We pretty much know how all this ends—“this” being the time that life gets to enjoy existing on Earth. That Earth gets to enjoy existing at all. It goes something like this: It’s 5 billion years from now. The sun is growing unstable, running out of hydrogen fuel in its core. Eventually the core collapses under its own weight, heats up from all that mass squeezing together, and switches to burning another gas, helium. Its outer layers begin to puff up dramatically, vaporizing and then swallowing the two innermost planets, Mercury and Venus. Earth may be pushed to a wider orbit, or follow Venus and Mercury to fiery destruction.

This is not as big a deal as you might imagine, as life on Earth, at this point, had already ended billions of years ago. The slow brightening of the sun mounted a greenhouse effect, warming the Earth to temperatures too hot for life as we know it (a future we can look forward to about 1 billion years from now).

Appreciate what a special place our planet occupies.

Astronomers are now casting their gaze outward to write a compelling story of what happens from here. The scene could make an appealing setting for an epic sci-fi narrative: For a few hundred million years, the increase in heat from the main-sequence-star-turned-red giant transforms the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn into island paradises. The most massive ones—including Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa orbiting Jupiter; and Titan, orbiting Saturn—will melt into ocean-covered satellites with incredible views. This is the solar system’s true heyday, when it will boast more places to live within the “habitable zone” than at any other period. If humanity is still around, it will be a glorious time—for a time.

