Not long ago, Alexander Langlands started whittling sticks. The archaeologist felt a subliminal longing toward the pastime. “It’s addictive,” he writes in his 2017 book Cræft: An Inquiry Into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts. “And evidently in my blood.”

When Langlands was growing up, he couldn’t remember a time when his father wasn’t carving intricate figures into walking sticks. But Langlands never guessed he’d find himself in his father’s place, relishing the pastime himself.

Langlands has a fascinating theory about stick-making—that is, shaping logs or branches into tools or weapons. “Sticks are probably where the story of craft begins—the point at which our very distant ancestors progressed from animalistic existences to lives materially enhanced by the objects around them,” he writes.

The original carver paid close attention to the branch’s hard-to-work knots.

With his newfound fondness for the art of whittling, passed down from his dad, Langlands began to wonder if stick-making wasn’t passed down from our earliest ancestors. In fact, he wondered if, for early man, stick-making weren’t just as “sophisticated” as stone tool making, meaning systematically designed and requiring substantial skill to produce.

It's “almost inconceivable that Australopithecus, Homo habilis, erectus, neanderthalensis, and sapiens did not develop this technology to the same degree of sophistication as they had stone-tool technology,” Langlands writes. “But because of wood’s inability to survive in the archaeological record, it will forever be a story that remains untold and one merely hypothesized by the daydreaming of experimental archaeologists such as myself.”

But now the story is being told. True, wood decomposes (thank you, fungi). But exceptions exist and researchers are beginning to study them closely. The Schöningen spears, excavated in Germany in the 1990s, are 300,000 years old, predating modern humans. The weapons—which include a couple of finely crafted smaller double-pointed “throwing sticks”—exhibit “outstanding preservation,” according to Nature, after being buried and escaping any exposure to oxygen for so long.

