Ten thousand years ago, a mother clutched her growing belly. A month earlier, the pregnancy had become difficult—something was wrong. The mother’s stress was the baby’s stress too, and the baby was due to be born in a few weeks.

The mother rested by the Neva River as it flowed down the mountains on its way to the sea. She lived in the Ligurian region of northwest Italy. People in her community went about their daily lives, gathering seeds and nuts, butchering mountain goats, and preparing meals. Some members tanned hides and prepared clothing, adding shell beads and pendants for decoration, some that had been passed down for generations.

Time went by and the day finally arrived. The woman gave birth to a baby girl, who was welcomed by the group with open arms. Things might have seemed fine at first, the baby crying, suckling, being passed around the group for love and comfort, but soon it would have been clear that the baby’s health was declining. Less than two months after birth, the young girl was gone.

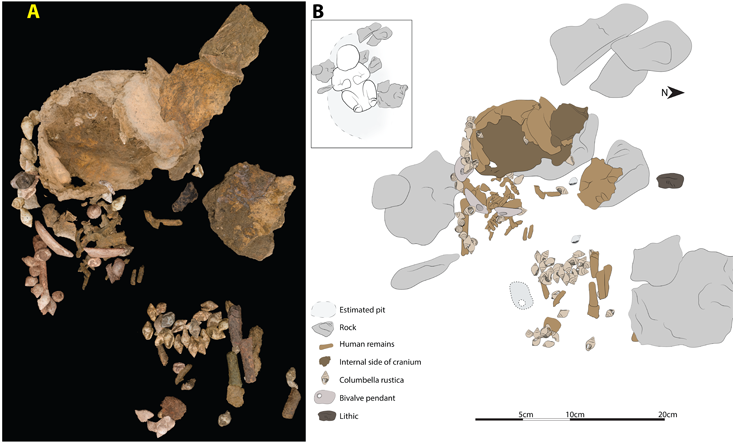

The girl’s mother and father, accompanied by their community, took her tiny body to a marble cave, just upslope from the river. Inside, the cave was beautiful. It ascended to a high point in the center, the walls draped by flowstone ribbons. A small pit was dug in the middle. The baby was wrapped in a garment decorated with over 60 pierced shell beads and three pendants. The pendants looked huge next to the tiny infant, but she was worth it. She had been a part of their group. The cave echoed with sounds of grief as the small body was returned to the earth. Along with her shells and pendants, she was removed from the life of the living and encapsulated in time.

The mother’s hand slid along the cave wall as she steadied herself to leave, her fingerprints marking this place with her love and her grief. The father’s tears dotted the ground. An aunt and uncle stayed back as other community members left, wanting one last moment. Their hands dug at the dirt covering the infant as they each made a small pit near the burial for their last gifts: the talon of an eagle owl, and another pendant.

This is what my scientific colleagues and I imagine unfolded at what is today known as the Arma Veirana cave. We began excavating at Arma Veirana in 2015. Our goal was to uncover archaeological material from Neandertals, and we did just that—the first two excavation seasons exposed stratigraphic layers that contained not only tools often associated with Neandertals in Europe (Mousterian tools) but also the remains of ancient meals that left behind cut-marked bones of wild boars, elk, and bits of charred fat.

We continued work at Arma Veirana in 2017, but that season was different. For one thing, I was pregnant, just beginning my second trimester, and having lost a prior pregnancy in a complicated miscarriage six months earlier.

Rather than starting the day on an arduous hike to the cave with the excavation team and hiking back to the lab in the village of Erli in the afternoon, as I had done in past seasons, I spent most days in the lab watching artifacts come out of the sieves, studying, and curating each found piece with students. Each night, as equipment was being put away, I was able to see what had been excavated and mapped in 3-D space, and members of the excavation team could see artifacts they had excavated, washed, and laid out in the lab. As we worked through July, 2017, everything was progressing as planned.

A main goal for the season was to better understand the stratigraphy of the cave as it related to the more than 50,000-year-old Mousterian artifacts we had recovered, and to expose potential Upper Paleolithic deposits that might be the source of artifacts we had found eroding down the cave floor, which slopes north toward the entrance. Our team expanded excavation units from the front toward the back of the cave. Sediments have eroded out of the front of the cave, so that older sediments are exposed nearer to the surface in the front, but younger sediments are still preserved in the back. As excavations expanded southward toward the back of the cave, we were moving forward in time.

In the lab, with one week left in the 2017 field season, I began to find pierced shell beads in the sieves. I called up to the cave with a warning, “We are getting close to something.”

On a hot, humid late afternoon, as I sat analyzing bone fragments and my colleague Fabio Negrino, an archaeologist from the University of Genoa, analyzed stone tools, the cell phone rang. “We are uncovering a burial.” Fabio and I rushed to the site. When we arrived, Geneviève Pothier-Bouchard, an anthropologist from the University of Montreal had exposed parts of an infant cranial vault and articulated lines of pierced shell beads.

The cliché that you always make the biggest finds on the last day was true. We were out of time. This was scheduled to be the last day of the excavation. Students had flights home, grant money had run out, and the excavation leaders had classes to teach. There was no way to excavate the cranium quickly without breaking it. Work was going to take weeks longer. We made the decision to cover the remains in a protective layer of sand, netting, and plastic to protect everything underneath until we could come back the following season. We walked away worrying and hoping everything would be OK. As we left, we were comforted by the knowledge that people from the nearby villages of Cerisola and Erli would keep watch over the site throughout the year.

In 2018, we returned. This time, Caley Orr, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and my husband, and I came as a family with our 6-month-old daughter, and her grandmother Deb Hulting. Over the course of five weeks, the remains of the buried baby were revealed by the steady hand of Pothier-Bouchard and Simon Paquin, also from the University of Montreal.