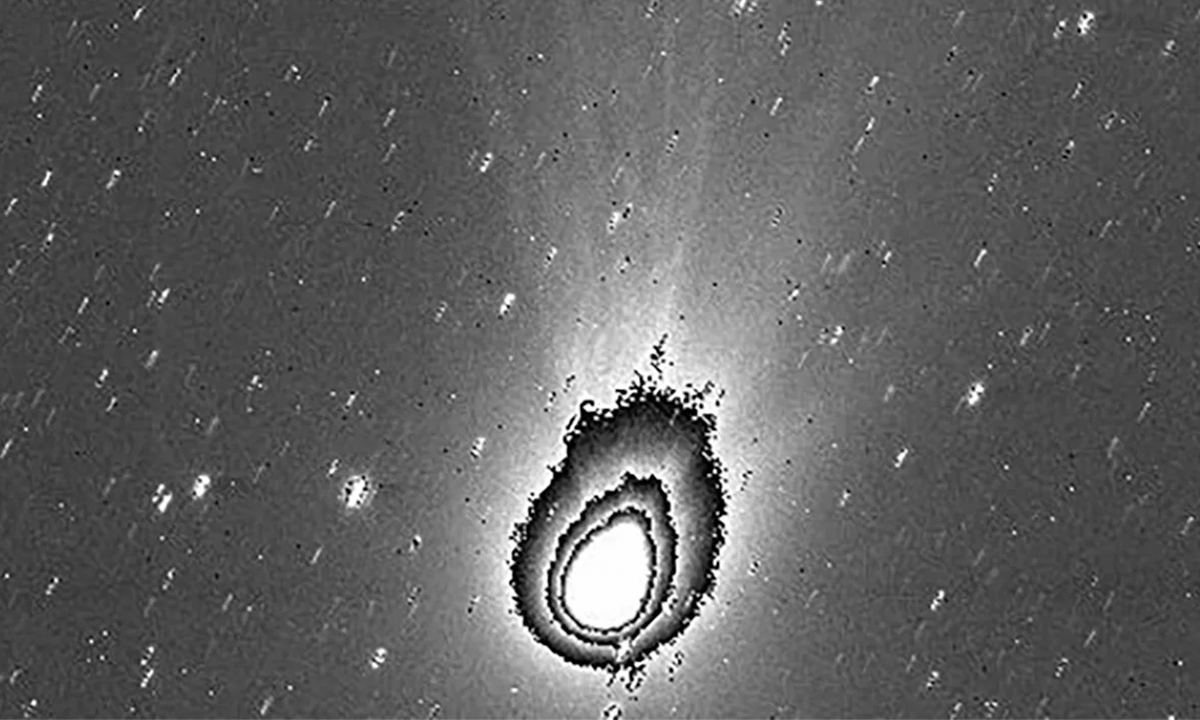

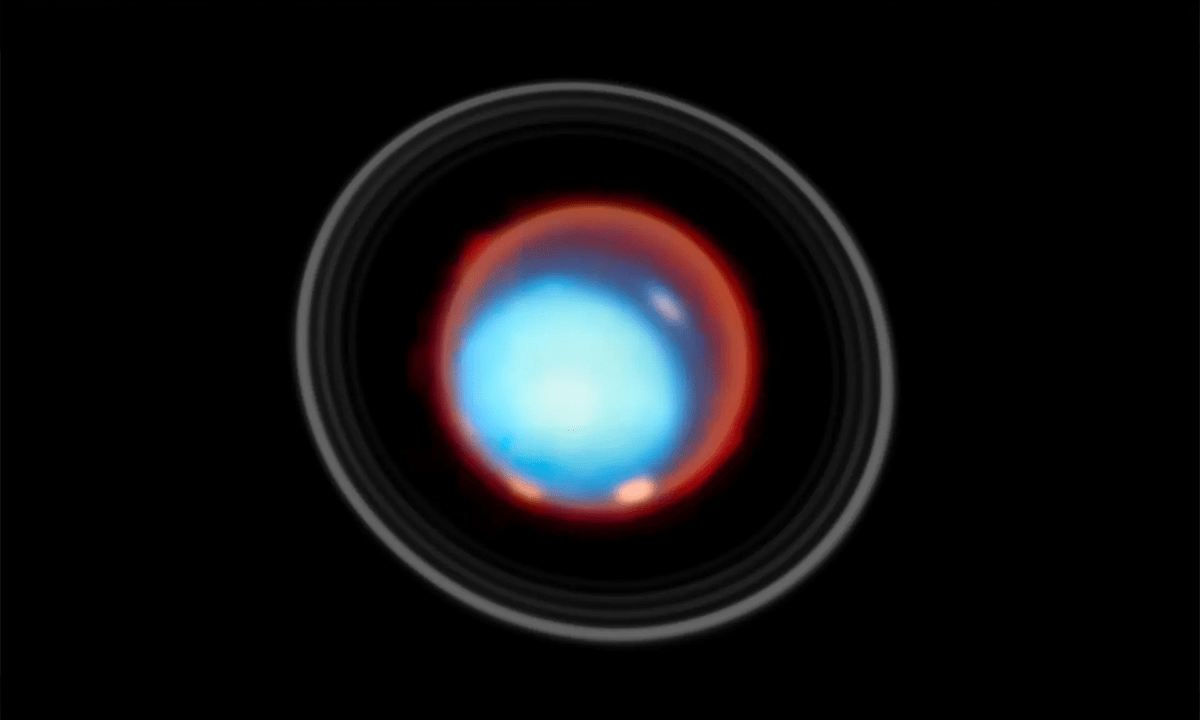

Nothing ultimately lasts, of course. The sun’s core runs out of helium fuel, and, unable to jump to a new source of fuel, collapses on itself again. The outer, puffy layers are shrugged off in a titanic wind, and lost to interstellar space. Anyone watching from afar would see a beautiful picture of a dense planetary nebula, more than 40 percent of the sun’s mass. The orbits of the planets respond to this loosening of gravity’s hold by stretching out, almost doubling in size. Our red giant-turned-white dwarf sun, with no source of internal heat, will soon start to cool down, only to get ever colder and darker. The ocean-covered paradise moons will quickly freeze over again.

