An insistent pattern has quietly taken hold in my household. I will order some consumer product online. The product will arrive. I will open the package, extract the thing from its protective wrappings, and retrieve the instruction manual. I will examine the product briefly, then begin to read the instruction manual. And then I will go to YouTube.

There, I will find, almost invariably, that someone has already done the thing that I am hoping to do. They will have documented the process with varying degrees of professionalism ranging from chirpy, well-captioned professional productions to people in their poorly-lit bedrooms.

Most recently, it was a hitch-mounted bicycle rack for my car giving me trouble. The written instructions were telegraphic, the drawings may well have been ancient cuneiform. I found my salvation on YouTube, and the rack was road-ready in minutes. When I later thanked a friend who had recommended the product, I confessed I had gotten a video assist on the install. “The guy with the Subaru?” he asked. “In his driveway?” Our path to enlightenment had apparently crossed, along with some 57,000 other viewers.1

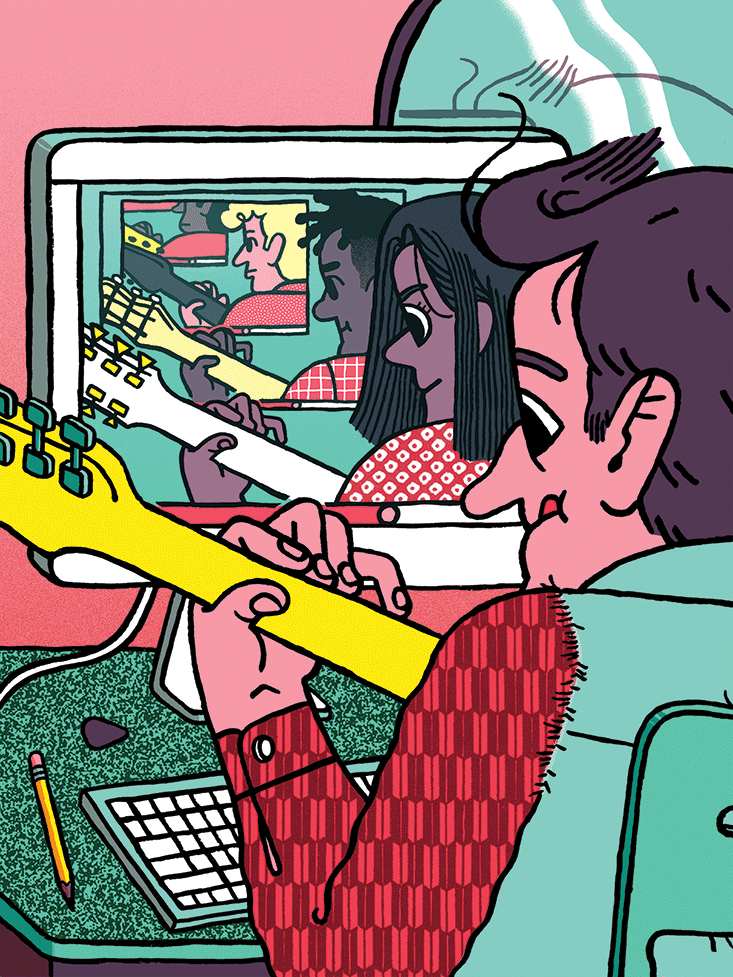

It is not just product assembly. My YouTube search history is filled with moments of fleeting pedagogy: How to best “pop up” on a surfboard, how to play Dinosaur Jr.’s “Get Me” on guitar, how to set up a private server for my daughter’s Minecraft (Minecraft tutorials alone must number in the hundreds of thousands). When a plumber came by to unclog our toilet, he tenderly told me after I could have done the same thing with an auger from the hardware store—and saved $100. And so I immediately purchased the device. But how to use it properly? To YouTube I went, suddenly realizing I should have looked there first. I was steered to a video of a man patiently demonstrating auger technique on a sample jam. This task, he noted, was a plumber’s “cash cow.” He joked about being forgiven, if any plumbers happened to be watching, for “giving away the secrets.” But he need not have worried: YouTube is rife with auger demonstrations from plumbers themselves.

Last year, it was estimated that YouTube was home to more than 135 million how-to videos.2 In a 2008 survey, “instructional videos” were ranked to be the site’s third most popular content category—albeit a “distant third” behind “performance and exhibition” and “activism and outreach.”3 More recent data suggest that distance may have closed: In 2015, Google noted that “how to” searches on YouTube were increasing 70 percent annually.4 The genre is by now so mature that it makes for easy satire.

