One morning in Maine, soon after dawn, I stood by the ocean just as a light fog began moving in. The rising sun became a gauzy fire. Suddenly, the air started to glow. Fog scattered the sunlight, bounced it around and back and forth until each cupful of air shone with its own source of light. In all directions, the air beamed and shimmered and glowed, and the gulls stopped their squawking and the ospreys became quiet. For some time, I stood there spellbound by the silence and the glowing air. I felt as if inside a cathedral of sunlight and air. Then the fog burned away and the glow disappeared.

Hinduism has a concept called darshan, which is the opportunity to experience the sacred. One is advised to be open to such experiences.

I’m a scientist and have always had a scientific view of the world—by which I mean that the universe is made of material stuff, and only material stuff, and that stuff is governed by a small number of fundamental laws. Every phenomenon has a cause, which originates in the physical universe. I’m a materialist. Not in the sense of seeking happiness in cars and nice clothes, but in the literal sense of the word: the belief that everything is made out of atoms and molecules, and nothing more. Yet, I have transcendent experiences. I witnessed the air shining that morning in Maine. I’ve communed with wild ospreys. I have feelings of being part of things larger than myself. I have a sense of connection to other people and to the world of living things, even to the stars. I have a sense of beauty. I have experiences of awe. And I’ve had transporting creative moments. Of course, all of us have had similar feelings and moments. While these experiences are not exactly the same, they have sufficient similarity that I’ll gather them together under the heading of “spirituality.” I will call myself a spiritual materialist.

Everything is made out of atoms and molecules, and nothing more.

I would argue that spirituality follows naturally from a material brain—through the path of consciousness, high intelligence, and the evolutionary forces that shaped Homo sapiens. In understanding the origins of spirituality in this way, I do not mean to diminish such a majestic and profound feeling. Spiritual experiences are among the most memorable moments of our lives. I would like to suggest that they are as natural as hunger or love or desire, given a brain of sufficient complexity.

This “spiritual materialism” provides a framework for understanding spirituality without reference to an all-powerful, intentional, and supernatural Being (God). Such an exploration relates to intellectual movements like secular humanism—the idea that humans can live a moral and self-fulfilled life without belief in God—while at the same time recognizing the importance and validity of spiritual experiences.

Those who believe in an omniscient and purposeful Being that created the universe often associate spirituality with that Being. One of the most beautiful and compelling statements of that association can be found in William James's landmark book The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which a Christian clergyman describes an immediate and vital transcendent experience:

I remember the night, and almost the very spot on the hilltop, where my soul opened out, as it were, into the Infinite, and there was a rushing together of two worlds, the inner and the outer. It was deep calling unto deep—the deep that my own struggle had opened up within being answered by the unfathomable deep without, reaching beyond the stars. I stood alone with Him who had made me, and all the beauty of the world, and love, and sorrow, and even temptation. I did not seek Him, but felt the perfect unison of my spirit with His. The clergyman clearly attributes to God his profound feelings of connection to the cosmos.

Of course, one of the best-known spiritual experiences and its association with God is the Old Testament account of Moses and the burning bush:

And the angel of the LORD appeared unto him [Moses] in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.

These experiences, which express many of the features of spirituality as I have defined it—feelings of connection to nature, the cosmos, and other people; the feeling of being part of something larger than one's self, the appreciation of beauty; the experience of awe—are religious experiences, in that they are all mediated by an omniscient and purposeful Being and Creator we call God. As such, the experiences may be considered to derive from God, or from the God-like soul in us, or from the pervasiveness of God in nature and the cosmos. For the unnamed clergyman and Moses, the existence and spiritual power of God are implicitly assumed.

I respect these beliefs and their divine attributions. My aim is to show that the same spiritual feelings can arise completely from the forces of Darwinian natural selection and the capacities of a highly intelligent brain, without other agency. In other words, I am discussing a nonreligious spirituality and its evolutionary origins, although the feelings of connection and awe may be quite similar to those of religious spirituality.

When I talk about the forces of natural selection, I do not necessarily mean that every element of spirituality, as I have defined it, has direct survival benefit. In 1979, evolutionary biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin coined the word "spandrel" to mean animal traits that were not adaptive in themselves but rather by-products of other traits that did have survival benefit. For example, eye color and earlobe size are not traits with any particular survival value, but bodily color and ears clearly have survival benefits. The ability to write poetry does not have any evident evolutionary advantage, but such ability may be the by-product of a sensitivity to sounds and rhythms, which probably did have survival benefits.

Spirituality is a spandrel. The desire for connection and belonging, to nature and to other people; the feeling of being part of something larger than ourselves; the appreciation of beauty; the experience of awe—all are byproducts of other traits that had evolutionary benefit. Another aspect of spirituality is “the creative transcendent,” a name I give to that exhilarating, soaring sensation when we produce something new in the world, discover something new, find ourselves in a state of pure seeing. Painters, musicians, dancers, novelists, scientists, and all of us have experienced the creative transcendent.