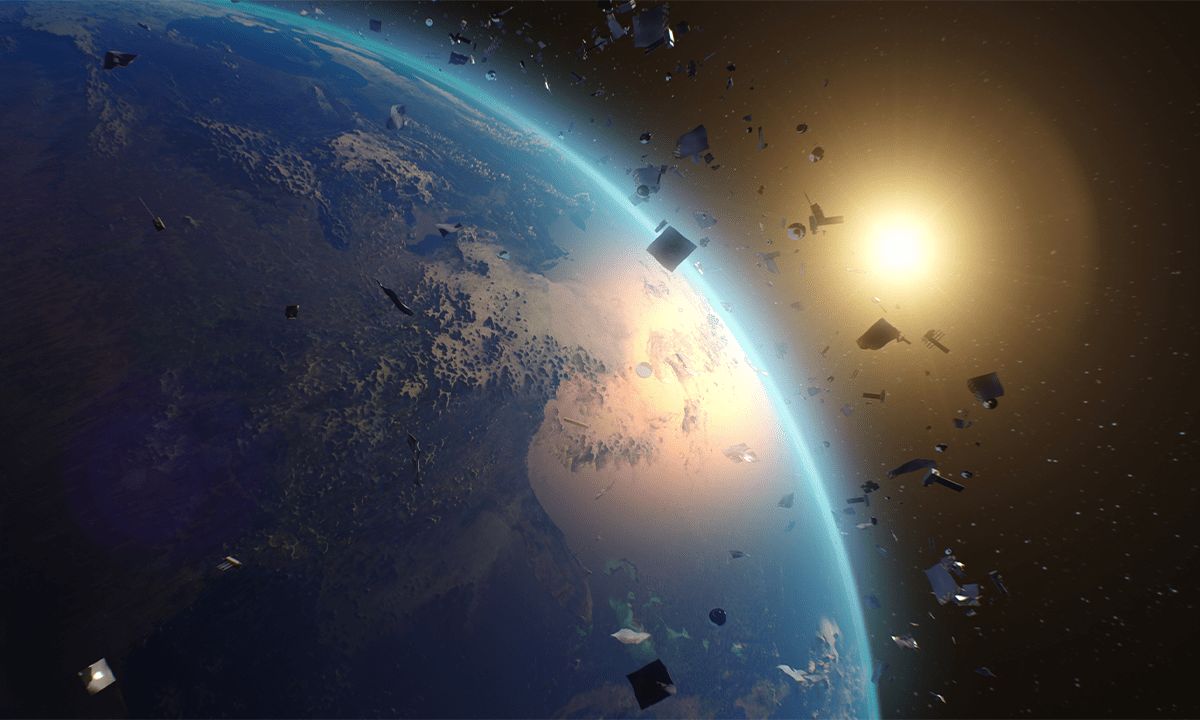

The orbits of asteroids and comets will be destabilized by the shift in the planets’ orbits. Many will end up on much larger paths, pass close to the white dwarf sun, and be torn apart by its gravity. Rocky and icy debris will slowly drip down onto the ever-cooling white dwarf sun, perhaps intermittently, long into the distant future.

This may seem like a dystopian fantasy, but it is strongly backed by observations and modeling. The 20th century saw astronomers figure out how stars evolve, and we now have a clear view of the future evolution of the sun into a red giant and then a white dwarf.

A surprising discovery of the past couple decades is that a significant fraction of white dwarfs are “polluted.” White dwarfs are either hydrogen- or helium-dominated, and in either case, any heavier elements settle out of their atmospheres in days to months, a cosmic blink of the eye. The fact that we observe heavy elements in white dwarfs’ atmospheres means that they were very recent pollution from objects that have fallen onto their surfaces. But which ones?

The abundance patterns of these heavier elements seen in some polluted white dwarfs are a close match to meteorites, providing circumstantial evidence that asteroids, and even rocky planets, may also have formed around—and ultimately been swallowed by—their central star. New dynamical studies have shown how giant planets gravitationally slingshot asteroids and comets when their orbits are shifted due to the evolution of the star into a white dwarf, depositing rocky (and sometimes even icy) material onto the white dwarf over billions of years.

If humanity is still around, it will be a glorious time.

