Henry Westphal is tired. It’s July 4, 1999, a Sunday. He and a friend are climbing the Mittelberg or “Central Hill,” a small mountain near Nebra, in central Germany. Both men know of ancient ruins located here. Equipped with two metal detectors, they hope to find something of value.

Westphal stops to rest for a couple of minutes. It’s a hot day and he’s out of shape. Suddenly his metal detector starts beeping wildly. He brushes some leaves aside with his shoe but can’t make out anything. The detector’s display reads, “OVERLOAD.”

With a pick, Westphal scrapes at the dry ground. Under a few inches of soil, the pick hits something hard several times. Together the two treasure-hunters dig a small pit. They find several objects: two decorative swords, two ax heads, a chisel, and two bracelets. The objects are piled beside a large, round disk oriented upright in the ground. Through the dirt sticking to the disk, a faint golden shimmer is visible.

The men take the objects, cover up the hole, and drive home. That night they go to a bar to celebrate the unusual and obviously valuable find. What neither of them knows is that the dirty disk would turn out to be a one-of-a-kind, 3,600-year-old artifact, later declared to be one of the most important finds of the 20th century.

After soaking the disk in a bathtub filled with water and dish soap for several days, Westphal sells it together with the other objects to an art dealer for 31,000 Deutsche marks (about 19,000 U.S. dollars at the time). The dealer knows the items are worth more and tries to sell them to several museums. The museums decline, realizing that trading in this ancient find is illegal. The disk ends up on the black market.

In May 2001, Harald Meller, the new state archaeologist in Saxony-Anhalt, hears about the disk. Photos show it’s in bad shape; Westphal had accidentally damaged it with his pick and inexpert cleaning. Meller, the State Criminal Investigation Office, and other officials come up with a plan to get the objects back. Like Indiana Jones, Meller knows that a find like this belongs in a museum.

The item of interest, now known as the Nebra Sky Disk, is a five-pound* plate of bronze inlaid with dozens of gold symbols. The gold figures include a lunar crescent, a large circle, and 30 small circles. After studying the disk for many years, archaeologists have concluded that it is the oldest concrete and accurate diagram of the sky ever found. The disk was a carefully made map used both for practical and religious purposes.

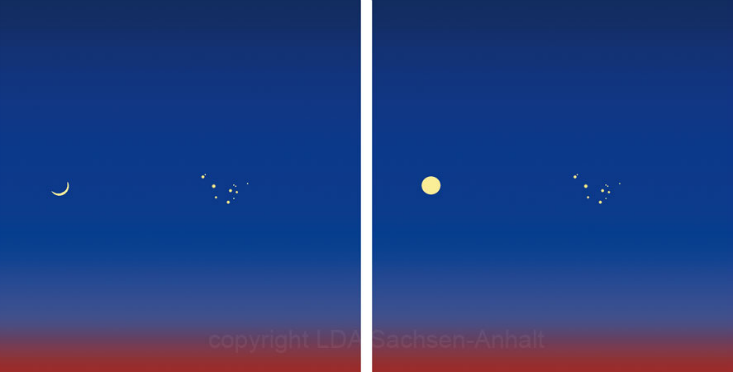

One of the most important components of the disk is a tight group of seven stars placed between the lunar crescent and the large circle denoting the full moon. They represent the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, a cluster of stars visible with the naked eye to people in the Northern Hemisphere. The Pleiades were known to, depicted by, and followed with interest by ancient cultures around the globe.

Researchers believe that the disk recorded the fact that when the Pleiades were seen next to a new moon, that signaled the beginning of spring, when seeds should be sown, at the latitude of central Germany. When the star cluster stood next to a full moon, it was a sign that fall had begun and it was harvest time.

Knowing about annual events such as the coming and going of the seasons was important for farmers whose lives depended on weather cycles. The Pleiades marked the time for the harvest and the plowing, as was mentioned in a poem by the Greek poet Hesiod, in about 700 years BC:

“When the stars of the Pleiades, daughters of Atlas, arise,

Then begin the harvest, but plough when they sink away (…)”

The disk had other astronomical functions, too. The trickiest job was synchronizing lunar and solar calendars. It takes about 29.5 days for the Moon to orbit Earth. That’s the time from one new moon to the next, and is the inspiration for our months. But 12 lunar months add up to a lunar year of 354 days, which is about 11 days short of the 365-days solar year. If you build your calendar around 12 lunar months, it quickly drifts out of sync with solar events like seasons.

