Before there was writing, humans had craft. And through that craft, empires learned they could communicate their reach—even through something as nuanced as the shade of a color.

One imperial hue has retained a sort of impact for more than a millennium, pulling a Peruvian archeologist to search for the source of its influence. The particular shade of black on pottery created during the Wari empire (roughly 600 to 1050 A.D.) in what is now Peru, Louis Muro Ynoñán learned, tells an unexpected story of creation and power.

The Wari (the largest empire in South America prior to the Inka) expanded their reach from a central valley to the coast and across the rugged terrain of the central Andes, up north to near the current-day border with Ecuador and south to near that of current-day Chile, bringing local populations into their expanding folds. Pottery from this empire is often covered with thick-lined figures and vibrant yellow, red, green, orange, and other colors.

But there was something, specifically, about the black on these objects that captivated Ynoñán when he was a young student in Peru. He confides that he became a bit “obsessed” with that consistently deep, rich shade in these ancient vessels. Then, when Ynoñán (now a postdoctoral researcher at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art) was a research associate and postdoctoral scientist at the Field Museum, he had the opportunity to discover its secret power.

The secret, it turns out, is manganese. He and his colleagues sampled pigments from Wari vessels made between 600 and 900 A.D. unearthed from several sites at locations from the north and south of the empire. They found, as they described in a Journal of Archeological Science: Reports paper in March, that most pigments were created from locally sourced materials. But the black was made with the element manganese, replacing earlier local traditions that had used calcium or iron in their black pigments, suggesting it was coming centrally, from the empire itself. (A second study, published in the same issue of the journal, used lasers and other chemical analysis to confirm that pottery was made locally, rather than imported from the Wari capital, as many cultural goods were in other empires.)

Ynoñán and his colleagues describe the result as a certain “Wari experience of color.” And, he says, “those colors have a very potent, powerful meaning.”

The findings suggest that local populations were “not only controlled through an economic relationship, but also an ideological relationship,” Ynoñán says. “There was no writing mechanism for writing records to control or impose rules,” he says. “Most of the [imperial] interaction was actually created through these objects. These objects are in charge of political leanings … Through the color, these communities are actually showing their affiliation with the super-powerful elite”—while also retaining a visual connection to their local traditions, creating a sort of nuanced, hybrid cultural message, Ynoñán says.

The potter, it turns out, is political. ![]()

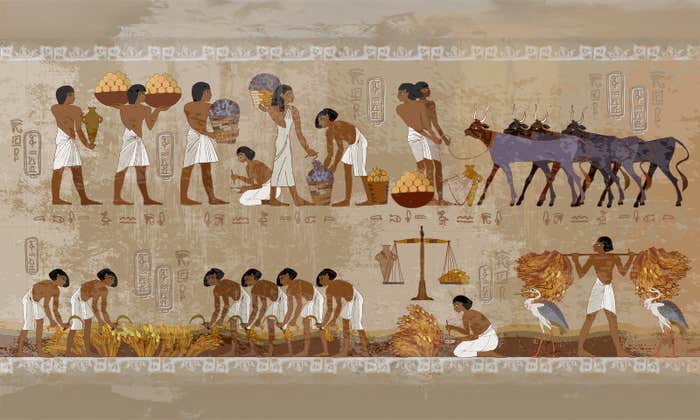

Lead photo courtesy of the Field Museum anthropology collections.