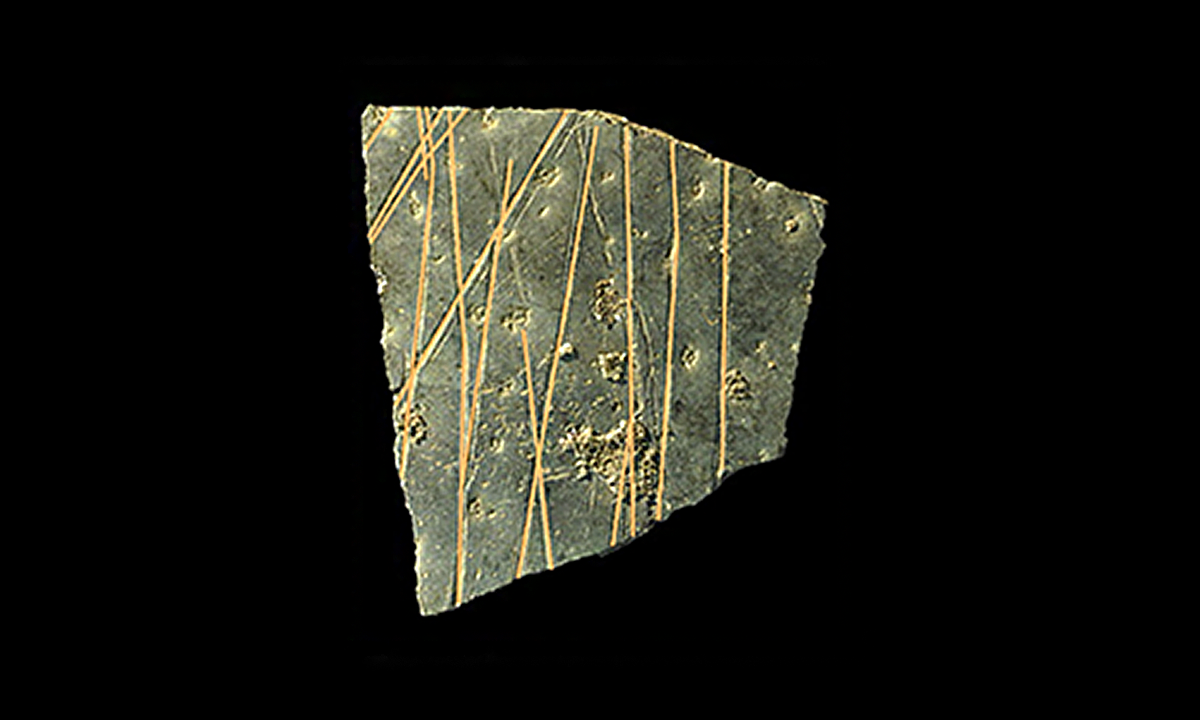

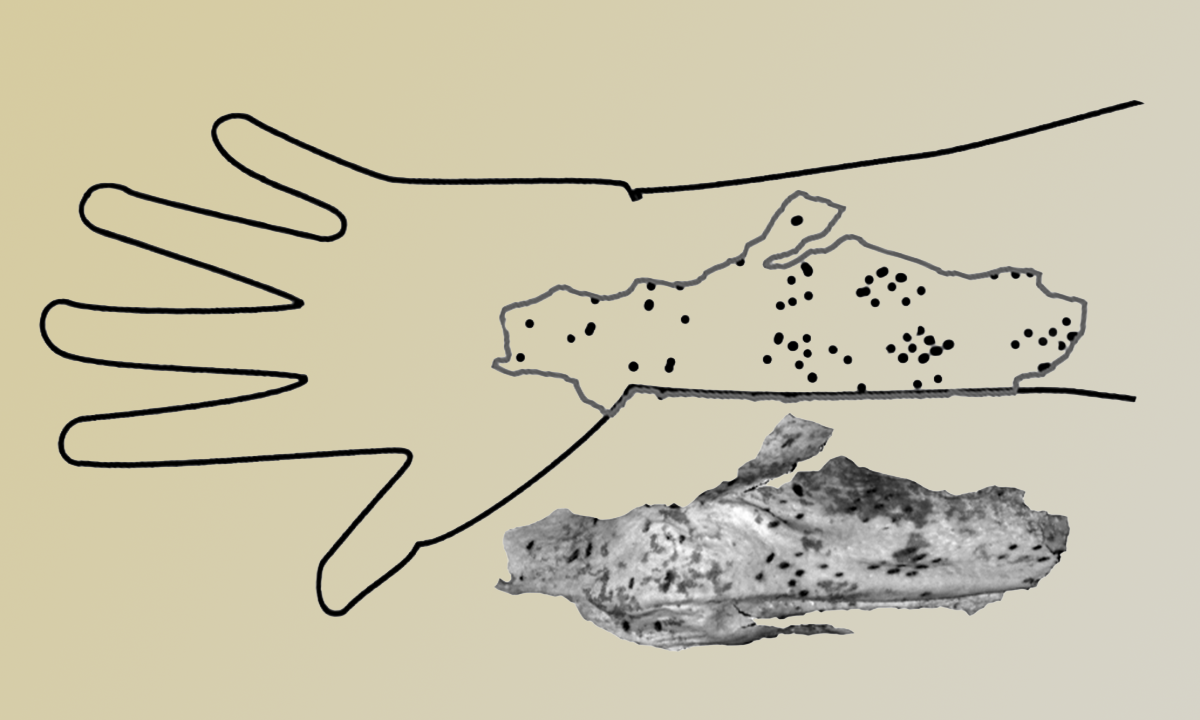

One of the Schöningen throwing sticks is the star of a new study led by Annemieke Milks, an archaeologist at the University of Reading. She and her colleagues put the stick, carved from a spruce tree branch, under the proverbial and literal microscope. To create a 3-D model of the stick, Milks and colleagues also used a microcomputed tomography, or microCT, scanner. Then they chemically analyzed the wood, examined its tree rings, and noted various microcuts and spots where the wood showed more compression. This helped the researchers establish the throwing stick’s “cultural biography”—where it was sourced; how it was manufactured, used, and maintained; and how it was discarded.

