Most of the universe’s heft, oddly enough, could come in the form of particles billions of times lighter than the electron—a featherweight itself, as particles go. Streaming through the cosmos in thick hordes, these wispy “axion” particles could deliver a collective wallop as the missing dark matter that appears to outweigh all visible matter 6-to-1.

For decades, physicists have searched for the axion’s chief rival: a sluggish and far heavier dark matter candidate known as a WIMP (for “weakly interacting massive particle”). But WIMP experiments remain empty-handed as researchers approach the edges of their search field, while the hunt for the axion is only beginning.

“Dark matter could still be WIMPs, but every day it looks a little bit less likely,” said Ben Safdi, a physicist at the University of Michigan who specializes in dark matter. The axion “is kind of the best dark matter candidate that we have at the moment,” he said, given that others have failed to turn up in experiments.

The Axion Dark Matter Experiment (ADMX) at the University of Washington in 2018 became the first experiment sensitive enough to detect the most likely kind of axion, and the experimental team recently announced the results of their latest search. They did not catch an axion. But, as they reported in a paper currently under review for publication in Physical Review Letters, they were able to rule out a swath of possible axion masses four times wider than the mass range they explored in their first run. ADMX is continuing to sweep through the places where an axion is most likely to be hiding. “They’re leading the charge,” Safdi said.

The axion attracts believers because it could solve two enigmas at once. Its invisible presence would explain why the universe acts so much heavier than it looks. And the particle would also show why the two fundamental forces that shape atomic nuclei follow different rulebooks—which is why physicists devised the axion in the first place, in the 1970s.

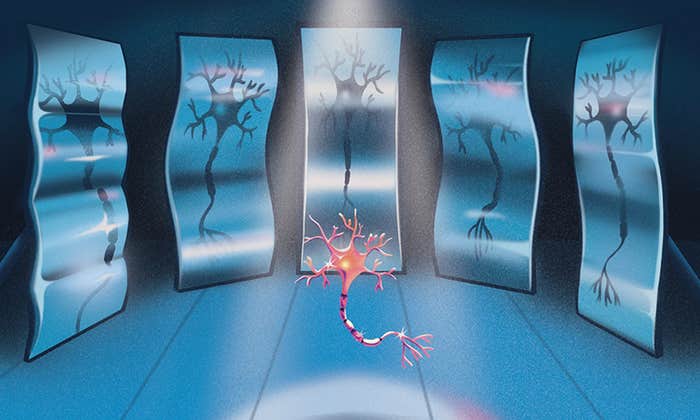

The axion would be something of a spiritual cousin to the photon, but with just a hint of mass.

The puzzle is that the strong nuclear force arranges particles inside the neutron, known as quarks, so that their overall charge seemingly never grows lopsided. This property showcases a peculiar equanimity on the neutron’s part called charge-parity (CP) symmetry: Inverting each quark’s charge and reflecting them all in a mirror doesn’t affect the neutron’s behavior. A neutron with lopsided charge would fail CP symmetry, because reflecting it would flip its electric field relative to its intrinsic angular momentum, an effect similar to looking in a mirror and seeing yourself wearing your sweater on your legs and your jeans on your torso. Real neutrons look the same in a mirror, as experiments have found them to be electrically uniform to at least one part in a billion.

This symmetry would be all well and good if physicists had not discovered in 1964 that the weak nuclear force doesn’t share it: Two-quark particles called neutral kaons decay in ways CP symmetry forbids. Since quarks are involved in both cases, experts would have expected the weak-force symmetry-breaking to extend to the strong force as well. Suddenly the neutron’s impeccable charge distribution became a puzzle—the “strong CP problem.”

The axion represents the leading solution, although the theorists who laid the groundwork for it didn’t immediately see the full picture. “I actually wrote down the equations just sort of fudging it to make it work,” said Helen Quinn, who proposed a way to restore balance to the strong force along with Roberto Peccei in 1977.

