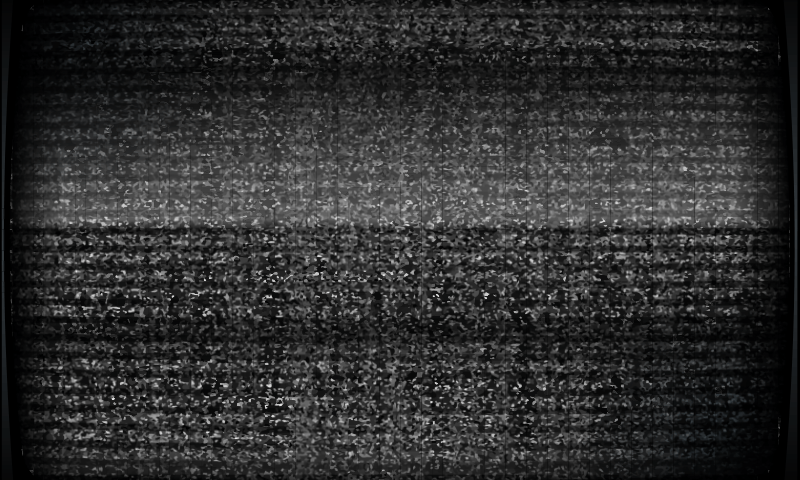

Flickering dots and smudges of light everywhere, fuzz and static blanketing my visual field, blurring the edges of my reality. For as long as I can remember, this is what I have seen when I look out onto the world. It is as though someone tuned a television inside my head to an unreachable channel, and it got stuck there, or I became permanently submerged in a child’s snow globe. But I didn’t realize this was unusual until I mentioned it to my partner in a dark hotel room in Scotland a few years ago.

I soon learned that I have a condition called visual snow, a rare neurological syndrome that affects 2 to 3 percent of the global population. Some medical professionals used to believe that it was psychosomatic. Others thought that the condition was caused by drug use, because the visual symptoms overlap with a disorder known as HPPD, a distortion of the perceptual system that can persist months to years after use of hallucinogens. But over the last decade, research has revealed that it is more likely a neurological condition than a psychological one, and that most people who have it never used psychedelic drugs—almost half of people with visual snow report experiencing it since early childhood. Some scientists believe it may be vastly under-reported and are still puzzling over the root cause.

Visual snow is the “noise” a healthy person’s visual system filters out.

In 2014, a set of diagnostic criteria were established for visual snow for the first time: The most central criteria is the snow itself: dynamic dots of light that flicker across the entire visual field for at least three months. But most sufferers also experience at least two of four other diagnostic criteria: persistence of after images (known as palinopsia), excessive floaters, impaired night vision, and sensitivity to or intolerance of bright light. In more severe cases, migraine and tinnitus are also common. Other cognitive disturbances can also arise, such as feelings of detachment from oneself, anxiety, depression, brain fog, insomnia, vertigo, and pins and needles in the extremities.

Neuroscientist Owen White, a professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, first took interest in visual snow in 2012, after a series of patients came to him with some of the strange visual symptoms now recognized as diagnostic criteria for the syndrome. No doctors would take them seriously, his patients told him. White says he has been studying visual snow since and now consults with the Visual Snow Initiative, a nonprofit dedicated to education, research, patient advocacy, and treatment development. White’s research suggests that the strange visual symptoms sufferers experience are, essentially, the “noise” that a healthy person’s visual system filters out.

“The brain is initially, from birth, bombarded by sensory stimuli and has to learn to filter all those stimuli—a little like noise filtering headphones—in order to produce a coherent signal,” says White. But with visual snow, something interrupts the feedback loops in the brain and retina, which interferes with the filtering process, he says.

How and when this malfunction in the visual processing system happens is still unclear. White and others say it may be present at birth, develop in early childhood, or occur after some form of brain dysfunction induced by disease, although there is no clear association with any specific pathology.

Neurologist Christoph Schankin, who also participates in the Visual Snow Initiative, agrees with White and others that the syndrome is caused by a failure of the visual system to filter out noise. He says it all begins with an overamplification of signals from the primary and secondary visual cortices of the brain, which have been shown to respond to the orientation of edges, lines, and objects, as well as color, spatial frequency, and patterns. Schankin has also published research showing that visual snow can be accompanied by not just tinnitus and migraines, but also fibromyalgia, a condition that features musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep, memory, and mood issues. All four conditions—visual snow, tinnitus, migraines, and fibromyalgia—are marked by hypersensitivity to stimuli.

Scientists like White and Schankin are still trying to understand not only what causes visual snow syndrome, but also how to treat the condition, particularly for the most severe cases. For some, it gets worse over time: They may start with visual symptoms alone, but later develop migraine and tinnitus and other cognitive symptoms. Certain drugs have been found to help, including magnesium, cinnarizine, and flunarizine, but no treatments or lifestyle changes so far completely eliminate the visual or cognitive disturbances.

For me, visual snow is more of a nuisance than a debilitating disease, at least for now. But I am an artist, so my eyes are my instrument. They get easily tired, especially when I’m looking at a computer screen or at lights, and my everyday reality often seems out of tune—the reception is bad, the picture unclear. It’s worst when night comes. In the darkness, the static is most vivid. But eventually, the scattered stars dancing behind my eyelids drift away, and I sink into the dark abyss of sleep. ![]()

Lead image: Pro_Vector / Shutterstock