The creative transcendent could well be a by-product of the urge for exploration and discovery—finding new hunting grounds, new sources of water, new sources of food. A painting, a musical composition, a poem, a novel idea, a sudden insight about how to decorate a room—aren't they all explorations of a kind? And what exactly are we exploring? I suggest that in the creative transcendent experience, we are exploring both the outer world beyond ourselves and the inner world of our minds. We are exploring our hidden capacities. When we create, we discover new things about ourselves. We find secret doors. And, perhaps most importantly, we uncover new connections between ourselves and the rest of the cosmos.

Creativity in science is somewhere between discovery and invention.

The creative transcendent involves a total loss of self and embodiment. According to the "emptiness" ideas of Vajrayana (Tibetan) Buddhism, the self is an illusion. And the ego is an obstacle. Indeed, in Buddhism, all suffering is attributed to excessive attachment of our ego to things we do. And that ego, or sense of self, disappears during the creative transcendent experience.

During the creative moment, we have no sense of our self, our body, even time and space. We are simply in the zone. We have entered a state of pure seeing. Associated with that experience is a letting go. At least temporarily, we forget our cares, we leave behind the constant rush and heave of the world. Bodiless, we travel to some other space. I am tempted to call it an ethereal space, but, being a materialist, I believe that this other space is rooted in the material brain. That said, the material brain is capable of wondrous things. And the trip seems effortless. We do not struggle in the creative transcendent. We glide.

In 1926, the British social psychologist and educator Graham Wallas proposed that creative thinking follows a series of stages: preparation, incubation, illumination, and finally verification. In the preparation stage, the person does her homework or research in a field or art form or any other endeavor, masters the tools of the craft, and defines some problem. In the incubation stage, the person mulls over the problem in various ways, sometimes unconsciously. In the illumination stage, the person achieves a new insight or shift of perspective. And in the verification stage, the person puts the insight to the test and works out the consequences. The creative transcendent would occur during the incubation and illumination stages. Here are some personal accounts.

The first is by the distinguished 19th-century mathematician Henri Poincare. Mathematical creativity is an intriguing special case of the creative transcendent. Practitioners and philosophers disagree on whether mathematical truth exists out there in the world, independent of the human mind—in which case mathematicians discover what is already there, like coming upon a new ocean—or whether mathematical ideas, theorems, and functions are invented out of the mind of the mathematician.

In any case, Poincare wrote these words about one of his creative experiences: "Every day I seated myself at my work table, stayed an hour or two, tried a great number of combinations and reached no results. One evening, contrary to my custom, I drank black coffee and could not sleep. Ideas rose in crowds; I felt them collide until pairs interlocked, so to speak, making a stable combination. By the next morning I had established the existence of a class of Fuchsian functions."

I was afraid to disturb whatever strange magic was going on in my head.

Painting is a more familiar form of creative activity, requiring both disciplined training and spontaneous inspiration. My wife spent 10 years studying the craft, drawing plaster busts to master light and shadow and rounded edges; now, as a professional, she will sometimes spontaneously decide to add an accent of red in the corner of a still life to provide balance and interest.

The painter Paul Ingbretson, a contemporary leader of the Boston School of American art and past president of the Guild of Boston Artists, told me, "All my awareness [while painting] is fixed on the exercise of the search for the likeness and the beauty. I do get rewards every 20 minutes or so as I accomplish minor missions and see the whole coming into view. A bit of a high, yes. Like hitting a shot in sports ... I am always the conscious vehicle, always submitting to bringing the beauty of the thing itself. My job is to get out of the way. And in that way, I lose myself ... Whenever I come close to the magic, I know it is something bigger than me. Even truth is merely a vehicle for beauty. I remember the first time I saw the beauty of three colors as a unity, I thought this is too much for me—like the Holy Land, perhaps. I remembered Moses taking off his shoes at the burning bush. Like that."

Creativity in science is somewhere between discovery and invention. There is already a large body of established facts about the world that cannot be circumvented when inventing new theories, what the physicist Richard Feynman described as creating while wearing a straitjacket. Scientific creativity takes place at the boundary between the known (the accumulated facts from prior experiments) and the unknown (regions of the physical world that have not yet been explored). In his autobiography, the physicist Werner Heisenberg describes the transcendent moment when he realized that his new theory of quantum mechanics would succeed in describing the hidden world of the atom. At the end of May 1925, after months of struggling with his theory, he fell ill with hay fever and took a two-week leave of absence from the University of Gottingen.

