This is part two of a three-part series about the movie industry’s switch to digital cameras and what is lost, and gained, in the process. Part one, on the traditional approach to filming movies and the birth of digital, ran yesterday; part three runs tomorrow.

Most people have an intuitive understanding that, for most of its history, digital video (DV) looked both less true-to-life and less beautiful than film. Early-generation DV was an extremely “lossy” format, delivering images that looked simultaneously harsh and muddy. Until very recently, the digital format offered an erratic and unnatural-looking color palette, especially when it came to human skin tones. Throughout their history, digital formats have typically had significantly less “latitude,” meaning the ability to overexpose or underexpose the image and still get a usable or pleasing result.

There are important technical differences between digital capture and film capture. Initially, the process is identical: Light is focused through a camera lens, one frame at a time. But in digital capture, there is no photographic emulsion and no chemical reaction. Instead, the light strikes an image sensor, a specialized circuit (most often the type called a complimentary metal-oxide-semiconductor, or CMOS) that converts light into electrical signals. Next comes the translation of that into digital data; images comprising an array of pixels. That happens later, entirely in the dark, by way of the proprietary codec (coder-decoder software) and formatting software found inside every digital camera.

While the director and cinematographer can manipulate the resulting data (meaning the output image) in any number of ways, they have no access to or control over how the data was encoded in the first place. With a digital camera, you’re always working within programming choices made by someone else. “These programs that decide how an image should appear were written by computer people, who don’t necessarily have a background in the visual arts,” says Gordon Arkenberg, who has shot several independent features, and teaches a course on the science of cinematography at New York University. This is what some cinematographers call the “black box” problem.

“I want to be able to have a ‘happy accident,’ where you pan the camera through the sun and have somebody walk through in a silhouette, and still have something on the side of their face in the silhouette. The reality is that there is no digital capture medium where you can do that right now.”

Photographic film, Arkenberg says, “was designed to fit quite naturally with how our visual system works.” In digital capture, he adds, the processes are made by people and often affected by a camera manufacturer’s desire to create a distinctive look. Arkenberg has conducted numerous tests with digital cameras. He says he has found that some digital cameras don’t render subtle highlight tones well, while others add an artificial sharpness to an image or intentionally desaturate the color, so that contrast and color must be manipulated to “look normal.” He believes the engineer who programmed a camera may understand colorimetry, the mathematics of color intensity, but does not possess an artist’s eye and cannot see “that this math does not always put color and tonality in the correct place.”