What are people looking to do? The most popular searches, by one analysis, range from the achingly prosaic to the exceedingly specific—from “how to kiss” to “how to make a rainbow-loom starburst bracelet.” You can learn how to boil water, field strip an AR-15 rifle, or fly a 747. But stories abound of people—usually kids—achieving impressive proficiency in everything from opera singing to dubstep dancing by simply copying what they have seen in YouTube videos.5 YouTube pedagogy has swept through—and virtually helped create—fields like competitive cubing (Rubik’s), where solve times have plummeted, aided largely by the transmission of techniques via YouTube.6

There is, to an extent unparalleled in history, the promise that anyone, anywhere in the world, without cost or travel or the embarrassment of public failure, can learn just about anything. Some take it too far: When a Las Vegas man was arrested last year for performing illegal surgical operations—he does not have a medical degree—he noted that while he had long read medical textbooks, his primary educational source was YouTube. “You don’t watch one, you watch like 20 or 25 [videos] like I do,” he said. “Pretty close to anything you want to learn you can learn it off YouTube for free.”7

I am not about to attempt open-heart surgery. But as I racked up time looking for people to show me how to do things, I wondered: Why did this seem to be such an effective way to learn, and how could I do it better?

We humans are not alone in being able to learn through video observation. A 2014 study showed that when a group of marmosets were presented with an experimental “fruit” apparatus, most of those that watched a video of marmosets successfully opening it were able to replicate the task. They had, in effect, watched a “how to” video.8 Of the 12 marmosets who managed to open the box, just one figured it out sans video (in the human world, he might be the one making YouTube videos).

Robots can do it too. The problem, though, is that robots do not learn very effectively from watching one demonstration. Ozan Şener, a researcher at Cornell University, notes that even in object recognition tasks in computer vision, researchers routinely train robots using millions of photos of objects. “There is no way you can collect a million demonstrations of anything,” he says.

YouTube is catnip for our social brains.

So Şener and his fellow AI researchers at Cornell wondered if there was a way to solve this problem. As Şener put it: “What kind of data exists which is already collected, which is scaleable, which spans lots of activities and lots of environments?” The answer, of course, was YouTube. A search for an activity like “How to tie a bow tie,” Şener noted, generates upward of 250,000 hits on YouTube. Using the 100 most popular videos for a given popular task, the team set the robots loose in an unsupervised learning task, leaving it to them to try to figure out what was significant. Even left to their own devices, the robots were able to write text instructions for the tasks they’d observed.

With robots, as with humans, it may be easier to show them what to do than to tell them. But humans have robots beat in the sheer efficiency with which we can learn. We don’t need 100 videos to learn to tie a bow tie. This, says Luc Proteau, head of the Department of Kinesiology at the University of Montreal, is a defining feature of humans.

“We are built to observe,” as Proteau tells me. There is, in the brain, a host of regions that come together under a name that seems to describe YouTube itself, called the action-observation network. “If you’re looking at someone performing a task,” Proteau says, “you’re in fact activating a bunch of neurons that will be required when you perform the task. That’s why it’s so effective to do observation.”

We are, in effect, simulating doing the task ourselves, warming up the same neurons that will be used when we actually give it a go. “It’s thought that the observation network developed as a means of understanding what the meaning is of actions performed by others,” Proteau says. “If we see someone making a fist, you will be able to understand, if I was doing that, what would be the purpose—to hit someone.”

This ability to learn socially, through mere observation, is most pronounced in humans. In experiments, human children have been shown to “over-imitate” the problem-solving actions of a demonstrator, even when superfluous steps are included (chimps, by contrast, tend to ignore these).9 Susan Blackmore, author of The Meme Machine, puts it this way: “Humans are fundamentally unique not because they are especially clever, not just because they have big brains or language, but because they are capable of extensive and generalised imitation.” In some sense, YouTube is catnip for our social brains. We can watch each other all day, every day, and in many cases it doesn’t matter much that there’s not a living creature involved. According to Proteau’s research, learning efficiency is unaffected, at least for simple motor skills, by whether the model being imitated is live or presented on video.10

As good a fit as YouTube is for our social brains, there are ways we can learn from videos even better.