I made straight for Heligoland, where I hoped to recover quickly in the bracing sea air ... Apart from daily walks and long swims, there was nothing in Heligoland to distract me from my problem ... When the first terms [in the mathematical equations] seemed to accord with the energy principle, I became rather excited, and I began to make countless arithmetical errors. As a result, it was almost three o'clock in the morning before the final result of my computations lay before me ... At first, I was deeply alarmed. I had the feeling that, through the surface of atomic phenomena, I was looking at a strangely beautiful interior, and felt almost giddy at the thought that I now had to probe this wealth of mathematical structures nature had so generously spread out before me. I was far too excited to sleep.

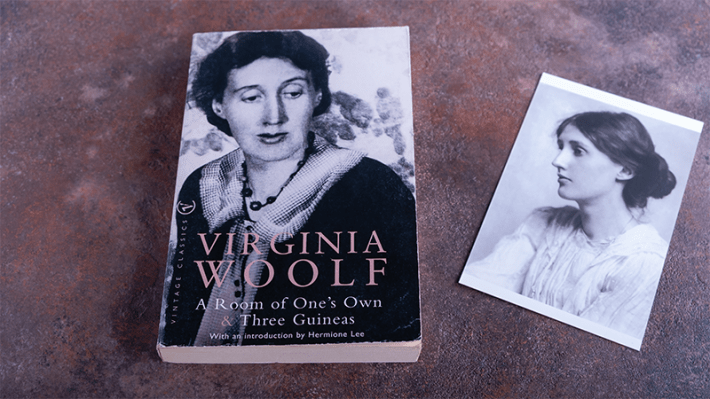

In the literary arts, writers cannot fully plot out their characters' actions, or else they will not come to life. There must be an element of surprise, even for the writer. The writer must disappear, or be a fly on the wall, listening to her characters speak rather than telling them what to say. In a speech delivered to the National Society for Women's Service in early 1931, novelist Virginia Woolf gave this description of her creative process:

A novelist's chief desire is to be as unconscious as possible ... I want you to imagine me writing a novel in a state of trance. I want you to figure to yourselves a girl sitting with a pen in her hand, which for minutes, and indeed for hours, she never dips into the inkpot. The image that comes to my mind when I think of this girl is the image of a fisherman lying sunk in dreams on the verge of a deep lake with a rod held out over the water … letting her imagination sweep unchecked round every rock and cranny of the world that lies submerged in the depths of our unconscious being.

Although the above accounts come from professional scientists and artists, we all have experienced the creative transcendent—from decorating a room to playing the piano to designing a marketing plan to giving birth to a child. Here’s one of my own experiences.

One of my first research problems as a graduate student in physics concerned the force of gravity—the question of whether the experimentally observed fact that all objects fall with the same acceleration is sufficiently powerful to rule out a group of theories of gravity, called nonmetric theories, in competition with Einstein's theory. In the grand scheme of physics, it was not so consequential a question, but it had not been previously answered. After an initial period of study and work, I had succeeded in writing down all the equations to be solved. Then I hit a wall. I knew I'd made a mistake, because a result at the halfway point was not coming out as it should, but I could not find my error.

Day after day, I checked each equation, pacing back and forth in my little windowless office, but I didn't know what I was doing wrong, what I had missed. Then one morning, I remember that it was a Sunday morning, I woke up about 5 a.m. and couldn't sleep. I felt extremely excited. Something was happening in my mind. I was thinking about my physics problem, and I was seeing deeply into it. And I had absolutely no sense of my body. It was an exhilarating experience, a kind of rapture—an experience completely without ego.

The closest physical analogy I've experienced to this creative moment is what sometimes happens when you are sailing a round-bottomed boat in strong wind. Normally, the hull of a boat stays down in the water and the friction of the water greatly limits the speed of the boat. But in a strong wind, every once in a while, the hull of a round-bottomed sailboat will lift out of the water, get on top of the water, and the frictional drag drops to almost zero. Then the boat leaps ahead. It feels like a gigantic hand has grabbed hold of your mast and yanked you forward. You go skimming across the water like a smooth stone. It's called planing.

I awoke on this morning, planing in my mind. Something had grabbed hold of me, but there was no "me." With these sensations surging through me, I tiptoed out of my bedroom, almost reverently, afraid to disturb whatever strange magic was going on in my head, and went to the kitchen table, where my crumpled pages of calculations lay before me. Within a few hours, I had found the error and solved my physics problem. I had discovered some small truth about the cosmos, a thing hidden until I found it. And yet the "I" was absent during the discovery. ![]()

Alan Lightman earned his Ph.D. in physics from the California Institute of Technology and is the author of seven novels, including the international best seller Einstein’s Dreams. His nonfiction includes The Accidental Universe, and most recently, The Transcendent Brain: Spirituality in the Age of Science. He is currently a professor of the practice of the humanities at MIT. He is the host of the public television series Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science.

Adapted from The Transcendent Brain: Spirituality in the Age of Science, by Alan Lightman. Copyright © 2023 by Alan Lightman. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Lead image: Shahril KHMD / Shutterstock