The original stick carver paid close attention to the branch’s hard-to-work knots, shaping “all but two of them down to be flush with the surface,” Milks and her colleagues write. “The aim of this was likely to improve handling for ergonomic purposes, and to improve aerodynamics by reducing drag. An absence of significant surface or internal drying cracks suggests the wood dried slowly and evenly. Cut wood loses its natural moisture until it is in equilibrium with the surrounding environment, and if freshly cut and debarked wood is allowed to dry too quickly it can develop significant cracks and can also warp.”

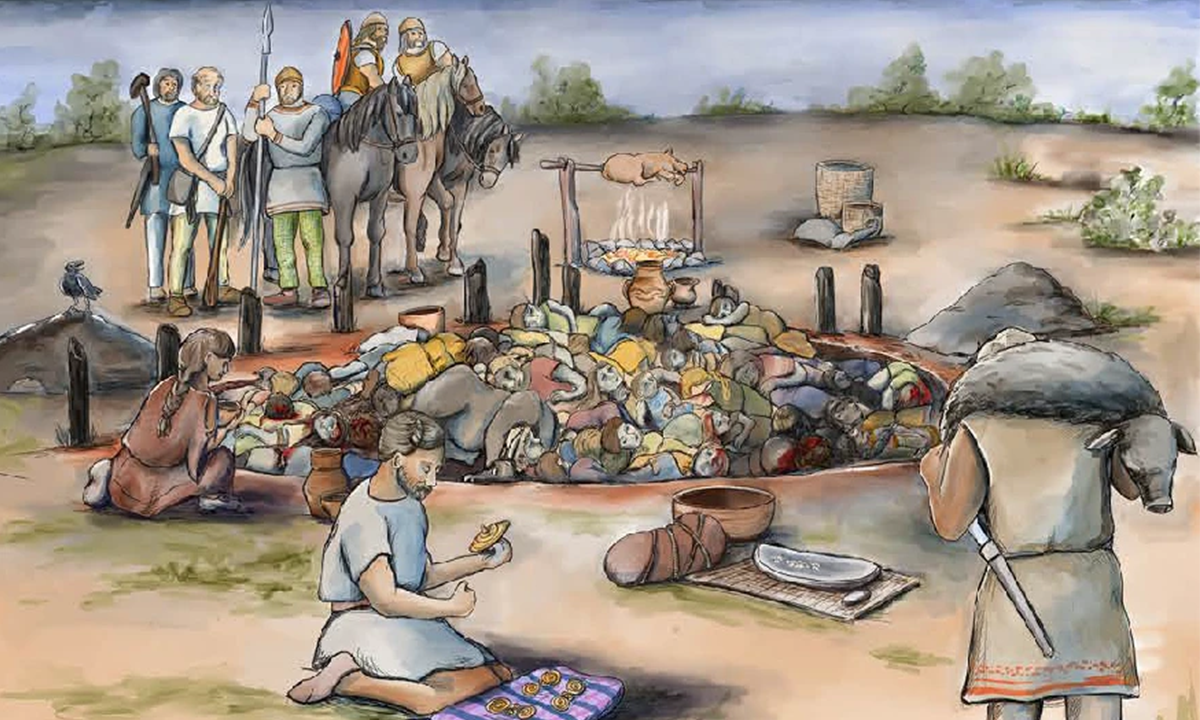

The Schöningen spears show that stick-making was a highly advanced technology. The throwing sticks are light, good for hunting rabbit-sized prey, and are potentially easier to use than larger wooden spears. “The Schöningen hominins,” Milks and colleagues write, “had the capacity for remarkable planning depth, knowledge of raw materials, and considerable woodworking skill, resulting in an expertly designed tool.”

Currently the throwing sticks are on display at Forschungsmuseum, in Bonn, next to the Schöningen excavation site. Museum scholars echo the researchers’ conclusions, writing the weapons significantly inform what we know about Homo heidelbergensis, the early human species that lived about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago. “Planning, communication, technological skills, sophisticated hunting strategies, and a complex social structure were among his abilities,” the museum informs us.

Langlands may have to revive his theory about stick-making technology. The Schöningen sticks suggest our ancestors’ tool-making prowess is not only carved into stone but whittled into wood. ![]()

Lead image: daseugen / Shutterstock