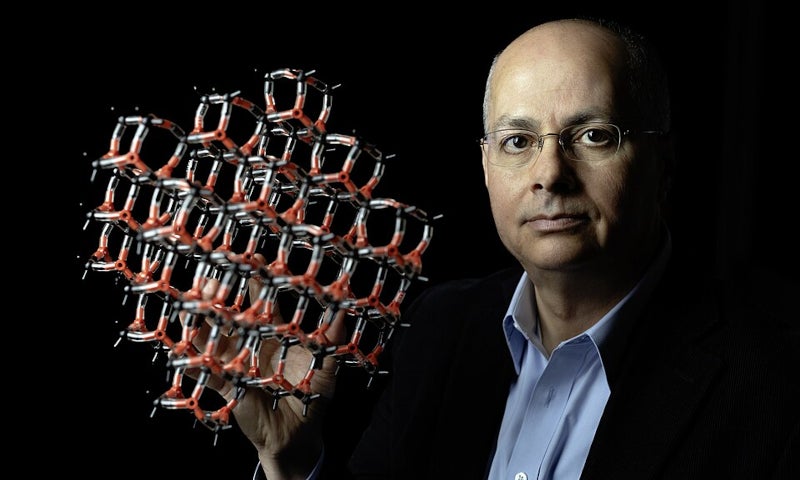

Growing up, Omar Yaghi shared a room with his siblings—and some cattle—in Amman, Jordan, with no access to running water or electricity. The son of Palestinian refugees who “could barely read or write,” the University of California, Berkeley, researcher was captivated by chemistry at a young age after gazing at “stick and ball” models of molecules in a library. This week, Yaghi received a share of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on revolutionary materials called metal-organic frameworks.

Yaghi moved to the United States at 15 years old, initially attending community college and eventually receiving his Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His path isn’t unique: Half of this year’s United States Nobel Prize winners in science are immigrants. Researchers with stories similar to Yaghi’s have propelled the country’s global scientific ascendance for generations. But with the increasingly restrictive immigration policies and science funding austerity enacted by the administration of President Donald Trump, the country’s top research rank—and future Nobel wins—hangs in the balance.

“The Trump administration is systematically discouraging international students and undercutting the research infrastructure that attracts them,” says James Witte, professor emeritus at George Mason University and former director of its Institute for Immigration Research. “Those students will find their academic homes elsewhere.”

“I think we will definitely see a long-run decline in U.S. science overall—measured by Nobel laureates.”

The U.S. wasn’t always the academic powerhouse it is today. Prior to World War II, Nobel laureates mostly hailed from European institutions—before the 1930s, scholars affiliated with U.S. institutions received less than 12 percent of all science Nobel Prizes. But as the country invested more in research and conflict rocked Europe, foreign scientists increasingly migrated to the states. Most famously, this exodus included Albert Einstein, who escaped Nazi Germany, eventually landing in the U.S., and Enrico Fermi, who fled fascist Italy by attending the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm and from there decamping to New York City. At the time, most researchers emigrating to the U.S. hailed from Europe, some of whom, like Fermi, contributed to the Manhattan Project.

This trend helped fuel the United States as it rocketed to scientific preeminence. From 1941 to 1950, researchers working at U.S. institutions represented 47 percent of all Nobel laureates in science categories, 19 percent of whom were immigrants.

“That was a period when the U.S. jumpstarted the golden age of science and innovation,” says Ina Ganguli, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Growing numbers of scientists from Asia, including India and China, began arriving in the U.S. in the 1960s. This coincided with the end of immigration quotas affecting Asian countries and, a decade later, the opening of China’s economy. The U.S. share of Nobels peaked between 1991 and 2000. During this period, U.S. scientists composed 72 percent of all academic Nobel laureates—a quarter of those prizewinners were immigrants.

Seeking bountiful academic opportunities, researchers and students across the world have continued to flock to the U.S. After receiving their Ph.D.s, the majority of international STEM students settle down here and start their scientific careers, some carving their path toward a Nobel or other accolades over the course of decades. One study, looking at the career trajectories of young medalists from the International Math Olympiad, found that those who immigrated to the U.S. went on to have more productive careers than those moving to other countries. This higher productivity in the U.S. has likely owed to more abundant resources and opportunity, says Ganguli, one of the paper’s authors.

Beyond awards, immigrants have outsized impacts on innovation—in 2011, 76 percent of patents awarded to the country’s top patent-producing universities “had at least one foreign-born inventor” on the team, according to a report from the Partnership for a New American Economy.

But over the past two decades, the share of international students at U.S. universities and colleges have declined. This is likely related to the rising costs of attending school here, Witte says, which are particularly prohibitive for people arriving from low- or middle-income nations. The COVID-19 pandemic, along with strict immigration policies from the first Trump administration, have likely also played a role, Ganguli adds.

Now, the Trump administration’s increasingly restrictive policies may exacerbate the slowing trickle of global academic talent to the U.S. by attacking academia on multiple fronts. For one, significant federal funding cuts and freezes threaten research programs that have long attracted people from around the world. Just getting here is becoming increasingly difficult. The administration introduced travel bans and restrictions affecting nearly 19 countries this summer, is ramping up vetting of student visas, and recently attached a hefty $100,000 fee to H-1B visa applications. This latter policy change could wreak “catastrophic setbacks” to U.S. research, according to higher education groups who recently filed a lawsuit challenging the fee.

Potential impacts on the U.S.’s Nobel chances likely won’t be obvious at first, says Patrick Gaule, an economist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom who co-founded the Global Talent Fund, a non-profit that supports STEM students across the world. Over time, more young students could opt to attend universities in nations other than the U.S.—taking their award-winning smarts with them.

“It’s a very long gestation lag with the Nobels,” Gaule says, because it can take decades for one’s research to mature to the point that it’s recognized by these awards.

But an exodus of scientists already further into their careers could yield more immediate effects, Ganguli says. Even in the early days of the current Trump term, Canada and Europe were courting U.S. scientists. Seventy-five percent of U.S. scientists polled by the journal Nature said they were contemplating leaving the country, according to a survey published in March.

“If we go at this rate with more [immigration] restrictions, then I think we will definitely see a long-run decline in U.S. science overall—measured by Nobel laureates,” Ganguli says. “The big question is, how soon is that gonna come?” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter

Lead image: AntonSAN / Shutterstock