Along the bayous of Louisiana, south of New Orleans, five Native American settlements are clinging to disappearing earth. Their homes outline the narrow strips of land deposited by the Mississippi Delta like the fingers of a skeletal hand disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico.

Southeast Louisiana is losing this land at an alarming rate—approximately a football field of land every 100 minutes—mostly due to human impacts of oil and gas extraction, subsidence, sea level rise, and increasingly damaging hurricanes brought by climate change. The people who make their homes here are continually seeking and finding creative solutions. A role they’ve taken on for centuries.

Many can trace their roots in the area to the 18th and 19th centuries, when a small number of Choctaw, Chitimacha, and other Native Americans—including some of my maternal ancestors—survived the vagaries of colonial settlement, wars, and waves of Indian removal policies in the remote coastal marshes of southeast Louisiana.

Over generations, they formed unique communities descended from a handful of shared Native American ancestors who intermingled with French and other European settlers. Here they farmed, raised animals, trapped, fished, and grew into large families for generations—until massive coastal erosion began eating away at the land.

I have been photographing two of these communities, Isle de Jean Charles and Pointe-aux-Chenes, since 2005. In 2024, I returned to the project after a 12-year hiatus. In many cases, I ended up photographing the same location with more than a decade between each image.

Most of the residents of Isle de Jean Charles—which was featured in the 2012 film Beasts of the Southern Wild—have recently relocated together to a new community called New Isle, 33 miles farther inland. As a result, the community is far less inhabited now than it was when I last visited—I see plants and animals filling in the spaces that humans have vacated.

In this selection of photographs, I attempt to crystalize changes happening at both a geological and a human time scale so that they are more observable. The cycles of storm damage and recovery, erosion and displacement, are becoming more visible by the year. Developing relationships with people and landscape, I have come to see the fluid and powerful dynamics of loss and adaptability, the fragility and the strength of humans and a rapidly shifting ecosystem.

Left: January 2009

Sign at the entrance to Isle de Jean Charles.

Right: August 2024

Sign in front of a house on Island Road, Isle de Jean Charles.

Left: August 2010

Susie Danos in her garden on Isle de Jean Charles where she grew melons, cucumbers, beans, and okra. After years of storm flooding, some residents fear that the soil is contaminated by residue from offshore oil drilling. Frequent salt water intrusion kills plants and trees like the dead oak tree visible in the background.

Right: September 2024

The site of Susie Danos’ gardens in 2024, marked by alligator tracks in the mud left by Hurricane Florence in 2018. Susie has left the island to live with her daughter’s family farther inland.

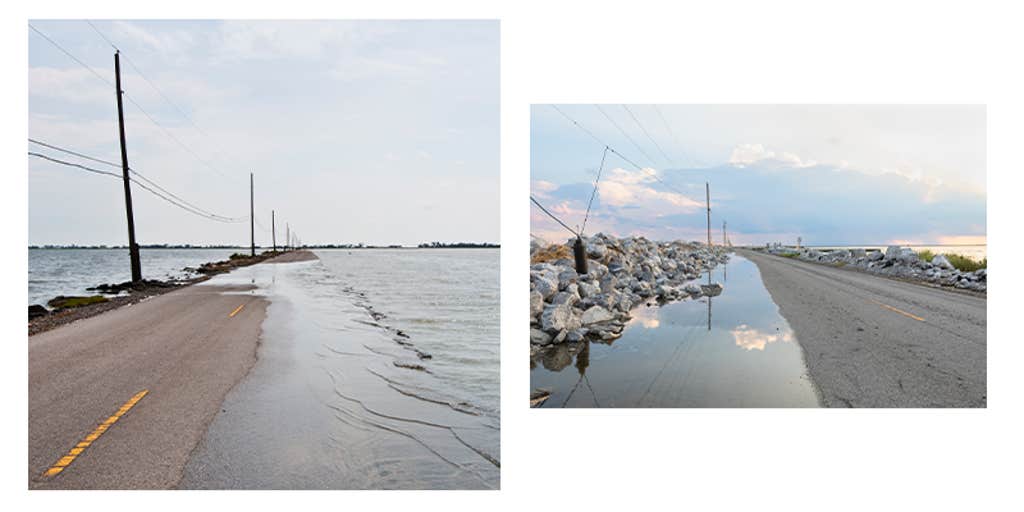

Left: September 2008

The single road that connects Point-aux-Chenes to Isle de Jean Charles. The road often floods and is in need of frequent repair due to coastal erosion.

Right: September 2024

The single road that connects Point-aux-Chenes to Isle de Jean Charles after Hurricane Francine, looking east. The road has been reinforced with riprap. Drainage pipes have been installed to allow water to recede after flooding.

Left: November 2009

Edison Dardar, Sr. on his porch in Isle de Jean Charles pictured after flooding receded from the island. Dardar cast for shrimp with a net nearly every day, just a few hundred meters from his house. He was vocal about not wanting to live anywhere other than his home on Isle de Jean Charles.

Right: September 2024

The house of Edison Dardar, Sr. on Isle de Jean Charles pictured after Hurricane Francine hit this year. Dardar died in December 2023 at age 74. He never left his island home.

Left: January 2010

A dead oak tree, known as a “skeleton tree” en route to Isle de Jean Charles and Pointe-aux-Chenes. Dead oak trees are a common sight along the eroding coastline of Louisiana. As salt water encroaches, trees and other fresh water flora are dying.

Right: August 2024

The same tree. ![]()

Lead photo by Kael Alford / Panos Pictures