The groundbreaking finding that enables doctors to peek inside our bodies and astronomers to probe the mysteries of space was announced on this day, 129 years ago.

Wilhelm Röntgen, a German physicist, accidentally discovered the X-ray in 1895 while tinkering in his lab. At the time, scientists were fascinated by the then-elusive dynamics of electricity. Röntgen had wondered whether streams of electrons called cathode rays—produced in charged glass containers called cathode tubes—could move through glass.

He had covered his cathode tube in heavy black cardboard, but he noticed that a green glow seeped through and projected onto a fluorescent screen in his lab. This odd phenomenon persisted even when the receiving surface was more than 6 feet away from the tube.

Wilhelm Röntgen/Old Moonraker/Wikimedia Commons.

Röntgen beamed the rays through items of varying thickness and observed that they showed different degrees of transparency to this light when recorded on a photographic plate. He named them X-rays, with X referring to “unknown.”

On January 5, 1896, the Austrian newspaper Die Presse broke the news of this revelation. The article “was composed hastily by the editor in a journalistic style and contained no information on the nature of the new rays,” according to a paper published in the Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. Two days later, however, Die Presse ran another article with more details on the finding.

Read more: “Discovering the Expected”

Not long after his initial X-ray experiments, Röntgen learned that his rays could travel through human tissue to illuminate the bones within. He captured the bones in the hand of his wife, Anna Bertha Ludwig. “I have seen my death,” she said at the time. Röntgen noticed that the skin around her bones had a fainter shadow because it was more permeable to the rays

In later experiments, German physicist Max von Laue and his students demonstrated that X-rays “are of the same electromagnetic nature as light, but differ from it only in the higher frequency of their vibration,” according to the Nobel Prize organization.

Within a year of Röntgen’s initial eureka moment, doctors in the United States and Europe incorporated the new-fangled technique into their work. In 1901, Röntgen received the inaugural Nobel prize in physics, among other awards, and several cities named streets after him. Still, he “retained the characteristic of a strikingly modest and reticent man,” the Nobel Prize organization notes. In fact, Röntgen never applied for patents and said that “his inventions and discoveries should belong to humanity. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

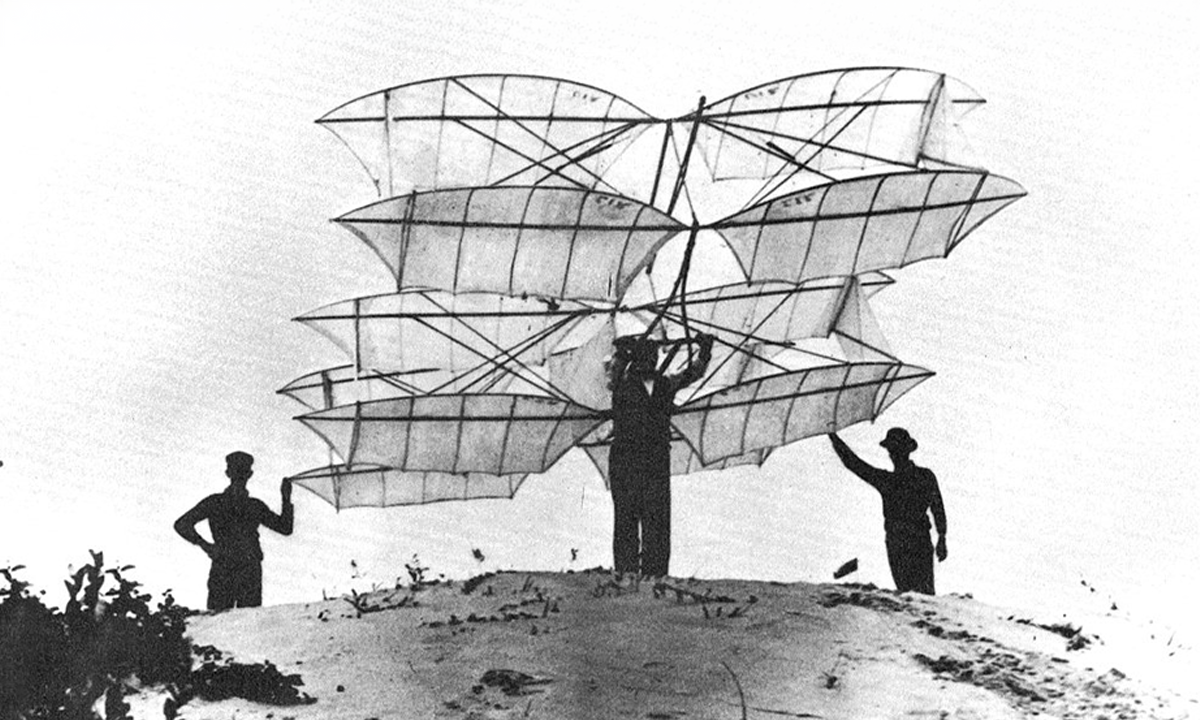

Lead image: Internet Archive Book Images / Wikimedia Commons