Nearly a century ago, a young amateur astronomer from humble beginnings made his mark on cosmic history by discovering Pluto—though he didn’t live to learn of its shifting legacy.

Clyde Tombaugh, who was born on this day in 1906, grew up on a farm in Kansas and was captivated by sights of the moon and Saturn through his uncle’s small telescope. By the time he was 20, he started building his own.

He sent his sketches of Mars and Jupiter to Vesto Slipher, director of the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. Slipher enlisted Tombaugh with the mission of hunting down “Planet X,” a mysterious world thought to explain odd features of the orbits of Neptune and Uranus. This planet was predicted to have a similar mass to Neptune’s, orbiting the sun somewhere beyond that giant world.

The elusive planet was proposed by astronomer Percival Lowell, who had some out-of-this-world ideas. He initially claimed that a network of canals on Mars pointed to alien life, prompting him to build the Lowell Observatory. But after failing to prove this theory, he shifted his focus to Planet X. Lowell died in 1916, a year after Slipher became assistant director of the observatory. He stepped in as the director a decade later.

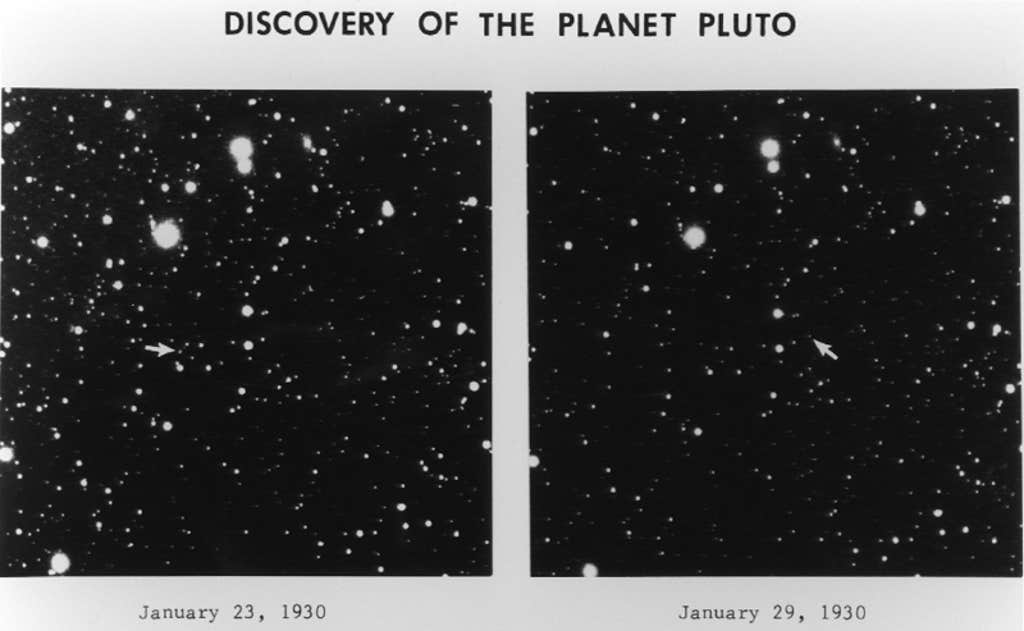

Tombaugh arrived at Lowell Observatory in 1929 and started off by capturing images of possible real estate for Planet X on glass photographic plates. In each spot of the sky, he took two photos a few days apart—a possible planet would travel within the frame in this period, enabling direct comparison. In February 1930, he noticed that an object shifted about 3 millimeters between two exposures. He estimated that this object’s orbit fell outside of Nepune’s, aligning with Lowell’s hypothesis.

The observatory proclaimed this finding to the public a month later. The newly unveiled world received the name Pluto, as suggested by 11-year-old Venetia Burney Phair from England. The moniker references the Roman god of the underworld, whose helmet gave him the power of invisibility.

Read more: “The Carouser and the Great Astronomer”

Around that time, some scientists had their doubts. Astronomer Ernest W. Brown called Tombaugh’s finding “purely accidental.” No telescope at the time could resolve Pluto as a disk, which was possible for all other planets. This hinted that Pluto was quite petite.

Pluto’s precise size wasn’t pinned down until 1978, when astronomer James Christy found its moon, which he named Charon. It turned out that Pluto’s mass is around two-tenths of a percent of Earth’s, far too tiny to warp Neptune’s orbit. In fact, Pluto is only about half as wide as the United States.

Pluto’s fall from grace arrived in 2006, when the International Astronomical Union adjusted its definition of a planet. The new meaning required an object to circle a star, for example, and to have knocked other debris out of its orbit—this specific factor stripped Pluto of its planet title.

Tombaugh never learned of this news, as he died in 1997, but after his Pluto revelation, he continued his career in astronomy. He went on to discover hundreds of stars and asteroids, along with two comets. Tombaugh also reported UFO sightings on multiple occasions.

In the same year that Pluto got demoted, NASA launched some of Tombaugh’s ashes into the stars aboard the New Horizons probe. This enabled Tombaugh to finally reach Pluto, in a sense, in 2015, when the probe became the first spacecraft to peer at Pluto up close.

The intimate encounter revealed intriguing details about the dwarf planet, like nitrogen glaciers and hints of volcanic activity that could help scientists better understand other distant, icy worlds. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: NASA