For the people who built the Nebra Sky Disk, if the lunar and solar calendars got out of sync, then at the beginning of spring month, it wasn’t a new moon that appeared next to the Pleiades—it was a crescent moon.

“The winter solstice marked the birth of light.”

One way to re-sync the calendars is to add an extra month to the lunar calendar in some years; the Sky Disk illustrated just when to do that. When the Moon next to the Pleiades was as thick as the lunar crescent on the disk, they knew it was a leap year and they had to add a leap month, to get the calendar back on track. If they saw a new moon standing next to the Pleiades, they knew the calendars were in sync and they didn’t have to add a leap month.

Historians found that leap-year rule also mentioned in the Mul Apin, a Babylonian astronomical guide thought to have been compiled around 1,000 BC. In modern times, the lunar Hebrew calendar also adds an extra month to some years, while the Islamic calendar does not, so it is generally not in sync with the solar year.

The sophistication of the disk surprised many archaeologists. “We knew that people back then must have had a certain idea of the seasons and the Moon, as we all have,” said Dr. Alfred Reichenberger, a researcher and spokesperson for the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle. But scientists did not expect their knowledge to be so exact and deep. “There are depictions of the cosmos that are older, for example in the chamber tombs of the old pyramids in Egypt. But they are schematic…As of today, there has never been something as concrete as the Nebra Sky Disk.”

By studying the disk closely, archaeologists have found that it was not always in the same configuration it is now. After it was first built, sometime later in the Bronze Age, the disk found its way into the hands of new owners.Those new owners attached two golden arcs to the right and left edges of the disk to illustrate sunrise and sunset. (The left arc, representing sunset, is missing, but there’s a plainly visible mark from where it used to be.)

When the disk was held up on the Central Hill and aligned with the north as well as the horizon, the two upper ends of the arcs marked where the sun rose and set on the summer solstice, the longest day of the year. The lower ends of the arcs marked where the sun rose and set on the winter solstice, which plays an important part in many cultures. “The vegetation dies, the days become shorter—and then they start getting longer again,” says Reichenberger. “And in springtime, life awakens again so to speak. This component plays a part in many myths. The winter solstice certainly was a very important date for people in the north, because the days start getting longer again.”

“It marked the birth of light,” says Dietmar Luther, a tour guide at the visitor center in Nebra.

In February 2002*, Harald Meller, the state archaeologist, enters the foyer of the Hilton Hotel in Basel, Switzerland. He is there to meet a couple that acquired the disk and associated objects on the black market. By now the price has gone up to nearly a million Deutsche marks. Meller, posing as a potential buyer, sits down with the couple.

After talking for a while, the man pulls out the disk from under his shirt. It’s wrapped in a towel that he had taped to his stomach to smuggle it into Switzerland (an additional felony he would later be prosecuted for).

Meller pretends he has to use the bathroom and calls the police. Officers soon swarm the room and arrest the couple. Later Westphal and his accomplice are apprehended as well. Meller returns the objects to the state of Saxony-Anhalt. The disk is now on display at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle. Indiana Jones would be proud.

Since it was reclaimed, the disk has gone through careful restoration and extensive testing, and it continues to reveal more about its ancient creators. In October scientists found out that some of the gold on the disk originally came from Cornwall, in southwest England, showing that, at the time, there were long-distance trade relationships between what is now England and Germany.

Despite the careful workmanship and extensive planning that went into it, about 200 years after the disk was made, people decided to bury it. As to why, no one is really sure. Archaeologists have proof that at the time, the local society was going through dramatic changes. Old dynasties disappeared, funeral traditions changed. One theory is that people on the brink of a new era wanted to bury the sky disk as a symbol of the old world. Or it might have been buried as a sacrifice to the gods.

The disk would stay buried for around 3,600 years, until curious humans discovered it and use it as a window into the minds of people who lived so long before.

* Corrections: The piece originally said that the disk was nine pounds, and that it was recovered by authorities in February 2000.