You are at home, cutting onions for dinner, and tear up from the vapor. Your mother, teaching you how to cut onions when you were a child, pops into your mind: Guide the blade against the knuckles of your free hand, curling your fingertips inwards to protect them from the blade. Absorbed by the scene, you begin to think about how one day, if you have kids, you might pass that tip on to them.

Most people spend a considerable part of their waking lives daydreaming, their attention constantly fluttering from the task at hand to the thoughts, images, and memories moving through consciousness. Why is daydreaming so prevalent?

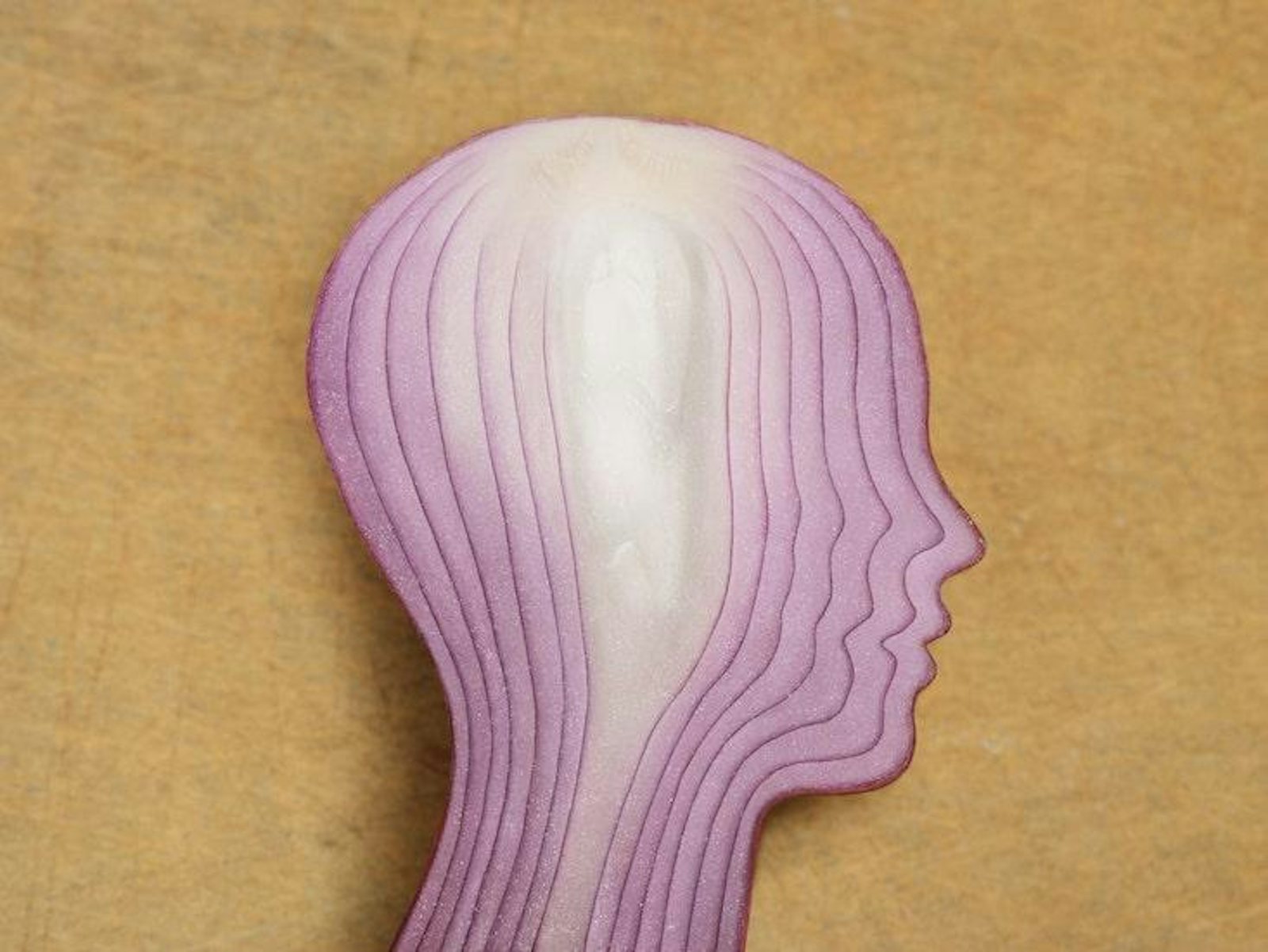

Having a story-like daydream may be more like looking at one’s reflection in rippling water than in a mirror.

The more I studied daydreams, the less clear their role seemed to be. I began with the observation that the majority of daydreams involve the self in one form or another. In our daydreams, fleeting or detailed, we are the main characters. We are self-centered beings—not in any pejorative sense—and the content of our daydreams reflects this. Self-related elements in consciousness—including beliefs, values, memories, and goals—are much easier to access than self-unrelated knowledge. In other words, information related to the self is more interesting or noticeable than most other things. So, what may make daydreaming important is that it provides a way for the brain to process self-related information to update our life story.

Storytelling is deeply ingrained in humans, whether it is through writing, music, visual art, or face-to-face conversation. People tell stories about themselves, to themselves, on a daily basis. These self-related stories allow people to make sense of who they are and to build their narrative identity—their sense of continuity through time. People need to connect who they believe they are to ongoing experiences.

As part of my doctoral research, I hypothesized that daydreams with a clear theme that flowed like a story and that linked elements of the story back to the self (to create meaning) would be beneficial for narrative processing. That is, I believed that the relatively spontaneous stories that take place within daydreams would help people update their concept of self with new and relevant information. I collected a large number of daydreams and coded them for story-like elements and for other important features: emotional intensity, specificity, presence of the self, presence of other people, timeframe (past, present, future, short-term, long-term), and realism (versus fantasy).

The results belied my hypothesis. Daydreams, I found, do not form perfectly crafted narratives like in a novel—or even like little stories you might tell a friend over dinner. Instead, daydreams seem to adopt certain elements of stories while also combining information in a fairly random fashion. They were most often structured in four ways, depending on whether they were highly emotional or highly realistic, and whether they related to a specific event or reflected broadly on a person’s goals, identity, and life.

Interestingly, only one category—daydreams that were realistic and specific—were related to the self-concept, and none of the categories helped people update their self-concept. This suggests that daydreaming may not include the conscious and thoughtful analysis that narrative processing needs. Having a story-like daydream may be more like looking at one’s reflection in rippling water than in a mirror. It disrupts the clarity of the self-concept by bringing new narratives into conscious awareness. But for these narratives to be integrated into clear and stable evaluations of self, a deeper analysis may need to occur, such as sharing personal narratives with another person or keeping a journal.

Certain daydreams reflect what is important to a person; what worries them, who they care about, and what they love and aspire to do. They’re made up of pieces of who we are. When these pieces reflect real life and flow like stories, we pay attention, we look, we become aware.

I recently daydreamed that I was standing in front of my new undergraduate students, introducing myself. The chalkboard was dusty, and the afternoon light shone through the window. My students were quiet for the most part, on their phones or computers. I felt slightly nervous and embarrassed that I couldn’t get everyone’s attention. Later, I realized that I was worried about making a good first impression. The subtle mix of these emotions in my daydream reinforced my identity as an instructor. I knew I was excited for the new school year to start.

Eve Blouin-Hudon is a psychologist and expert on creativity and imagination at Carleton University, in Ottawa. She also consults to organizations and individuals looking to learn about and master the creative process through her business, Bevy Creative, and co-owns a music and art collective that offers immersive experiences.