If you don’t know how something works, break it. Science is built on creative destruction: Much of what neuroscientists know of the brain, they know from what gets lost during brain injuries. Under happier circumstances, they glimpse the functioning of visual perception from how it breaks down in optical illusions. For instance, the 3-D Escher-like illusions created by Kokichi Sugihara of Meiji University exploit our brain’s tendency to see all angles as right angles.

Some of the most dramatic illusions involve apparent motion—these appear to spin, shimmer, or shimmy even though they’re completely static, like Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie–Woogie or the psychedelic pinwheels of Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a psychologist at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto. Two more Japanese mathematicians, Hitoshi Arai at the University of Tokyo and his wife, Shinobu Arai, have created a new class of them, known as fuyuu, or floating, illusions.

The Arais have an extensive online gallery with commentary in Japanese, as well as an abridged English version. In addition to their own creations, they have collected inadvertent illusions from the real world, such as buildings that, viewed from certain angles, appear to switch places because of how their windows and other design elements line up.

The Arais combine their art with theory: They try to reverse-engineer how our visual-processing neurons must work in order to account for these illusions. At fairly low levels of processing, individual neurons fire when they detect striped patterns, like little barcodes. Different neurons pick up patterns of different orientations, complexity, and positions. From these local responses, higher levels of the brain infer what you’re looking at.