The strong CP problem boils down to the unexpected value of one constant—an angle labeled θ, or theta—in the equations that describe the strong force. Its value seems to be zero, which makes the neutron’s charges stay in line. But for the many other values θ could take, the quarks stray. After some fudging, Quinn and Peccei promoted θ from a constant to a field that permeates space, with a value that could naturally settle down to zero everywhere. Quinn compares her model to a tilted bowler hat: A ball can start at any angle around the rim, but it will always roll to the bottom. Two other theorists, Steven Weinberg and Frank Wilczek, soon observed that the Peccei-Quinn field requires a particle—an excitation in the field—and the axion was born.

Then, in the 1980s, observations of galaxies’ rotational speeds and other evidence increasingly suggested that a huge amount of the universe’s matter is invisible, interacting with everything else mainly through its gravity. The growing evidence for dark matter prompted Pierre Sikivie, a theoretical physicist now at the University of Florida, to calculate just how invisible the axion might be.

Sikivie explained in an interview that the axion would be something of a spiritual cousin to the photon, but with just a hint of mass. Since the photon—the particle of light and electromagnetism—is governed by Maxwell’s equations, Sikivie tweaked the classical theory to incorporate the axion and found that axions just might pack the universe tightly enough that they could add up to the missing dark matter.

He also calculated that axions wouldn’t be completely undetectable; now and then they would transform into two photons. He realized that saturating an area with a strong magnetic field (and thus lots of photons) would stimulate axion decay, just as photons ease the emission of other photons in lasers. Also like photons, axions are very wavelike, falling on the wavy end of the wave-particle duality. Their minuscule mass makes them extremely low-energy waves, with wavelengths somewhere between a building and a football field in length.

Sikivie realized that the key to coaxing these low-energy axions to turn into photons would be a device that could be tuned to resonate at precisely the same wavelength as the axions. He envisioned a machine called a haloscope that would amplify a signal, essentially ringing like a bell when an axion decayed.

Implementing Sikivie’s notions took more than 30 years, but ADMX is now sensitive enough to detect axions with masses that theorists deem most plausible, even if the particles decay at the lowest theoretical rates. With a potent magnet sitting in an icebox chilled nearly to absolute zero, ADMX slowly adjusts its resonance and scans for axions. How often the magnet might turn an axion into two photons is unknown, but with quadrillions of axions potentially passing through the experiment each second, a detection would become clear quickly.

In its first run, reported in 2018, the experiment scanned from 0.65 to nearly 0.68 gigahertz looking for excess power from axion-spawned photons; this year the collaboration has continued on to 0.8 gigahertz. These frequencies mean that the experiment has ruled out axions weighing between 187 billion times and 151 billion times less than the electron, with wider ranges to come. “We’re starting to take larger and larger chunks,” said Gianpaolo Carosi, a member of the collaboration.

The group expects to reach at least 2 gigahertz over the next few years and hopes to eventually push all the way to 10 gigahertz, which would correspond to an axion 12 billion times lighter than the electron. Estimates vary, but most theorists say an axion that does double duty as both dark matter and a neutron fixer should fall somewhere within that range.

If it hears nothing but static, ADMX won’t flat out disprove the existence of axions. Frequencies of a few gigahertz match the simplest dark matter schemes, but some theorists have cooked up more intricate recipes. And if dark matter is a mix of axions and something else, axions could span a mass range exceeding 10 orders of magnitude.

But as other promising dark matter candidates fail to materialize, more experimental groups are turning to axions. Some are developing terrestrial magnetic devices like ADMX, while others plan to scan the radio waves coming from nature’s mightiest magnets—neutron stars. Together these teams may someday cover most of the possible frequencies.

A discovery would permanently rewrite the laws of particle physics and cosmology, but today axions remain entirely hypothetical. Quinn just feels humbled that her musings have launched such a formidable search party. “Roberto and I spent a few months cooking up this theory,” she said, “and now the experimentalists have spent 40 years looking for it.”