There’s a mystery lurking on the dusty surface of the moon, one that was uncovered during the first Apollo missions—particles from Earth, including water, found in lunar soil. Now, scientists think they may have cracked the case of how they got there.

Studying the first samples of moon dust (also known as “regolith”) from the Apollo missions, scientists discovered curious traces of water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen. Some of these elements may have been pushed to the moon from Earth by solar winds, but the high levels of others, such as nitrogen, puzzled researchers. How did particles from Earth’s atmosphere end up on the moon?

A team led by scientists from the University of Tokyo offered a possible explanation in 2005. The particles escaped Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago, the scientists said, due in part to our young planet’s weak magnetic field. However, research into iron-rich rocks unearthed in Greenland has since shown Earth’s magnetic field was just as strong 3.7 billion years ago as it is today.

Read more: “The Moon Smells Like Gunpowder”

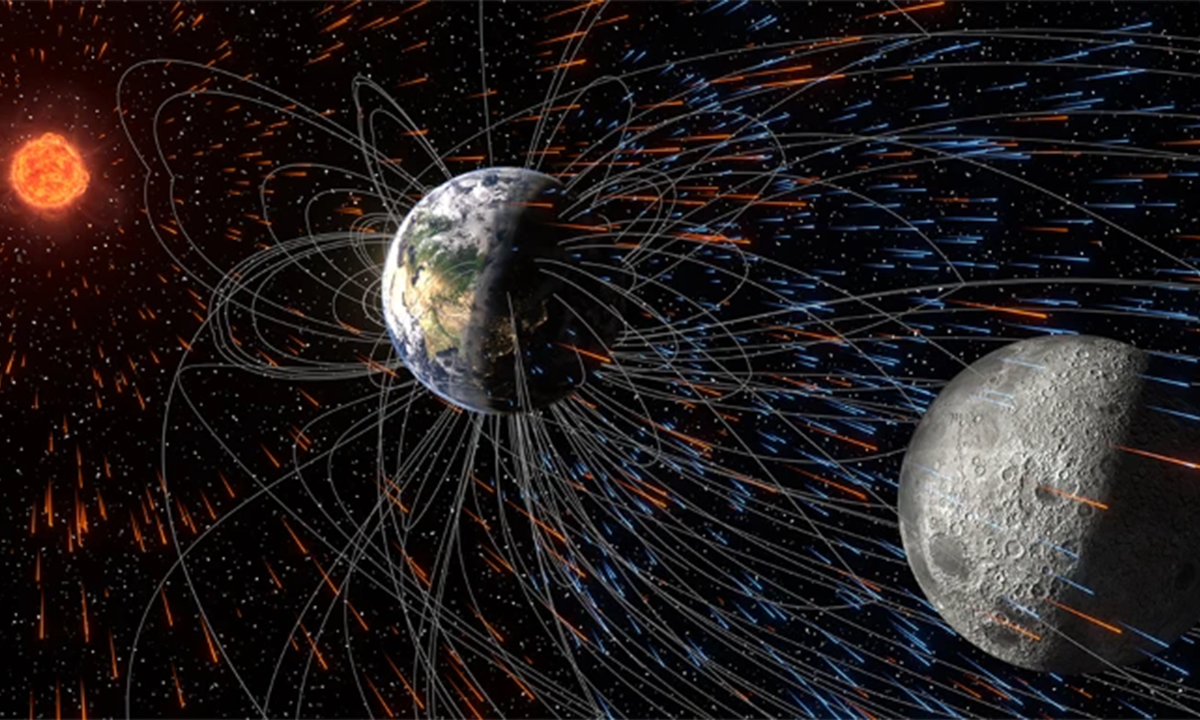

Now, new research from the University of Rochester, published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment has posited a possible answer. By combining data from regolith samples, solar wind, and Earth’s magnetic field, scientists devised computer simulations to test two different scenarios: An “early Earth” model featuring a weak magnetic field and a strong solar wind, and a “modern Earth” model featuring a strong magnetic field and a weak solar wind.

Surprisingly, the modern Earth scenario proved to be the best match for the particle levels in lunar regolith. But why? Scientists believe that once charged particles were knocked loose by solar wind, Earth’s magnetic field acted as a kind of guide, transporting them to the moon like a cosmic conveyor belt.

This new finding has important implications for both our own planet and our hopes to colonize others. First, the long-term particle transfer between the Earth and our moon means there could be a record of our planet’s early atmosphere deposited in lunar regolith. Secondly, the presence of water and other elements conducive to life could lower the barrier to developing a human presence on the moon and beyond.

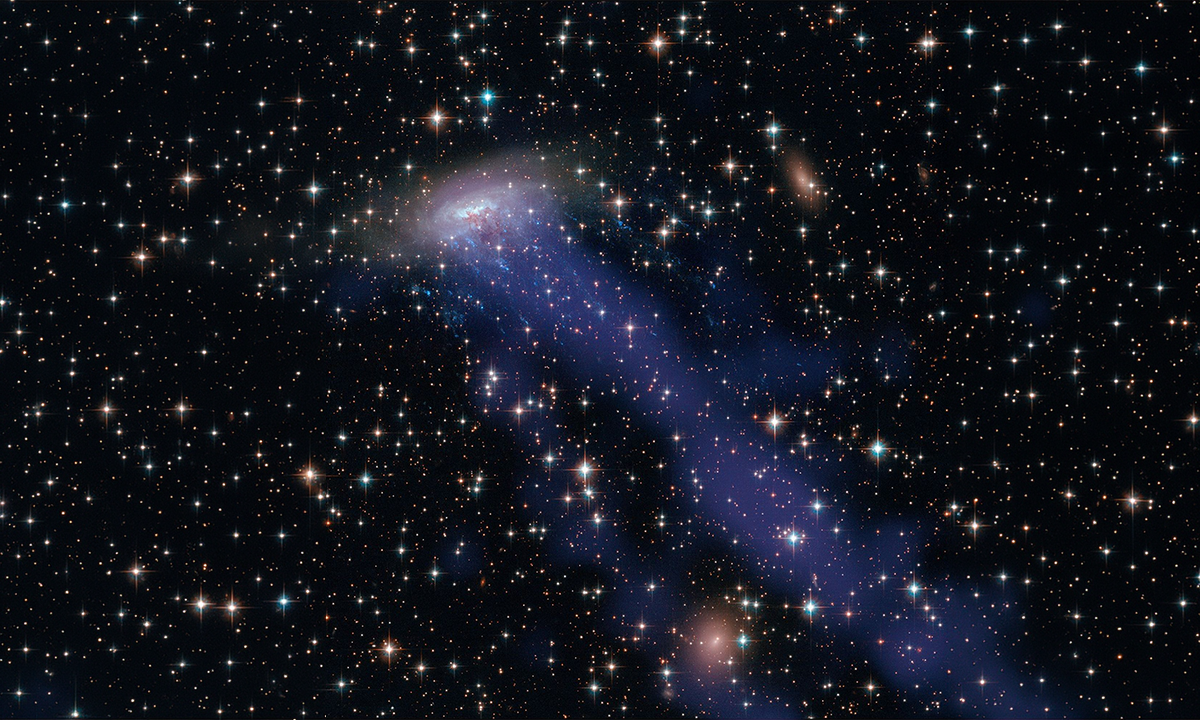

“Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past, along with a likely thicker atmosphere,” study co-author Shubhonkar Paramanick, an astrophysics graduate student at the University of Rochester, said in a statement. “By examining planetary evolution alongside atmospheric escape across different epochs, we can gain insight into how these processes shape planetary habitability.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: University of Rochester / Shubhonkar Paramanick