As we had done since the beginning of the excavation in 2015, photogrammetric images linked to 3-D coordinate data in the cave were taken by Dominique Meyer and Danylo Drohobytsky (then students at the University of California, San Diego), allowing for the team to recreate the excavation in a virtual environment. Sediment from the burial pit was placed in bags and carried in full to the lab, where I sieved the sediment through a 1 mm sieve. I recovered several of the infant’s baby teeth, stained brown over time, along with the tiny remains of hand and finger bones. Though I assume my emotions over the death of Neve are not as strong as the grief her group must have felt, I cried and grieved over Neve’s remains, especially as I sat recovering the tiny tubes of her hand bones.

By the end of the season, we had recovered all that remained of the infant of Arma Veirana. In a series of analyses, coordinated with multiple institutions and numerous experts, we learned details about this brief life.

Radiocarbon dating determined that the child lived 10,000 years ago. DNA and amelogenin protein analysis revealed that the infant was a female belonging to a lineage of European women known as the U5b2b haplogroup. Detailed virtual histology of the infant’s teeth showed that she died 40 to 50 days after birth, and that she experienced stress while in the womb, likely due to stress her mother experienced, perhaps from starvation, sickness, or injury, that briefly halted the growth of her teeth 47 days and 28 days before she was born. Carbon and nitrogen analyses of the teeth helped us see that the baby’s mother had been nourishing the infant in her womb on a diet composed of food from the land, not the sea. An analysis of the ornaments adorning the infant funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council demonstrated not only the time and care invested in each piece, but also that many of the ornaments exhibited would have taken longer to accumulate than she had lived and must have been passed down to her from group members only to be returned to the earth with her. Our team nicknamed the Arma Veirana baby “Neve,” which (in a funny twist) comes from Caley’s misspelling of the river valley where the site is located. But “neve” means “snow” in Italian, a beautiful word, and the name stuck.

As it turns out, Neve is the most ancient burial of a baby girl currently documented in the European archaeological record. In a paper published in Scientific Reports, we conclude that the burial of such a young female with abundant ornamentation reflects a degree of egalitarian treatment of individuals in life and death regardless of age or sex. The tremendous number of pierced shell beads and pendants found with Neve show very young females were afforded personhood in this Mesolithic society, despite the fact such young infants were unable to contribute materially to essential tasks. This is not always the case, especially in societies with high rates of infant mortality. Along with the burial of a similarly aged female from Upward Sun River in Alaska, the funerary treatment of Neve suggests that the recognition of infant females as full persons has deep origins in a common ancestral culture shared by peoples who migrated into Europe and those who migrated to North America. This recognition may have arisen in parallel in populations across the planet. Either way, the terminal Pleistocene and earliest Holocene shows definitive evidence for the recognition of young girls as members of human society.

In a strange way (a sort of ripple in time) it seems that Neve and my daughter were born together. The discovery of this infant at the time my child was developing in my womb, and the full excavation of Neve after the birth of my daughter are certainly intimately linked for me. The story of Neve offers many lessons.

There is pride and awe in the story of Neve’s mom, apparently struggling, as indicated by the stress lines in Neve’s teeth, and yet she carried on as generations of women have done, giving birth, and bearing loss. This is a connection that hits especially hard for me having experienced my own miscarriage mere months before Neve was found. The power and endurance of the mother should not be overlooked.

The story of Neve’s group carefully burying an infant girl and investing handmade heirlooms with her body, removing those goods from the living is a profound human story. To me, the story took on added significance because Neve was discovered on the heels of the 2017 Global Women’s March. It was a moment when equitable treatment for females seemed to have been illusory. It made me wonder: Are our modern attitudes toward women a continuation of long held ancestral behaviors? Or are the inequities we experience today a deviation from our ancient past? Is humanity defined by “othering” and demeaning some and elevating others, or is the creation of highly unequal societies a contradiction and betrayal of our humanity?

I hope the world into which Caley and I have brought our daughter will achieve higher standards of treatment and equality for women of all ages, cultures, and avocations around the world than it does now.

Jamie Hodgkins is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado, Denver. Her research is focused on the origins, evolution, and ecology of modern humans and Neanderthals. Much of this work has focused on reconstructing ecology and behavior of these peoples by studying their patterns of hunting and butchery as well as analyzing the mobility of their prey species through isotopic analysis. She is a project director for excavations at the late Pleistocene and early Holocene site of Arma Veirana in northwestern Italy. Her fieldwork has also included projects in North America, France, Spain, Bulgaria, Morocco, and South Africa.

The excavation team: Caley Orr (Paleoanthropologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine), Fabio Negrino (Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Genova, Italy), Claudine Gravel Miguel (Paleolithic archaeologist at Arizona State University), Julien Riel-Salvatore (Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Montreal), Marco Peresani (Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Ferrara), Stefano Benazzi (Paleoanthropologist at the University of Bologna, Italy), David Strait (Paleoanthropologist at Washington University), Christopher Miller (Geoarchaeologist at University of Tübingen).

An earlier version of this article appeared in Simple Beginnings: Exploring Human Origins, a blog site hosted by the Evolutionary Morphology Lab at Washington University in St. Louis.

Lead image: A digitally reconstructed image of the Arma Veirana cave with the burial seen just below the surface. Bones in the the top right corner are from Neve’s hands. Credit: Dominique Meyer, Danylo Drohobytsky, Falko Kuester, the Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative (CHEI) team, and the Qualcomm Institute and Jacobs School of Engineering at the University of California, San Diego.