At the end of the smash Broadway musical, The Book of Mormon, the protagonist, Elder Price, a zealous young Mormon missionary in Uganda, triumphantly sings, “We are still Latter day Saints, all of us / Even if we change some things, or we break the rules.”

The ribald musical, written by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, mocks the Mormon religion and its visionary founder Joseph Smith. At one point Smith has sex with a frog to rid himself of AIDS. The musical gleefully incorporates how the real church will react to it, having an outraged Mormon leader, Mission President, declare, “You have all brought ridicule down onto the Latter Day Saints!”

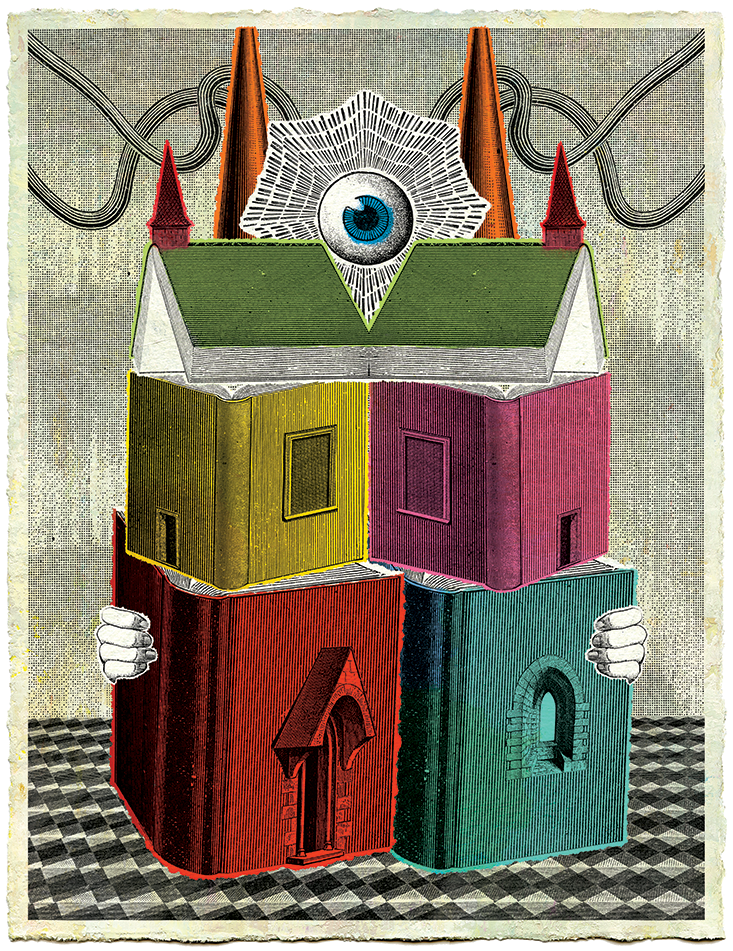

If the real Mormons feel like Mission President, they aren’t showing it. Instead the church has consistently bought ad space in cities where the musical has appeared to promote the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the real Book of Mormon, its sacred foundation. The ads have appeared on a Times Square billboard, around London, and in The Book of Mormon playbills for touring companies, featuring the taglines, “You’ve seen the play… now read the book,” and “The book is always better.”

Clearly the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can take a joke—especially if it gets people talking about the faith. That the Mormon church appears to be good-natured about a scatological musical might surprise those who associate the church with the squeaky clean image of the Osmond family and Mitt Romney.

Religions don’t have literal DNA, of course, but they can parallel how species mutate.

The truth is that the Mormon church has always changed with the times. Religions have to mutate “if they’re going to survive,” says J. Gordon Melton, a religious scholar who founded the Institute for the Study of American Religion. They survive by setting what the anthropologist Roy Rappaport has called “ultimate sacred postulates,” ultimate truths, and then re-interpreting them over time. Scholars say the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints provides a casebook study of how a religion has thrived by folding its postulates into a social institution that adapts to changing environments.

The analogy, they say, can be stretched to science. Religions don’t have literal DNA, of course, but they can parallel how species mutate. There are key properties of successful genetic mutations that religions must have to succeed, says Lucas Mix, a researcher at the Haig Lab at Harvard University, who is both an evolutionary biologist and an Episcopalian priest. The properties are inheritance, variation, and selection.

