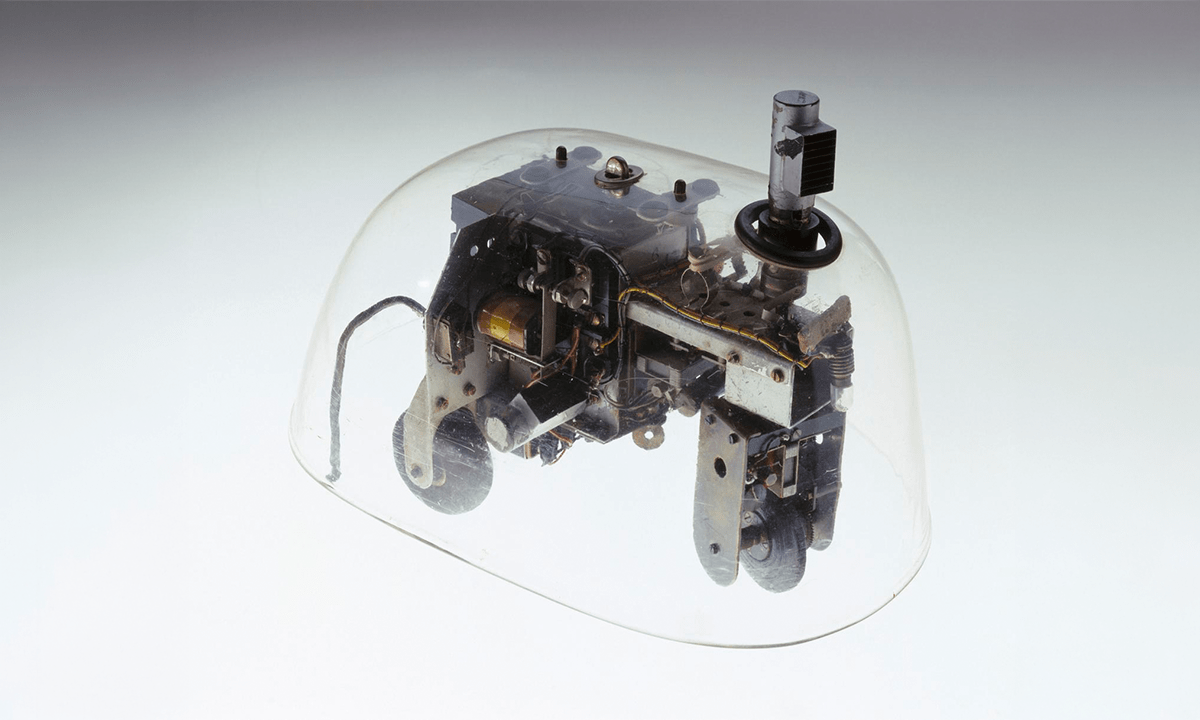

Nearly 70 years ago today, nuclear fission at the country’s first full-scale commercial nuclear power plant became self-sustaining and primed to power homes and businesses. This energy milestone arrived exactly 15 years after the first such nuclear chain reaction triggered by humans, a key Manhattan Project feat that paved the way for the atomic bomb.

The Shippingport Atomic Power Plant, located in Pennsylvania, reached its full generating capacity a few weeks later, on Dec. 23, 1957, around three years after the Soviet Union launched the world’s first grid-connected nuclear power plant. The United States plant fit into President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vision of wielding nuclear technology not for war, but to benefit humanity in peacetime. “Through knowledge we are sure to gain from this new plant we begin today, I am confident that the atom will not be devoted exclusively to the destruction of man, but will be his mighty servant and tireless benefactor,” Eisenhower said at the plant’s groundbreaking ceremony.

While providing electricity to people throughout the Pittsburgh area, Shippingport also allowed scientists to experiment with various kinds of cores, the central parts of nuclear reactors that contain the fuel required to vaporize water. That steam then spins a turbine to generate electricity. For example, the reactor’s core was swapped in 1977 for a light water breeder reactor, which contains both uranium and thorium—a cheaper, more easily accessible element than the former.

Read more: “The Road Less Traveled to Fusion Energy”

Shippingport went offline in 1982, a few years after an incident that contributed to the decline of the budding U.S. nuclear energy boom. On March 28, 1979, part of the core melted in a reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear power station in Pennsylvania. The accident fomented concern among the U.S. public, which feared another disaster. The nuclear industry also faced major financial woes at the time: Beginning in the mid-1970s, a flurry of new reactor projects slated to wrap up quickly were abandoned after construction delays and budget issues.

Shippingport’s demise raised another nuclear dilemma that still begs solving: Where does all that spent, radioactive fuel go? Once the radioactive elements in the core have degraded to a certain level, they are no longer energetic enough to generate steam and turn turbines. They must be replaced, but the used up waste continues to emit radioactivity for millennia.

Ultimately, the Shippingport reactor was shipped around the world—down the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and through the Panama Canal, finally ending up in Washington State. The reactor was buried at the Hanford Military Reservation, and Shippingport’s fate was hailed as a successful example for future decommissioning projects.

Over the past few decades, only a handful of new nuclear reactors have been built in the U.S., and the country’s operational reactors are around 40 years old, on average—yet they still manage to supply some 20 percent of the country’s total electricity.

Now, data centers have thrust nuclear energy back into the spotlight. To support the ballooning energy demands posed by AI, tech giants are turning to energy sources that aren’t reliant on fossil fuels, like nuclear. For example, the Department of Energy recently announced a $1 billion loan to build a nuclear plant on Three Mile Island that’s planned to power Microsoft data centers in the area.

Even if such projects are successful, the nuclear waste issue still looms. In the 1980s, the Department of Energy eyed Yucca Mountain in Nevada as a potential site to store spent fuel deep underground, but the project has run into barriers such as fierce opposition from the state of Nevada and Congressional funding cuts. For now, about 90,000 tons of nuclear waste sits at more than 100 sites in 39 states.

Data centers might only add to this growing collection of hazardous byproducts, forcing officials and energy industry leaders to find a more-sustainable, long-term solution. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: metamorworks / Shutterstock