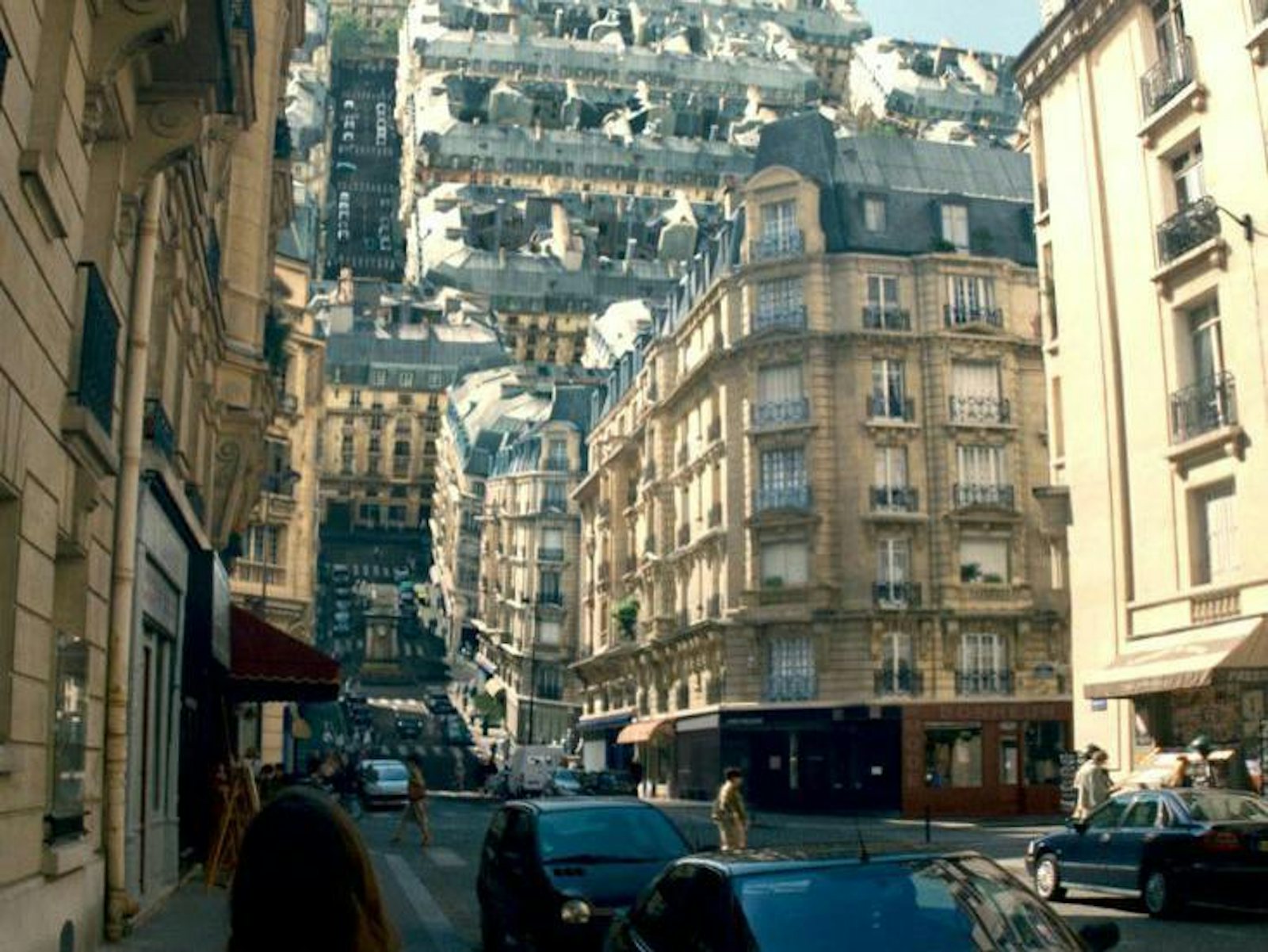

Wally Pfister—the Oscar-winning cinematographer of Christopher Nolan’s Inception and Dark Knight films and the director of the recent Johnny Depp film Transcendence—has long been in the vanguard of the anti-digital resistance. He argues that the technology tends to distract filmmakers from more important tasks, like working with actors and lighting the set. Whenever people tell him he should shoot in digital, Pfister says, “their agenda is to either try to sell more of this equipment or it’s to save money. The only agenda I ever have is putting a beautiful image on the screen. I want to be able to wing it a little bit. I want to be able to have what Conrad Hall [legendary cinematographer of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid] used to call a ‘happy accident,’ where you pan the camera through the sun and have somebody walk through in a silhouette, and still have something on the side of their face in the silhouette. The reality is that there is no digital capture medium where you can do that right now.” He’s referring to another version of the latitude problem, the long-standing tendency of DV to “clip,” or lose all image quality, in conditions of high or low light.

Arkenberg argues that the apparent ease of digital cinema leads to shortcuts, to what he calls a kind of laziness that ultimately means filmmakers and audiences alike settle for substandard artistry—for carelessly created images that simply aren’t as good as they could be. “People who work with film have a tight relationship to the medium, and a strong visual memory,” he says. “Whereas people who are used to digital formats have a poor sense of problem-solving. If they encounter a problem, the answer is always, ‘Let’s google it. We’ll fix it in post.’ Film is about an intense sense of the process. Digital is all about the result.”

A Problem in the Eye and Brain of a Camera

Cinematographer Gordon Arkenberg explains some of the downsides of digital recording. His comments have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

For a cinematographer, the most important thing is how does the color and tonality [brightness] of a real-world scene get through this process and out the other side. If I film a black bowl and white cup, will I get the black bowl and white cup I remember seeing with my eyes?

Let’s add a neutral-gray card to our cup and bowl. (For the sake of a good experiment, this neutral-gray card is brand new and tested to demonstrate it is entirely neutral in color and of the proper dye density to be truly middle-gray of my vision.) I light my scene with lights I have tested for color accuracy and, using my recently calibrated light meter, set the intensity of light [to a specific known level]. I set my lens [appropriately to the light level] and record the scene before me.

When I download the footage and use image-analysis tools, my neutral-gray card should be exactly 50% brightness. What I’ve found in doing this test with my students is that the [Arri] Alexa [a professional digital movie camera] comes out with pretty close to 50%. Very good! However, if I do this with the [other brands of high-end digital movie cameras], my neutral gray is pushed down to anywhere from 30-40%. Why? It makes no sense and it bewilders my students.

The explanation by [the other companies besides Arri] is that they are intentionally moving the tonality data down in brightness to preserve highlight values. Why is this important? Because digital sensors don’t render subtle highlight tones very well. My white porcelain cup is a challenge, so the data is transformed to help rescue it with the intention that I later use my computer to lift my tonality up again and can hopefully keep the subtle tones of the cup. Why don’t they just build a sensor and algorithm that just puts tones in the correct place to begin with? Arri has managed to do this; a major reason cinematographers have gravitated to that camera as the industry standard is because it readily produces an image they recognize as having been seen physically by their eyes.

The analog process is rooted in natural things we interact with directly and understand. With digital, the processes are man-made and confined in part by the thoughts of people.

Many cinematographers accept this manipulation of the data as helpful to their process since they can now adjust the tonality exactly the way they like it. I would argue that a black bowl should be a black bowl, and a white cup a white cup. Now I have a muddy white cup and a black bowl that has vanished into my black background. If I lift the tonality, I can indeed make all three objects look correct tonally, but the underexposure of the black bowl has added noise to its appearance that has negatively affected its image quality. So who decided it’s better to save the highlights at the expense of shadows? Is this an ad hoc solution? No one really has an answer given a good answer, but its a strange solution to those whose experience is with film.

The image-processing software is necessary to take the way a CCD and CMOS sensor record and render reality and turn it into an image with contrast and color that looks correct to our visual system. If you look at what a CCD & CMOS see, they render a very low-contrast, almost muddy, image with a greenish tint and muted colors.

In comparison, film inherently renders tones and colors in a way that looks correct (except obviously the negative records a negative image), because it was designed to fit quite naturally with how our visual system works. The digital engineers are forced to take a sensor that does not see like we do and use software to process the image so it does.

The analog process is rooted in natural things we interact with directly and understand: physical film transported through a camera, time and temperature of development, the light passing through a release print when projected in a theater. With digital, the processes are man-made and confined in part by the thoughts of people, and eventually the collective mind of the company making the product.

This is part two of a three-part series. Part one ran yesterday; part three, on digital cameras and film’s future, will run tomorrow.

Andrew O’Hehir is a senior writer at Salon.com.