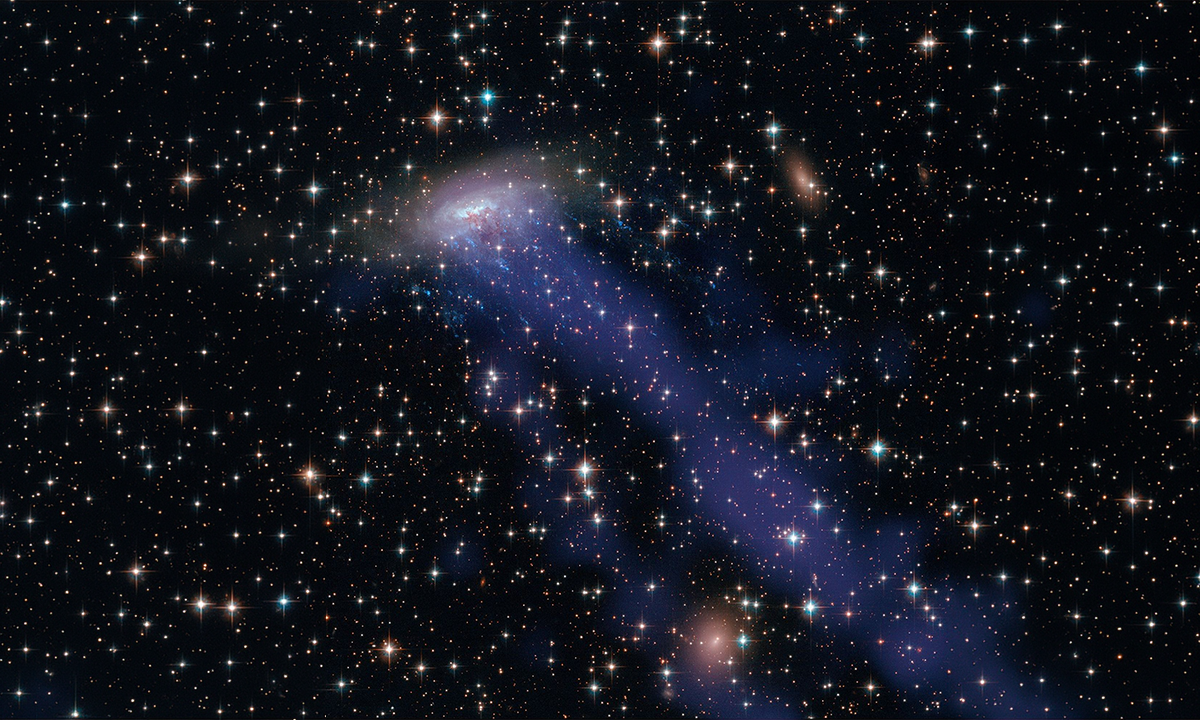

Until now, gas giant planets were a large missing piece of the puzzle. But in a recent paper, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Susan Mullally, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, in Maryland, and colleagues used the James Webb Space Telescope to find bright objects that are consistent with giant planets in two different systems, orbiting polluted white dwarf stars.

But, by accounting for the amount of mass loss during the earlier phases of stellar evolution, the first planet candidate would have been on an orbit around its host star almost identical in size to Jupiter’s around the sun. The other planet candidate would have started on an orbit very close in size to Saturn’s. Could these planets serve as analogs of Jupiter and Saturn, projected into the post-apocalyptic future in which the inner planets have been cannibalized by the sun, and our solar system is an all-but-forgotten frozen wasteland?

It’s not completely clear that the objects are truly gas giant planets; there is a very small chance that one or both could be a background object (such as a galaxy) that happens to line up very close to a white dwarf on the sky.

But the stories of these systems’ demise likely echo our solar system’s future. The two white dwarfs are somewhat more massive than our sun, meaning that they evolved faster. Each likely formed a rich planetary system, with at least one gas giant as well as populations of asteroids and probably rocky planets as well. The central stars evolved into red giants, then puffed off cosmic dust and gas, causing their planetary systems to expand and leave behind a white dwarf. Asteroids or comets (or even rocky planets) were surely tossed about by the giant planets’ gravity; some were likely shredded into debris that was pulled into the now-polluted white dwarfs.

In the coming years, other missing pieces of these tales of planetary destruction will be filled in. It remains to be seen whether white dwarf pollution is generally driven by gas giants, or if lower-mass planets (like Neptunes, which are more common as exoplanets) may play just as big of a role. It would also be very useful to see if any correlations exist between the type of pollution (rocky, icy, or other) and the nature of the planetary system orbiting a given white dwarf. The James Webb Space Telescope has already turned an important page in our understanding of these dramatic histories, and, with its unprecedented imaging capabilities, it could turn more.

A glimpse like this into the cosmic graveyard can help us appreciate what a special place our planet occupies, both in space and in time. Just like people, planetary systems are born, evolve—then die. It’s a good reminder that there’s no time like the present to make the most of this glorious-but-finite chapter in the solar system’s story. ![]()

Lead image: BetsyChe / Shutterstock