For religions, inheritance means the ability to transmit beliefs, behaviors, and a sense of belonging to new generations. Variation means having the ability to allow for innovations to take place, and selection means having a way to absorb converts and deal with bad mutations, in religion’s case apostates or heretics. Because Mormonism emerged so recently, says Jan Shipps, a historian of Mormonism, we can see its changes and how they helped guarantee the church’s survival and growth—in fact, its phenomenal growth. Sociologist Rodney Stark, co-director of Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion, has projected that 265 million Mormons will populate the world by 2080.

The Mormon story is quintessentially American. “It has all the features we associate with being American: patriotism, country, entrepreneurship, capitalism, all bound together,” says Wade Clark Roof, professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Mormon founder Joseph Smith was born in Sharon, Vermont, in 1805. The Louisiana Purchase was barely two years old. The westernmost of the 18 U.S. states were Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio. Florida, what would become Texas, California, and Utah, were all Spanish possessions. The U.S. had thrown off its connection to English and European history. The nation, whose population would triple during Smith’s 39 years, was pushing west into new territories. Smith’s family would itself move to Palmyra in western New York by 1817, seeking economic opportunity as the Erie Canal was being built.

The Smiths moved into the heart of the Second Great Awakening, a period of intense evangelization that ran from about 1790 until the end of the 1830s. Western New York was dubbed the Burned-Over District because so many people, the saying goes, were burned by the fires of revivalism. It was here, in 1827, that Smith claimed to have been led by the angel Moroni (son of the prophet Mormon) to gold plates written in “Reformed Egyptian.” He spent the next three years “translating” the plates through a series of visions, dictating what he was told to various scribes.

The Book of Mormon did not replace what Christians call the Old and New Testaments, but became “another testament of Jesus Christ,” written as “a record of God’s dealings with the ancient inhabitants of the Americas and contains, as does the Bible, the fullness of the everlasting gospel.” Perhaps most pivotally, at least in connecting the new religion to the new nation, the Book of Mormon claimed that Jesus, shortly after his resurrection, descended from heaven into America to heal the sick, bless children, and teach disciples how to spread his gospel.

Being able to change without having practitioners feel like they have changed is a powerful adaptive tool for religions.

The Book of Mormon was published in 1830, and from six initial converts, Mormonism grew quickly, thanks in no small part to Smith’s charisma, touting the Book of Mormon like a talisman. Soon he had to build a more formal structure for his religion, and his vision of a new heavenly society on Earth. He called the faithful to a central location, a trait of Smith’s Mormonism that probably helped it in the beginning, notes Matthew Bowman in his 2012 book, The Mormon People. Smith sent out evangelists, including to England and Scandinavia, but encouraged converts to come to where he was and settle, a community that could be separate from those who disagreed with their radical new ideas.

It was not free from strife. Smith had to flee his base in Kirtland, Ohio, due to the crash of a bank he founded, heading to Missouri, where a successful Mormon outpost had been established. The Mormons’ rapid growth upset the settlers there, and armed conflict broke out. Smith was jailed along with some other Mormon leaders, released after the Mormon community had gone across the Mississippi River into southern Illinois. They established Nauvoo, which grew to 12,000 residents by 1844, the largest settlement in Illinois, more than twice the size of Chicago. Troubles came there, as well, in part because it became public knowledge that Smith was practicing polygamy. Smith attempted to destroy a local newspaper that exposed the polygamy, caused a public riot, and was jailed. A mob stormed the jail and killed him and one of his brothers.

The death of the prophet shocked Mormonism. But it survived because Smith had put in place mechanisms to accept and reject innovations, mechanisms that allowed it to both adapt and wall off competition. Smith established multiple councils, like the First Presidency, the Quorum of Twelve, and the Seventy, to judge new ideas, and he himself was subject to the councils. This helped Smith, and Mormonism, to contain the excitement of other newly converted Mormons, who were prone to charismatic visions of their own. It also meant there was established leadership in place to guide the church after Smith was killed; though some groups of Mormons split off, most remained supporters of Brigham Young, the leader of the Quorum of Twelve eventually elected as Smith’s successor. This leadership structure remains in place today.

The church’s prime mutation was the Book of Mormon itself. “A lot of religions tend to last as long as the prophet, and when the prophet dies, the religion itself begins to die out,” says Shipps. “The important thing about Mormonism is that it has the Book of Mormon.”

