Over the weekend, a bomb cyclone is forecast to hit the Southeast United States. This prediction follows a week of bitter cold for most of the country and record-breaking snowfall in some areas, including New York City and Dayton, Ohio.

Bomb cyclones—formally referred to as bombogenesis—are quickly strengthening storms that brew at mid-latitudes. They kick up when a storm’s central pressure falls by a certain number of millibars in 24 hours, depending on the location. They can form when cold air masses smash into warm ones; for example, in the Northeast they often occur when cold air from Canada runs into the toastier Gulf Stream.

Bomb cyclones can spark intense winds that whip at more than 80 miles per hour and heavy rain or snow, and they typically form between October and March due to dramatic temperature contrasts during the colder months. Many nor’easters are bomb cyclones, and these tend to crop up in the latitudes between Georgia and New Jersey before reaching their peak around New England and parts of Canada.

“If you’re watching TV at night and the weather report comes on and you’re hearing ‘bomb cyclone’ being used, that usually means there’s quite a bit of active weather going on,” Andrew Orrison, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in College Park, Maryland, told The Associated Press.

Read more: “The Grand Collisions That Make Snownadoes & Arctic Sea Smoke”

Bomb cyclones aren’t too common—they made up around 7 percent of all nontropical low-pressure systems near North America between 1979 and 2019, an average of some 18 per year over that time period. They’re most prevalent along the East Coast.

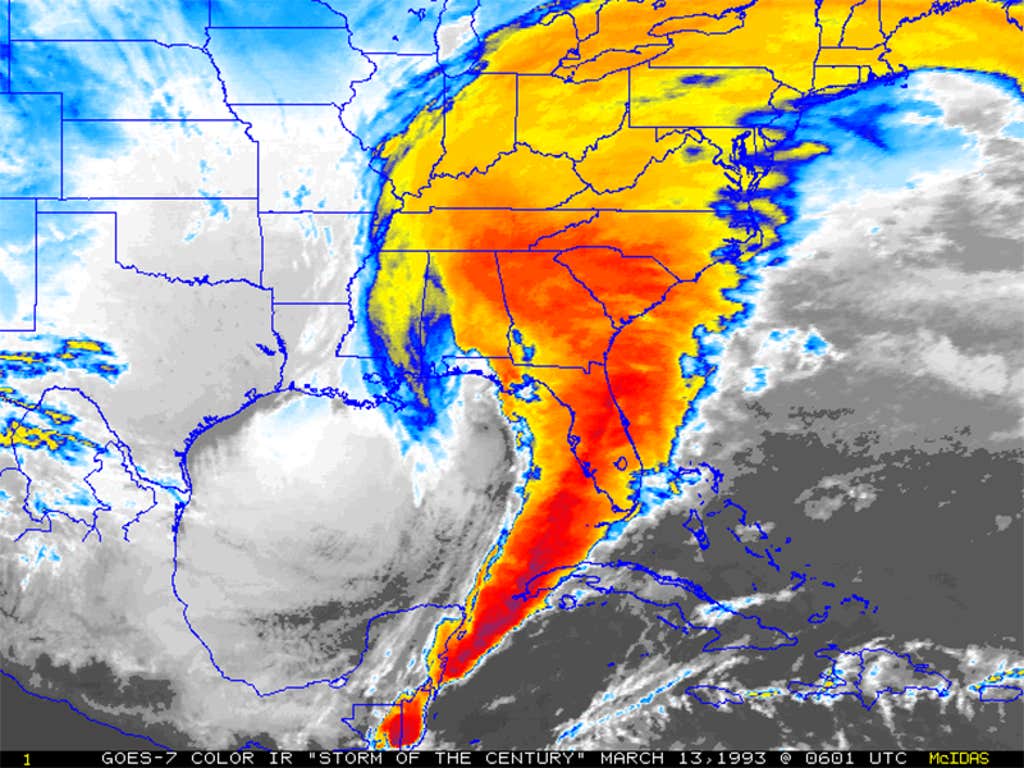

Among the deadliest nor’easters arrived in March 1993, known as the Storm of the Century. It barreled from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada and killed more than 250 people in its wake. The storm started as a low-pressure system and picked up as it traveled north. It brought all sorts of nasty weather, including winds up to 144 miles per hour, blizzard conditions, and even tornadoes in some areas. Every major airport and interstate highway along the coast shuttered at some point during the nor’easter, and millions of people lost power.

Like other weather phenomena, scientists think that climate change is intensifying nor’easters—this is probably due to rising ocean temperatures and the warming atmosphere’s ability to hold more moisture. Researchers found that nor’easter precipitation rates increased between 1940 and 2025, and they also noticed an upward trend in the maximum wind speed of the strongest of these storms—so that portion of the country can likely expect more wild winter weather in the years ahead. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: brian.gratwicke / Wikimedia Commons