If you take a close look at the pottery bearing some of the oldest known plant art, you can find the buds of mathematics—advancements that seem to have emerged millennia before the invention of writing or formal numeric systems.

It’s difficult to track humanity’s development of mathematical skills before writing or numbers came onto the scene, but art can offer some promising hints. Early ancient art mostly consisted of relatively straightforward depictions of animals and humans, but later works represent a critical shift in which people began to exhibit more complex visual flair and an increasing grasp of geometry.

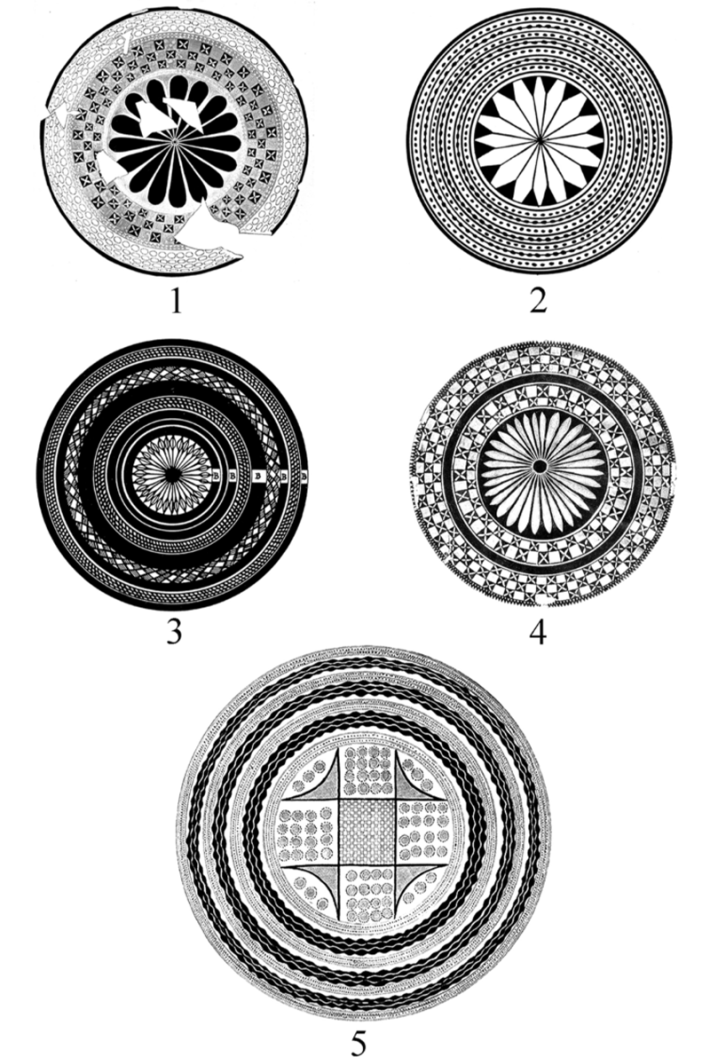

This includes sophisticated pottery from the Halafian culture of northern Mesopotamia, a society of farmers. A team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel analyzed ancient botanic illustrations found on Halafian pottery from 29 archeological sites spanning 6200 to 5500 B.C. to learn more about these floral findings.

“These vessels represent the first moment in history when people chose to portray the botanical world as a subject worthy of artistic attention,” the study authors, Hebrew University archeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich, said in a statement. “It reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics.”

By closely inspecting more than 700 pottery fragments adorned with plant motifs, Garfinkel and Krulwich noticed a fascinating pattern: They found floral bowls with petals arranged into geometric sequences of 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64, findings reported in the Journal of World Prehistory.

Read more: “Finding the Color of an Empire”

“The ability to divide space evenly, reflected in these floral motifs, likely had practical roots in daily life, such as sharing harvests or allocating communal fields,” Garfinkel added.

This suggests that these pieces of pottery were more than pretty possessions—they helped people make sense of their surroundings and think through complicated tasks. This unfolded thousands of years before the world’s first known writing system, cuneiform, emerged in Mesopotamia around 3000 B.C.

“These patterns show that mathematical thinking began long before writing,” Krulwich said. “People visualized divisions, sequences, and balance through their art.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) / Wikimedia Commons