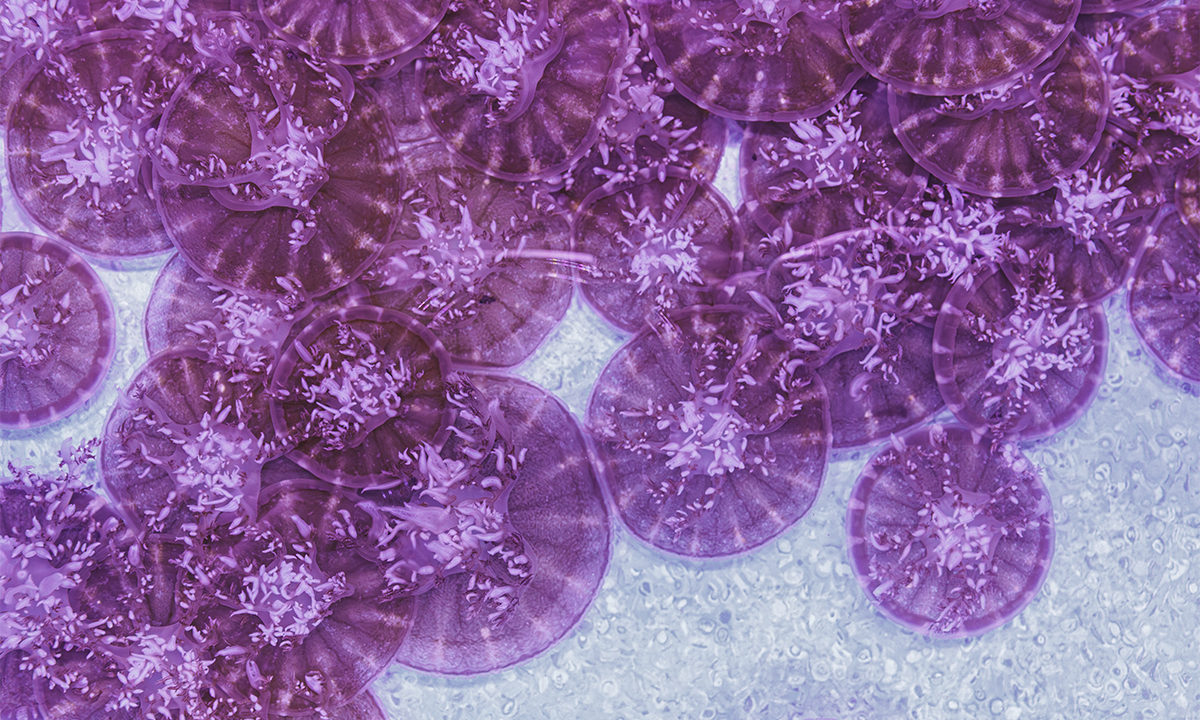

An old debate centers around what makes species vulnerable to extinction. Traditionally, the evolutionary age of a species was considered independent of how long it had been on Earth. Recently, evidence that age of a species affects its extinction risk has challenged this Law of Constant Extinction. In particular, in a new study, researchers at the University of Zurich (UZH) refuted the Law of Constant Extinction for sharks and rays.

The researchers reconstructed the diversification of neoselachians (the group that includes modern sharks and rays) by modeling data from 20,000 fossils dating to the past 145 million years. “We were particularly interested in identifying when, over the past 145 million years, large numbers of new species emerged or disappeared, and how this can be explained,” said first author Kristína Kocáková of UZH’s Department of Paleontology in a statement.

The model turned up six periods of high shark and ray extinctions, of which four were previously unknown, including the longest-lasting one at the end of the Eocene 33.9 million years ago. The findings highlight the vulnerability of the neoselachians over evolutionary time, with lots of speciation and species turnover.

Read more: “The Shark Whisperer”

The models also showed that extinctions were age-dependent, no matter the intensity of the extinction period. Newer species were more likely to go extinct than older ones, regardless of whether the extinction was caused by an asteroid or another factor. “If a species had existed for only about four million years, it was more vulnerable than one that had been around for 20 million years,” explained Kocáková.

Why would younger species be more likely to go extinct? The researchers suggested that younger species could be disadvantaged by smaller ranges and/or population sizes when extinction drivers strike. With an apparent selective pressure against young species of sharks and rays throughout deep time, age emerged as a persistent predictor of extinction risk.

Over their long history of ups and downs punctuated by multiple intense extinction events, neoselachians have been on a downward trend. The number of new species hasn’t made up for the species losses over the past 40 to 50 million years, according to the study findings.

“Modern sharks and rays have already lost much of their evolutionary potential and have now also come under pressure from humans,” concluded coauthor Dr. Daniele Silvestro from ETH Zurich. “Understanding their past helps us recognize how important it is to protect the species that still exist today.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Wonderful Nature / Shutterstock