The stories within the Book of Mormon offered a new revelation about Christianity, one adapted specifically to America. Those who accepted the message could believe they were helping to restore the real church of Jesus Christ, a seductive message. Mormonism is built on “a narrative structure rather than a philosophical belief system,” explains Kathleen Flake, professor of Mormon Studies at the University of Virginia. “That allows people to find meaning in it through narratives.” It allows them to see God’s impact on their own lives.

The properties are inheritance, variation, and selection.

Flake explains the church has simplified its message as the church has spread, a subtle adaptation most Mormons may not notice. Sunday school lessons involve simply giving scriptures to read and having people discuss them in their local context, without theological takeaways. Borrowing from existing successes, the centralized structure for controlling doctrine resembles that of the Catholic Church. Mormon men are even designated priests, but don’t take vows of celibacy or spend years in theological training. The Latter-day Saints do not have a seminary. At the local level, every one is a volunteer, and every person has a role to play.

As the 19th century rolled on, the Mormons adapted their doctrines to ensure their survival multiple times after Brigham Young led them west into what was then Mexico. He went seeking a place to create a new Israel, a heavenly kingdom on Earth, with its own laws, an idea that attracted Mormon converts looking to be part of something important. But Utah was not very hospitable, and Young would seek federal money for his struggling flock, creating ongoing tensions between the Mormons and the American government, especially after the Mexican-American War ceded territory including Utah to the U.S.

The Mormons lived communally, until the railroad and non-Mormon settlers forced them out of isolation. While a minority of Mormons practiced polygamy, the leadership fought to keep it, arguing it was protected as freedom of religion, until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the practice. While the church was under public fire, it steeled itself with capitalist enterprises. Young set up department stores and a co-op mercantile institution. “A mercantile church and a missionary church move in the same holy direction, and the vector that points both forward is the energy of enterprise,” wrote Adam Gopnik in a 2012 New Yorker essay on Mormonism, as Romney ran for the White House. “It was a victory of Gilded Age capitalism … over Great Awakening spiritualism.” And one that would stretch into the 20th century. Some of the major companies started or run by Mormons include Marriott, the hotel chain, JetBlue and Skywest airlines, Bonneville Distribution, and Beneficial Life Insurance.

It’s a hallmark of religions to claim they haven’t changed significantly in their core beliefs. Yet being able to change without having practitioners feel like they have changed is a powerful adaptive tool for religions, says Richard Sosis, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, and co-editor of the journal, Religion, Brain & Behavior. “Religion’s sleight of hand is fascinating, how effective religions are at masking the change that takes place,” he says. Scholars “often recognize these changes as a consequence of economics and politics and all the different sociopolitical factors we would anticipate religion adapting to. But within the religion, you don’t experience them.”

Religions stress continuity to avoid appearing expedient, Sosis says, and to preserve their connection to the sacred, to the things that made them important in the first place. Religions want to stay connected to the sacred aspects that infused their founding and development. Rituals tend to endure, while behaviors adapt to social norms; a choir may be accompanied by a five-piece band instead of an organ, playing a modern hymn, but it’s still a hymn.

Mormonism, then, has adapted in part by adopting a structure that allows for local flexibility and requires local involvement, which encourages members to be more involved. This allows the religion to mesh with many different cultures. It has a prophet who declared new core truths to an existing religion and published the basis for those. It has always encouraged missionaries to go out and spread word of its beliefs, drawing in new people.

The Mormons “are notoriously one of the most assertively proselytizing churches,” Flake says. “Mormons fly whatever flag gives them the freedom they need to root that religion in their culture. They root it by observing the culture laws of that country.”

But the Mormon structure, like those of many religions, looks backward, not forward. It is not a structure that allows for quick responses to social currents. As Flake notes, two of the three major social movements in America and much of the world in the last 100 years include equal status for women and gays and lesbians. The Mormons are among many religions that do not give full equality to women, gays, and lesbians.

Such stances make Mormonism seem regressive in the U.S., where in a recent poll 55 percent of Americans support gay marriage, and where women have gained full leadership roles in a number of churches, notably Protestant denominations.

The real Mormon church has consistently bought ad space in cities where The Book of Mormon has appeared to promote itself.