The first has to do with intention. “You need to want to learn,” Proteau says. “If you do not want to learn, then observation is just like watching a lot of basketball on the tube. That will not make you a great free throw shooter.” Indeed, as Emily Cross, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Bangor University told me, there is evidence—based on studies of people trying to learn to dance or tie knots (two subjects well covered by YouTube videos)—that the action-observation network is “more strongly engaged when you’re watching to learn, as opposed to just passively spectating.” In one study, participants in an fMRI scanner asked to watch a task being performed with the goal of learning how to do it showed greater brain activity in the parietofrontal mirror system, cerebellum and hippocampus than those simply being asked to watch it. And one region, the pre-SMA (for “supplementary motor area”), a region thought to be linked with the “internal generation of complex movements,” was activated only in the learning condition—as if, knowing they were going to have to execute the task themselves, participants began internally rehearsing it.11

Subjects seemed to learn tasks more effectively when they were shown videos of both experts performing the task effortlessly and the error-filled efforts of novices.

It also helps to arrange for the kind of feedback that makes a real classroom work so well. If you were trying to learn one of Beyonce’s dance routines, for example, Cross suggests using a mirror, “to see if you’re getting it right.” When trying to learn something in which we do not have direct visual access to how well we are doing—like a tennis serve or a golf swing—learning by YouTube may be less effective. You might be able to learn the chords of your favorite song through simple mirroring, but at least one guitarist notes some problems in the idea of “learning by copying from YouTube.” While self-taught guitarists can often “spit back” notes, robot-like, he suggests that only a teacher in the room can help develop more intangible (but no less important) factors like “tone” and “groove.”

On the other hand, Justin Sandercoe, a longtime guitar player and teacher in the United Kingdom, who has famously built up a massive library of online lessons (even before YouTube), thinks people can largely tell if they are getting better or not at playing a piece of music by comparing their performance to the online version they are trying to emulate. Whatever might be lacking in terms of a person not being in the room with the student, he suggests, is made up for by the sheer convenience of online learning. “If you learn something one on one, and forget about it later when you’re at home, you can’t really rewind it.” On YouTube, a student can endlessly rewind—and the teacher won’t get frustrated.

The final piece of advice is to look at both experts and amateurs. Work by Proteau and others has shown that subjects seemed to learn sample tasks more effectively when they were shown videos of both experts performing the task effortlessly, and the error-filled efforts of novices (as opposed to simply watching experts or novices alone).12 It may be, Proteau suggests, that in the “mixed” model, we learn what to strive for as well as what to avoid.13 Watching Roger Federer is not enough—we need to see the average duffer flailing about on the court. As Daniel Lametti and Kate Watkins, professors at the University of Oxford, note, “observing someone failing to learn—such as someone who is already an expert (e.g. Federer)—provides no benefit to observers when they actually go to learn the task.”14

In other words, seeing learning happening actually helps us learn. Although, admittedly, sometimes we do not want to learn plumbing—we just want to fix the damned toilet.

Tom Vanderbilt writes on design, technology, science, and culture, among other subjects.

References

1. Mitchell, D. 1Up USA Quik-Rack Platform Bike Rac. YouTube (2011). https://go.nautil.us/BikeRack

2. Jones, J. Micro-moments: I want to do moments. DigitalNext.co.uk (2016).

3. Landry, B. & Guzdial, M. Art or circus? Characterizing user-created video on YouTube. Georgia Institute of Technology (2008).

4. Mogensen, D. I want-to-do moments: From home to beauty. Think with Google (2015).

5. Nash, M. & Endara, M. Five people who used the internet as their teacher, the results are amazing. Fusion.net (2016).

6. Strachen, M. Rubik’s cube champion on whether puzzles and intelligence are linked. The Huffington Post (2015).

7. KSNV. Full Interview: Fake doctor, Rick Van Thiel, says he learned surgical procedures on YouTube. News3lv.com (2015).

8. Gunhold, T., Whiten, A., & Bugnyar, T. Video demonstrations seed alternative problem-solving techniques in wild common marmosets. Biology Letters 10 (2014).

9. Whiten, A., McGuigan, N., Marshall-Pescini, S., & Hopper, L.M. Emulation, imitation, over-imitation and the scope of culture for child and chimpanzee. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 364, 2417-1428 (2009).

10. Rohbanfard, H. & Proteau, L. Live vs. video presentation techniques in the observational learning of motor skills. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2, 27-32 (2013).

11. Picard, N. & Strick, P. Activation of the supplementary motor area (SMA) during performance of visually guided movements. Cerebral Cortex 13, 977-986 (2003).

12. Rohbanfard, H. & Proteau, L. Learning through observation: A combination of expert and novice models favor learning. Experimental Brain Research 215, 183-197 (2011).

13. Andrieux, M. & Proteau, L. Observational learning: Tell beginners what they are about to watch and they will learn better. Frontiers in Psychology 7, 1-32 (2016).

14. Lametti, D.R. & Watkins, K.E. Cognitive neuroscience: The neural basis of motor learning by observing. Current Biology 26, R288-R290 (2016).