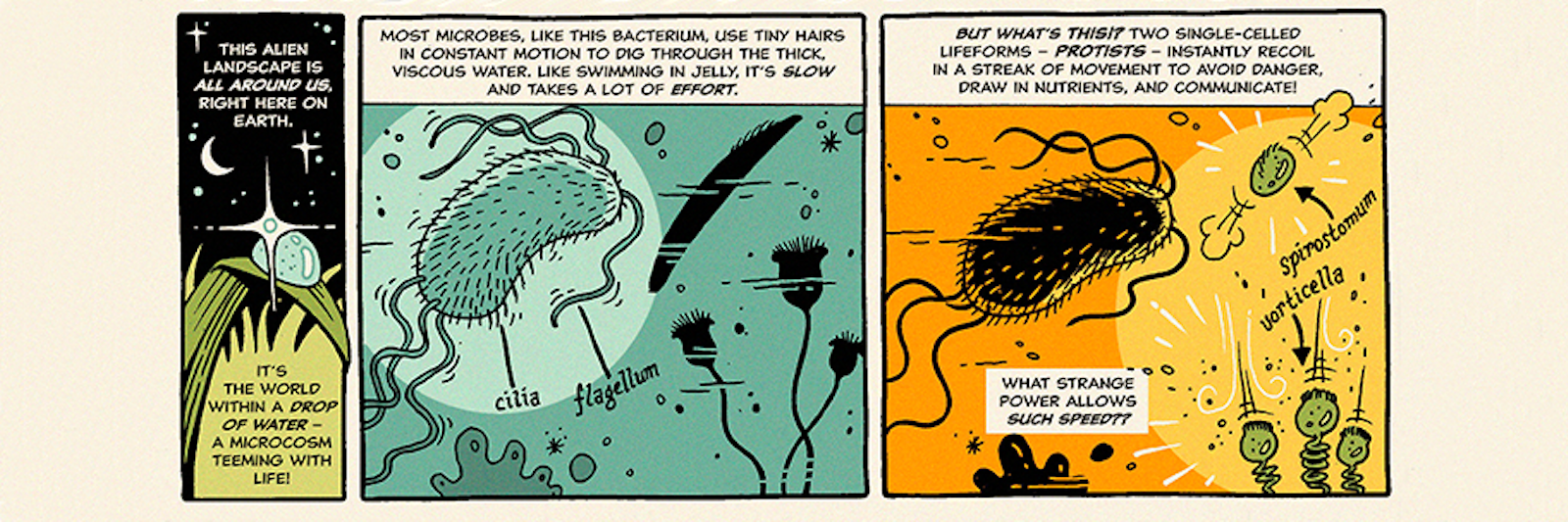

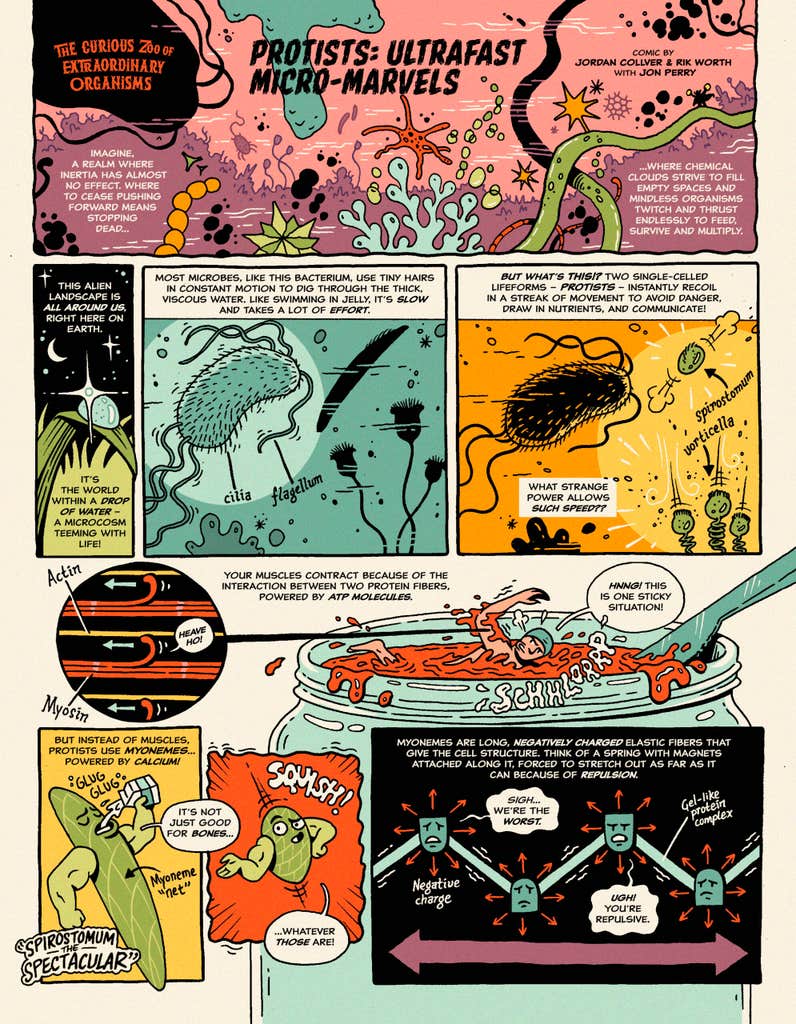

In any given drop of pond water, you may find a surprising spectacle: some of the tiniest creatures on Earth contorting and twisting at lightning speed, like miniature break dancers. These ciliated protists—single-celled organisms that get around and gather food with little protruding hairs like a 5-o’clock shadow on an unshaven chin—have evolved the ability to make some of the fastest motions known in the biological world. Ultrafast movements help them flee predators, communicate with their neighbors, and mix up their food.

Scientists have observed this behavior in a wide variety of protist species, but they don’t really understand how they pull off their speedy stunts. That’s partly because the protists come in such a remarkable variety of shapes and sizes: There is the wine-glass-shaped Vorticella, the cigar-shaped Spirostomum, the trumpet-shaped Stentor, the tear drop-shaped Lacrymaria, and the chandelier-shaped Zoothamnium. A simple mathematical model for the contractions across species could, among other things, help synthetic biologists build artificial cells that are able to mimic the protists’ ultrafast feats.

Recently, scientists in the Bhamla Lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology, together with colleagues from a number of other universities in the United States, set out to create such a model using experimental measurements in two species: the wine-glass-shaped Vorticella and the cigar-shaped Spirostomum. The comic below, created by artists Jordan Collver and Rik Worth, describes the lab’s findings, which were published in a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Jordan Collver is an illustrator and research communicator using visual narratives in comics to explore themes of science, nature, and belief. He is an associate lecturer in science communication at The University of the West of England and the artist for the Eisner-nominated comic Hocus Pocus: Magic, Mystery & The Mind. His work has been featured in The London Natural History Museum, The Journal of Science Communication, Slate, Physics World, Science for the People, Skeptical Inquirer, The Nib, and several comic anthologies. He sounds Canadian but lives in Bristol, UK. You can find him at @JordanCollver and https://jordancollver.myportfolio.com/

Rik Worth is a freelance comic book writer and journalist based in Leeds, England. When he isn’t writing about culture and class he writes comics about history. He has bylines in The Independent, Huffington Post UK, and Prospect Magazine.