Social pressure will not change the church. Outsiders and dissenting Mormons can feel anger about the church’s practices, but there’s little point to organizing protests. The President of the Church, in accord with the two other members of the office of the First Presidency and the 12-man Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, changes doctrine. Flake says this creates incredible stability and immunity from outside influences or charismatic mavericks. The Mormons “pay a price for it but they also get a benefit for it,” says Flake. “The price and the benefit look remarkably alike. You constrain or stabilize the system. It also makes them a very structurally conservative institution. They have to move by agreement.”

That need for concurrence makes Mormonism a religion that is not typically subject to disruptive innovations, to borrow a term from Clayton M. Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School, an expert on innovation and a Mormon. In an interview, Christensen, 62, says the church is different than the church of his youth—it ordains blacks and sends more women on missions. It’s because “we remain open to questions,” he says, as Mormon Tabernacle Choir music plays in his office. He argues that other religions prefer to say they have all the answers. Practitioners of other faiths might dispute this, but new prophecies tend to be viewed with skepticism. Mormonism considers itself a faith of continuous revelation, where God may give new prophecies to the church’s leadership. That gives it a mechanism for doctrinal change, such as abandoning polygamy or opening the priesthood to non-whites.

Christensen tells a story from the Book of Mormon about the brother of Jared, an ancient prophet, who talked to God in the clouds. God instructed the brother of Jared to build a boat and when he did, the brother asked God to imbue a host of white stones with light so the brother could place them in the dark hull of the boat to see. God agreed and the brother was “blown out of his socks with fear,” says Christensen, when he saw the actual finger of God, who later appeared to him as a man. The story, Christensen says, shows that while God doesn’t change, what people on earth can know about God can.

Christensen says this process is similar to what the church is going through on some social issues. “Our understanding of God, and our relation to him, and questions like same-sex attraction and marriage, we’re somewhere between here and there.” Christensen says he realizes that same-sex attraction and marriage can be seen as a disorder and a sin. (The church states “sexual relations are proper only between a man and a woman who are legally and lawfully wedded as husband and wife.”) But even if his position were that church leaders were wrong,1 Christensen says, “I can’t announce to mankind that I’m right and the church is wrong. The best I can do is to say, ‘well, just like the brother of Jared, where the truth is on the other side of this boulder, I’m on this side, I’m learning and I can say to myself and to my friends, I think I’m farther along than the church is on this one.’ ”

The church may catch up to society in its own time. Shipps notes in her 1985 book Mormonism that 1980s Mormons put back into 1880s Utah would not have recognized much about their faith, and the same may well hold true 100 years from now. As Mormonism continues to grow more rapidly outside the U.S. than in it, the religion will inevitably change. Already, its Quorums of the Seventy (there are eight quorums in total) includes numerous people born outside of the U.S., especially Latin Americans.

On a recent Sunday morning in Providence, Rhode Island, a new face of Mormonism, in tune with a changing America, is on display, underscoring the church’s perpetual ability to mutate and adapt. Music throbs happily as women in colorful dresses and men in suits and ties filter into a Mormon church in a well-kept red brick former school building.

“Buenos dias!” says a man in a light-colored suit, once black hair mostly gray. Behind him hangs a painting. Two robed gray-haired men, blatantly gringo, stand over a white boy who cowers on the ground before them. That boy is Joseph Smith. Smith did not speak Spanish. But his 1820 vision of God and Jesus telling him not to join any local church because religion had lost its way appears to mean as much to the members of this Spanish-speaking Mormon congregation as it did to him.

After Communion is served, Rich Hutchins, a Pfizer senior director, and volunteer Mormon stake president, stands at the church’s lectern. He’s tall, wearing an Organization Man gray suit and white shirt, his brown hair trim, his face clean-shaven, his back straight. He gives the sermon in fluent Spanish. His sermon is about splitting the congregation, sending those who live around Central Falls, a suburb north of Providence that is nearly half Latino, to worship in a different church.

“This is how to hasten the work of salvation in our stake,” he says, “it will enable more to attend church and worship.” As a young girl in a back row weeps, Hutchins exhorts the congregation to think of those they know who have stopped coming because it is difficult to get to this Providence church. “Invite back those who have gone away!” he tells them. “The Lord has given us an opportunity to save their lives.”

Michael Fitzgerald is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose work has appeared in The Economist, Fast Company, and The New York Times.