually be right, you just need to sound right. You just need the reader to have faith in you, because when you’re reading a book you can’t help it, or I sure as hell can’t help it. When I’m reading a book there’s a meta process going on in my brain, just critically analyzing things. It’s like, oh, I don’t know if that’s realistic! It’s this annoying little voice in the back of my head trying to ruin my fun. If you can make that voice in the reader’s head not have much to say, then they enjoy the book more.

Did it ever bother you when you finished the book that every single thing was accurate except the storm?

Yes. It bothered me. It was a tactical decision. I flip-flopped back and forth many times. I was like, I can rewrite this, I can rewrite this to make it realistic. But I just couldn’t come up with anything that was nearly as exciting or dramatic.

If you had a choice of career, would you rather be a scientist at NASA or would you rather be a sci-fi writer?

Ha! That’s a tough call. I’m going to have to say sci-fi writer, and the reason is because I love watching what NASA does, but being a part of it is really grueling. Also I’ve worked for the government before. It can be large and bureaucratic and it can be pretty unpleasant. It’s like, I like watching football, but I don’t have the stuff to be a football player. Ignoring my lack of talent or physical presence, it’s just the effort required to be a professional athlete, the sacrifice, the pain, you know, all that stuff, the work required. I’d rather just watch other people do it!

What’s the biggest challenge in putting humans on Mars?

It’s getting off of the surface of Mars when you’re done, which is why some people came up with the idea of one-way trips to Mars and colonization, because it’s really that hard. Think about the kind of rocket we need to get off of Earth; it’s usually really big. Then compare that to the ascent stage of the lunar module, which is all you needed to get off the moon; it was this little box. That’s the difference that gravity and atmosphere makes. When people talk about methane oxygen fuel, they’re talking about making fuel out of the Martian atmosphere, which is covered in my book too. That’s how the MAV ascends; it’s pre-landed and then it just sits around making fuel. If you can make yourself, I don’t know, 15,000 kilograms of rocket fuel out of the Martian atmosphere, then that’s 15,000 kilograms you don’t need to bring with you.

Have recent discoveries changed your thinking about a Mars mission?

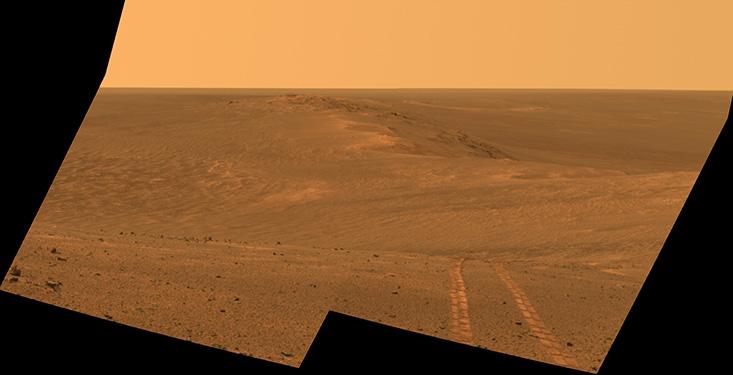

At the time that I wrote my book, Curiosity hadn’t landed yet and they hadn’t discovered how much water there was. It was since the book was released that we discovered there’s actually tons and tons of water on Mars. It’s all as ice crystals suffused in the sand, but if you take a cubic meter of dirt from Mars, or at least from the area Curiosity is in, you get something like 35 liters of water. It’s this huge amount, far more water than anybody expected, which is really exciting because the only missing thing to making your own rocket fuel on Mars was hydrogen. The original plan was to bring the hydrogen with you, and for every kilogram of hydrogen you bring you can make 13 kilograms of rocket fuel. But now you don’t even need to do that. Now you just need rovers and machinery to harvest water out of the soil, and you can literally send a device to Mars that can make its rocket fuel with nothing. Which is really exciting!

The environment in your book was literally being discovered while you were writing.

