“Take a pic of your feet on the carpet,” texted my sister. I had just landed in Portland, Oregon, to visit my siblings, and was walking to the airport exit. Autocorrect must have made a mistake, I thought. Yet I was a little curious. I glanced at the turquoise-blue low pile beneath my feet: dated and tawdry. Basically forgettable. But then she texted an explanation of sorts: “[There’s a] cult following for our carpet that’s being torn up.”

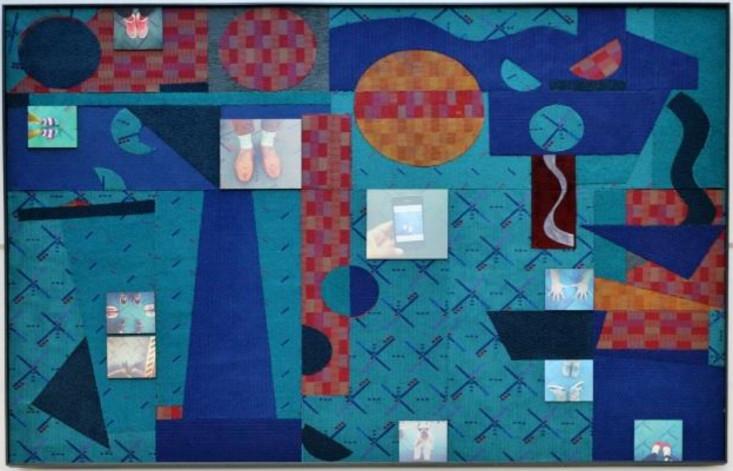

She wasn’t exaggerating. In the wake of an announcement that the 27-year-old carpet would be replaced starting January 23, 2015, people began to express a surprising connection to this humble, beat-up floor covering. There are carpet-inspired t-shirts, shoes and socks. Some enthusiasts are preordering tiles of it to install in their homes. Selfies with carpet are posted regularly using the hashtag #pdxcarpet (“PDX” being the three-letter code for Portland’s airport), and it has a Facebook page. Some people even had the broadloom’s abstract shapes—symbolizing a control tower and runways—tattooed on their bodies.

This is the #PDXCarpet to end all. let’;s see someone top this. Going to #Jamaica single coming back #married @FlyPDX pic.twitter.com/pHFF5GXejS

— Tip Vongbouthdy (@tippydoowhop) December 1, 2014

The carpet will not be fully replaced until November, and people are already intensely sentimental, which seems strange, because we usually think of nostalgia as backward-looking and connecting us to something significant. Some might even say this reaction represents something false, or culturally amiss. An op-ed in The New York Times eloquently discusses the downside to nostalgia for the present: “The nostalgia cycles have become so short that we even try to inject the present moment with sentimentality…nostalgia needs time. One cannot accelerate meaningful remembrance.” The writer also criticizes ironic attachment, which she said might be “good for a chuckle in the moment, but worth little in the long term.” Feeling maudlin over a tacky rug seems to be a great case in point. Why would people feel nostalgia for something that’s still here and seemingly trivial?

Until recently, most experts wouldn’t have had much good to say. For centuries, nostalgia was associated with negative feelings. The word comes from the Greek “nostos” for homecoming and “algos” for pain or grief, and was used in the 17th and 18th centuries to characterize homesickness. By the 19th and early 20th century, psychologists applied it more generally to any longing for the past, and counted among its detrimental effects escape from the present and dread of the future. Experts agreed that a person with nostalgia was suffering and maladapted to reality.

That’s no longer the case. Over the past 15 years, a number of psychologists have overturned the centuries-old view. “Studies show that nostalgia is complex, and though it has melancholic notes, it’s generally a sunny emotion,” says Wing Yee Cheung, a psychologist at the University of Southampton. “People experiencing nostalgia are brought closer to people and feel life has more meaning,” she says. (See Veronique Greenwood’s explanation of how old video games can trigger nostalgia.)

One insight from recent studies is that nostalgia is a social emotion. It decreases our loneliness and makes us feel rooted in a community. If you feel isolated or bored, simply recollecting a fond memory will lift your mood, researchers found. Wistful memories often involve other people or shared experiences, and when we think of these, we are reminded that we have a place in the world.

Scientists also discovered something rather paradoxical: Being nostalgic makes us hopeful about the future. In one study, participants were asked to listen music and afterwards explain how they felt. Those who heard a nostalgic tune versus a regular one felt an increase in self-esteem, which made them more optimistic about what’s to come.

Nostalgia also makes people feel warm—literally. One investigation had participants think of something while their hand was in cold water. Those thinking nostalgic thoughts kept their hands immersed longer and reported less discomfort from the cold.

And researchers have seen that, as with #pdxcarpet, people can sometimes feel nostalgia for something that’s not in yet in the past. “It’s called ‘anticipatory nostalgia’ because it [the object of nostalgia] is not gone yet,” says Cheung, “but they know they will miss it.” She likens anticipatory nostalgia to the sentimental longing parents feel when they reflect on their children leaving home, or to students on the brink of graduation. She says it often happens during times of transition. With respect to the carpet, she says that perhaps the trigger is “moving from the old classic carpet to the new one.” Cheung and a group of colleagues have preliminary plans to more rigorously study the phenomenon.

She also says that people can use anticipatory nostalgia to create happy memories, which they can draw on at a future time when they want to feel good. And the more surprising the memory, the more likely it will last. Perhaps this is where the triviality of the carpet is its very asset: memorializing something so banal is surprising. In this light, taking a selfie with the carpet is a joy-making machine.

It would be difficult to fully defend the culture of irony that is sometimes at play in the obsession with the carpet, or to argue that the carpet deserves aesthetic respect on par with great art that is appreciated non-ironically. But an understanding of psychology suggests we should appreciate how nostalgia for trivial or silly things can create meaning and connection in our lives.

For my flight home, I walked through the Portland terminal and surprised myself by feeling a little touched. Maybe it was emotional spillover from leaving my sisters. Maybe I missed my kids. Or maybe that turquoise-blue carpet was finally getting to me. Just in case, I took out my camera, pointed it at my feet, and snapped a picture.

Regan Penaluna is a senior editor at Guernica magazine.