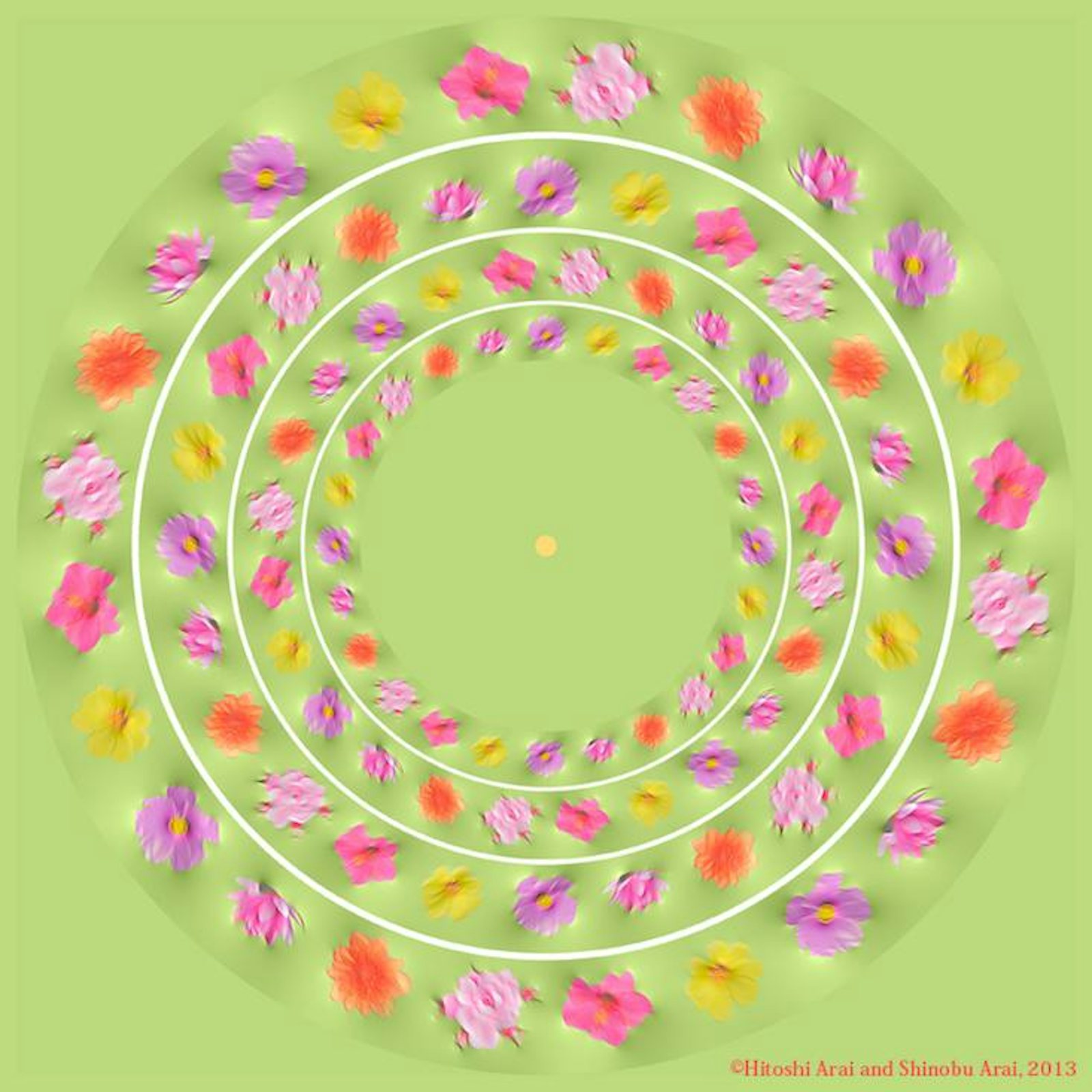

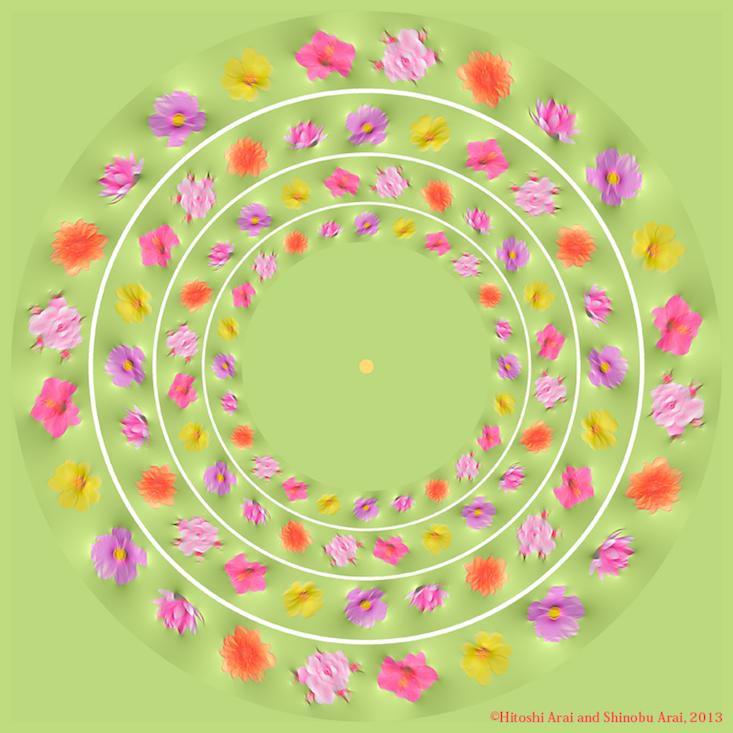

As a demonstration, the Arais created a variant of Fraser’s spiral illusion: a fractal pattern that you’d swear is a counterclockwise spiral, but is really a series of concentric circles (as you can verify by tracing your finger around the circumference). They suggest the illusion arises because part of our visual cortex, known as V4, contains neurons that respond to striped patterns that are tilted in just the way they are in spirals, and the illusory image contains these same patterns.

Using a mathematical technique called framelet analysis, the Arais seek to capture how the brain decomposes the image. To prove the technique does the job, they tinker with the image. When they filter out the spiral-evoking patterns, the illusion goes away, and you see the concentric circles for what they are. The filter is specific enough that its effect is barely discernible, except for de-illusioning the image. When they filter out only the components that evoke clockwise spirals, while leaving components that evoke counterclockwise spirals, the illusion looks even stronger than before—indicating that the misperception is the product of a competition between visual cues that pull in opposite directions.

The Arais do not merely dissect illusions, but can generate them, taking an image that looks boringly normal and making subtle changes, to color and contrast, to fool our brains. That gives them a systematic way to generate illusions rather than stumble on them by accident. What is more, they can apply the algorithm to any image, not just a geometric pattern. When they run a photograph of a natural scene through the algorithm, obscure details pop out. Hitoshi Arai showed me a mountain scene in Japan. After enhancement, the image reveals power lines and pylons that you can barely make out in the original. The technique amplifies the brain’s native ability to detect edges.

The Arais’ work demonstrates the central truth of illusions. They are not a deviation from reality. They are how we view reality. We see things by seeing things.

George Musser is a writer on physics and cosmology and the author of Spooky Action at a Distanceand The Complete Idiot’s Guide to String Theory. He is a contributing editor at Nautilus, and was previously a senior editor at Scientific American for 14 years. He has won the American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award, among others.