It’s funny: In the book Mark travels through a valley called Mawrth Vallis when he’s driving his rover. He uses it as a navigation aid, and it is the easiest way to get from this point to that point. After I’d written the book and it was already out in eBook form, they were starting to pick landing sites for Curiosity. They had it down to their four final options. One of them was Mawrth Vallis, and it was like, oh crap! If they land that thing in Mawrth Vallis, then anybody with a scientific bent, anybody who knows anything about Mars when reading this, it’d be like why did Mark just drive right by the Curiosity?

If you wrote the book today, would Mark harvest his water from soil?

Actually no, because I really liked all the stuff Mark had to do to make water; I think that was really good in the story. So I would just say, oh Acidalia Planitia is where Mark is, which is actually a desert. It turns out there’s very, very little water suffused into the dirt there. I liked the way that worked out, the part where he’s reducing hydrazine to make water.

There’s just this inherent need to cooperate in human nature. And I think it’s really beautiful.

What do you think about the recent observation of methane bursts in the Martian atmosphere?

It’s really exciting. It makes you dare to dream, because there are two things that create methane on a planet. One of them is geological activity and the other one is life. The thing is, methane breaks down very quickly in the atmosphere, especially on a planet like Mars that has no magnetosphere to deflect ionizing radiation. Solar radiation comes in in various forms and smacks the methane and the methane breaks down into smaller molecules. So methane doesn’t last very long. The question is, Mars is geologically dead, it has no plate tectonics, it does not move anymore. So if you have a bunch of methane in the atmosphere, how did it get there? People don’t want to say that proves that there’s life because they don’t understand what’s going on yet, but it’s pretty exciting because methane is an organic molecule!

What could it be?

Well, there’s any number of things it could be. I’m maybe a bit of a pessimist, but the most likely option is that Mars isn’t as geologically dead as they suspected and there might be, you know, pockets of methane gas that just kind of out-gas here and there and have been for millions of years. If it were life, then it would have to be microbial life and there’d be pockets of microbial life left over from a possibly much more life-riddled past. If Mars ever had life, its most interesting period would’ve been about a billion years ago when it still had liquid water.

You say you’re a pessimist, but your book is a pretty optimistic one.

On the grand scheme of things with dystopia at zero and utopia at 10, I’d say I predict about a six or a seven. The thing to remember is The Martian doesn’t take place in some far-off, distant, unimaginable future. It takes place maybe 20 years from now. It’s not like, oh, I just took my flying car to work today. Yes, there’s cooperation with the Chinese, but I think we should be cooperating with them more on space stuff, and I think it’s inevitable. Bear in mind, at the height of the Cold War we cooperated with the Russians on space stuff. It’s just a thing we do! I have more faith in humanity maybe than others do, and there is a general optimistic kind of feel to the book, like we can do this, and people tend to inherently want to work together when there’s a problem.

Where does that faith come from?

I don’t know! Maybe observation of thousands of years of history. It’s like we hyperfocus on the times when people are assholes. And we pay attention to the murderers and the rapists, and that’s the news that we see. But we also take it for granted just without even thinking about it that when there’s an earthquake and there’s a bunch of people trapped in rubble, then there are thousands of people trying to help them. When there’s a tsunami or a disaster every country on earth offers their help. When somebody gets lost hiking in the woods, 500 people go out looking for them. There’s just this inherent need to cooperate in human nature. And I think it’s really beautiful.

What’s your new book about?

It’s tentatively titled Zhek, and it’s much more soft science fiction. It’s basically about aliens that attack Earth, and there’s faster-than-light travel and telepathy and the good old-fashioned stuff.

Did you think about making another super-accurate book like The Martian?

Yes, yes. I actually spent months working up a pitch for another book that was going to be technically very accurate. It was going to be about a moon base. And everything about the moon base was physically accurate, like you could actually make a moon base with today’s technology following these plans, type of thing. The publisher said, well, the setting that you’ve made for this is really cool, but the story that you came up with to take place in the setting is just not that interesting. So they rejected it! So getting your book on The New York Times’ best-seller list doesn’t mean you get a rubber stamp on your next book!