Biological anthropologist April Nowell had been studying the skeletons of Ice Age children for two decades when she began to see her own kids in a new light. They had just hit puberty and her house was suddenly filled with gangly teenagers, who ate voraciously and had to be dragged out of bed most mornings. It made her want to know more about the fascinating changes we undergo between childhood and adulthood—only in her study subjects, most of whom lived thousands or even millions of years ago.

So Nowell conducted one of the first studies of puberty in a population from the Paleolithic period. Often referred to as the Ice Age, the Paleolithic period took place during the early phase of the Stone Age, when humans made tools and weapons of stone. Nowell analyzed the teeth and bones of 13 Paleolithic individuals who died in adolescence around 25,000 years ago, and estimated that for the majority, puberty had begun by 13.5 years of age—only slightly later than most humans today. There was some variability, however, with a few individuals taking several years longer than their peers. Nowell and her colleagues also examined details of the children’s burials and trace DNA. The research was published in the Journal of Human Evolution last week.

The findings surprised her, Nowell says. “There's this sense in pop culture that adolescents today are entering puberty far earlier than ever,” she says—some people blame the hormones in milk or environmental chemicals for the perceived change. “But much to our surprise, we saw that adolescents today are actually following a blueprint for puberty that was set thousands of years ago.”

The researchers relied on methods used to analyze skeletons from medieval and certain prehistoric populations. Studying the mineralization of a person’s canine teeth, as well as the maturation of the bones of the hand, elbow, wrist, neck, and pelvis, can reveal what stage of puberty an individual had reached at their time of death.

There's this sense in pop culture that adolescents today are entering puberty far earlier than ever.

Overall, Nowell says the skeletons were healthy, with the obvious exception that these individuals died during adolescence—though their bones did exhibit some pathologies, including trauma in at least five of the 11 individuals, suggesting they led a physically demanding and hazardous lifestyle. They also had muscular right arms—suggesting that they were participating in the group’s hunting and gathering activities. “They were likely taking active roles in the kinds of things that promote the security and well-being of their communities,” she says, “and making important contributions to the overall survival of their communities.”

The data collected also suggests the Paleolithic kids underwent growth spurts similar to those experienced by modern humans, but significantly shorter than those of medieval children—in other words, they matured faster, which the researchers took to suggest that the Paleolithic kids lived in a healthier environment. The timing of puberty has long been recognized by biologists and scholars as a sensitive barometer of the kinds of environmental conditions that might contribute to healthy growth—as well as an important reflection of longer-term trends in human evolution, says Sharon DeWitte, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who was not involved in the new study. But puberty dating as a tool of inquiry has only recently come to the attention of bioarchaeological researchers.

“This paper provides much-needed information about pubertal timing in the distant past,” DeWitte says. “The finding that the timing of certain stages has not changed provides further evidence of how tightly constrained this part of the life course is, from an evolutionary perspective.”

Nowell hopes to learn more about how teenager-dom was understood in the culture at the time—was it considered a special and rarefied life stage? She also hopes to study Neanderthal bones, because the timing of Neanderthal maturity is in debate amongst bio-anthropologists. She wants to tell what she calls osteobiographies—the stories written in the bones of people from the past.

Some hints may emerge from societies outside of the industrialized west. Ethnographic data from hunter-gatherer foraging societies show that teenagers tend to grow up in mixed-age and mixed-gender groups, and that by the time they hit adolescence, their roles are pretty clear. “They don't have to try and figure out where they fit into society,” Nowell says. “Their place in that community is well known, and so they don't go through that kind of teen angst that is the basis of every coming-of-age movie.”

Studying teens who lived thousands of years ago has given her a bit more empathy for the habits of the young adults in her own house. Nowell’s teens would stay up so late and sleep so late it would make her crazy, she says. But studying the evolution of groups with adolescents made her think of the ways that having someone up late and monitoring safety may have been an evolutionary advantage for small groups in the past.

Nowell would imagine a paleolithic teen in repose, lying by a crackling fire under a blanket of stars. Maybe there was a dog barking or a baby crying, but most people would be sound asleep, except for a solo teenager who's looking up at the sky and dreaming, she says. “I just love that idea, and it really helped to lower my temperature when it came to my own kids sleeping until two in the afternoon.” ![]()

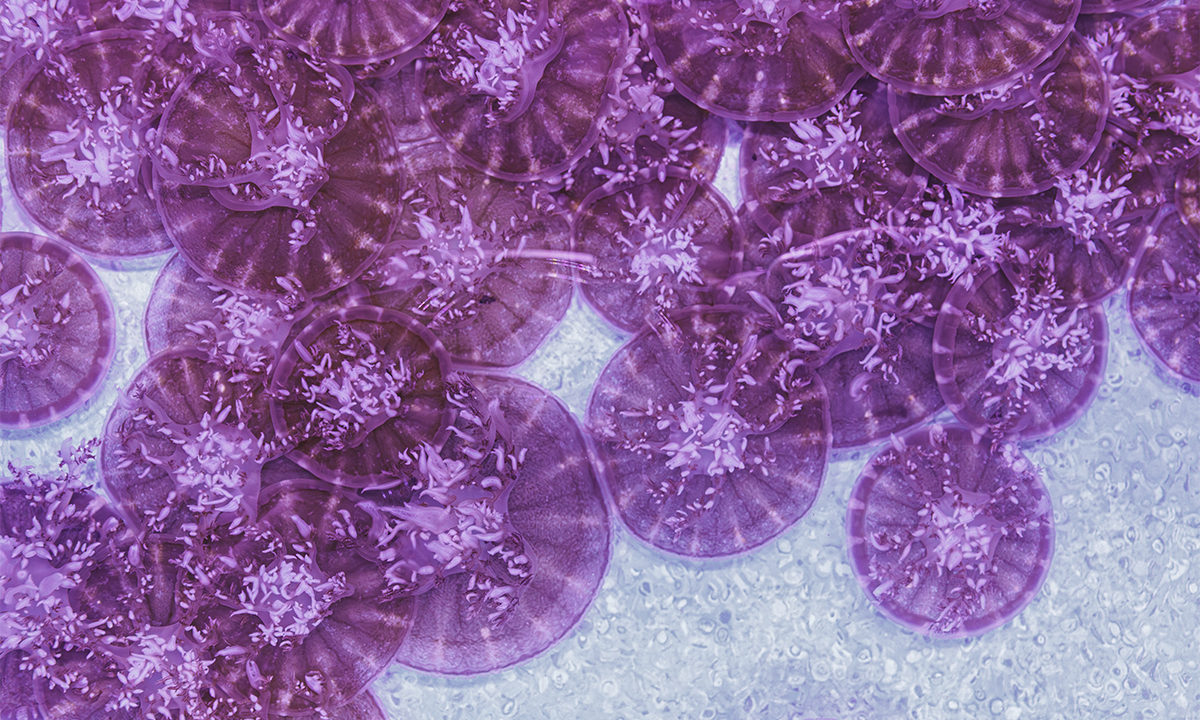

Lead image: Olga Kuevda / Shutterstock