It took nearly a century of research and advocacy for people with a rare and painful blood condition to receive effective treatment—and barriers still exist for these patients.

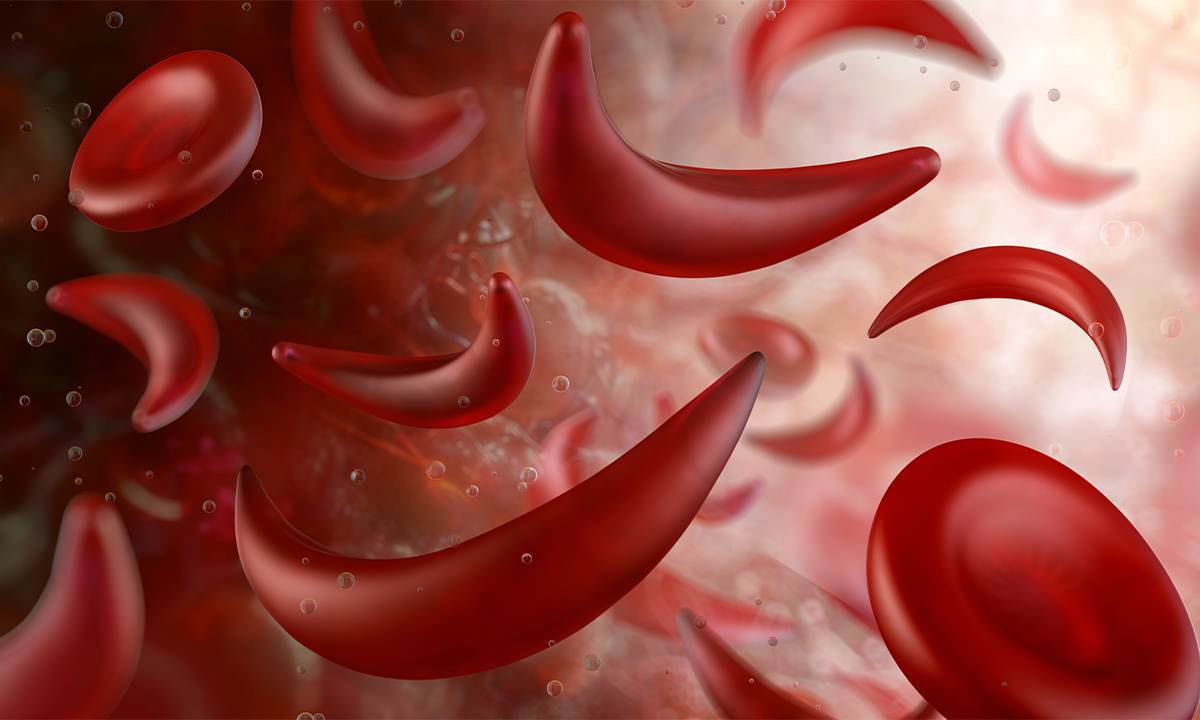

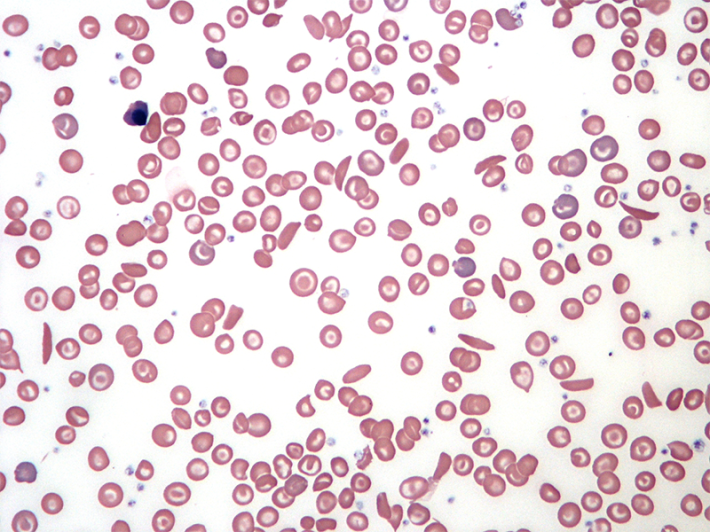

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited disease where one’s red blood cells are sickle- or C-shaped. They become rigid and sticky, which can slow or stop blood flow and impair the delivery of oxygen throughout the body. It’s one type of sickle cell disease, a group of inherited blood conditions.

Sickle cell anemia can trigger intense bouts of pain called pain crises and severe complications including stroke, organ damage, and vision problems. Sickle cell disease as a whole affects more than 100,000 people in the United States and 8 million people around the world. In the U.S., more than 90 percent of people diagnosed with these conditions are Black, and between around 3 and 9 percent are Hispanic or Latino.

Researchers suspected sickle cell anemia as early as the mid-19th century, when African scientists began describing specific cases in medical literature. And in 1910, physician James Herrick penned the first description of the condition in Western medical literature, documenting the case of Walter Clement Noel, a young dental student from Grenada.

A major breakthrough arrived three decades later: In 1949, researchers linked the disease to an abnormality in the structure of hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen in blood. This marked the first time scientists tied a disease to a shift in protein structure. A few years later, protein chemist Vernon Ingram pinpointed the specific genetic mutation associated with sickle cell anemia.

Even after scientists learned of the exact cause of the condition, research and medical care lagged for decades due to systemic racism. Beginning in the early stages of research, U.S. scientists perpetuated the myth that the disease only occurs among Black people. Some doctors claimed sickle cell disease proved that white people were biologically superior—misinformation that was eventually wielded to justify racial segregation.

In a 1969 survey conducted in Virginia, only 30 percent of Black respondents had heard of sickle cell anemia, and only 20 percent knew it was a blood disorder. Around that time, 12 states had passed laws that targeted Black people with mandatory sickle cell genetic testing.

Read more: “The Misguided History of Racial Medicine”

Advocacy by the Black Panther Party, which offered free sickle cell testing and education, pressured Congress to pass the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act of 1972. It gave the federal government the power to set up education, screening, and research programs.

Research progressed over the next decade, and scientists announced the first documented cure of sickle cell anemia. In 1984, scientists reported that an 8-year-old-girl who received a bone marrow transplant recovered from the disease—it was originally intended to treat her acute myeloblastic leukemia. This type of transplant became one of the few cures for sickle cell anemia.

Another major treatment milestone arrived this week in 1995, when doctors shared that they had found the first effective medication for the disease. Due to “promising results,” researchers ended a national trial early. The drug, hydroxyurea, was developed as a cancer treatment, but it was shown to attack “the underlying cause of the disease rather than simply combating its painful symptoms.” In 1998, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia.

More recently, scientists have made major strides with gene therapies for sickle cell disease. The FDA approved two such treatments in 2023, one of which was the first therapy ever approved in the U.S. to use CRISPR gene-editing technology.

While people with sickle cell anemia have far more options than they did a few decades ago, patients still face disparities in care and a lack of research funding compared with other rare diseases. It’s difficult for people with this condition to receive drugs for pain relief due to stigma from healthcare providers, for example, and relatively few doctors have experience treating it.

Despite recent cutting-edge treatments, the medical field has a ways to go to empower these patients. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Corona Borealis Studio / Shutterstock