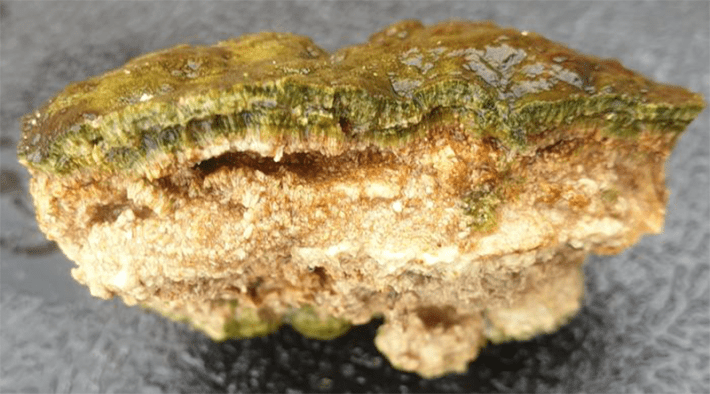

You might think you’re looking at a bunch of mossy rocks, but you’re actually gazing at some of the world’s oldest living creatures—and they’re doing great.

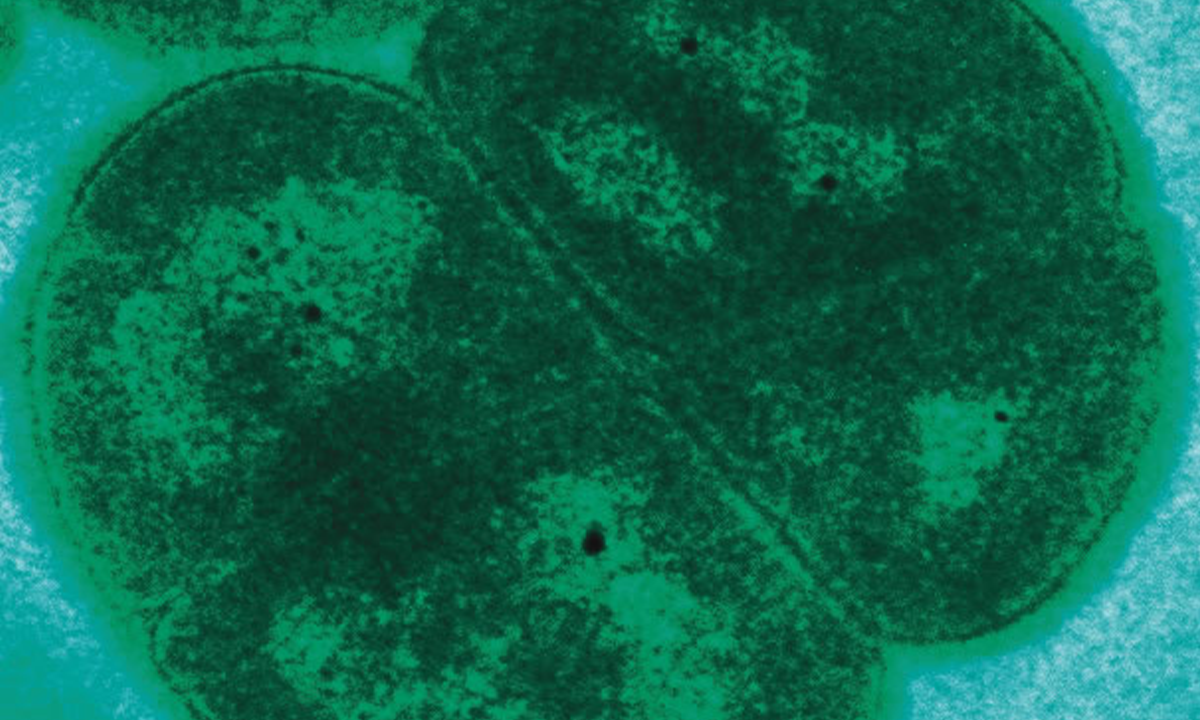

Communities of microbes gobble up dissolved minerals in water and turn them into these solid, rock-like structures called microbialites. Researchers have found fossilized microbialites that are around 3.7 to 3.5 billion years old, which might represent the oldest organisms found on Earth.

Around a billion years after that, microbialites may have transformed our planet forever—researchers think that photosynthesizing cyanobacteria building these structures injected oxygen into Earth’s atmosphere and oceans for the first time. This unique ability enabled them to dominate the planet until more organisms adapted to oxygenated living. Today, microbialites dwell in aquatic environments around the globe, including the super salty Shark Bay in Australia and freshwater lakes in Canada.

Read more: “When Did Life on Earth Begin?”

Researchers want to better understand how microbialites transformed the world’s carbon cycle and geological evolution many millennia ago, but it’s hard to glean such insights from fossils. To see how these creatures interact with their environment today, an international team of scientists inspected microbalites along the southeastern coastline of South Africa. These sites, with water full of calcium seeping from coastal sand dunes, provide uniquely tough conditions for life.

This work revealed that microbialites are far more than living relics, the team reported in Nature Communications. They grow remarkably quickly even in inhospitable environments, the researchers found, sequestering plenty of carbon along the way—the microbialites they studied take up the equivalent of up to about 3 pounds of carbon dioxide per square foot each year. Picture a tennis court-sized area locking away as much carbon dioxide as three acres of forest annually.

“These ancient formations that the textbooks say are nearly extinct are alive and, in some cases, thriving in places you would not expect organisms to survive,” said study co-author Rachel Sipler, a marine biogeochemist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine, in a statement. “Instead of finding ancient, slow growing fossils, we’ve found that these structures are made up of robust microbial communities capable of growing quickly under challenging conditions.”

Sipler and her colleagues were also surprised to learn that the microbialites sucked up roughly as much carbon during the night as during the day, which revealed that “the microbes are utilizing metabolic processes other than photosynthesis to absorb carbon in the absence of light, similar to how microbes living in deep-sea vents survive.”

Now, these mysterious living rocks offer compelling clues into both the Earth’s evolution and the future of carbon sequestration in a warming world. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Rachel Sipler, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences