Last fall, I went to an egg freezing cocktail hour. The downstairs bar of the glossy SoHo hotel was thronged with women in heels and sleek business attire. Club music thumped, cameras flashed, and I narrowly missed being hit by a videographer angling a tripod over the crowd. The evening was hosted by Eggbanxx, a startup that sells financing for egg freezing, framed as fertility insurance for the forward-thinking urban professional woman.

At the bar, where they were serving up free “Banxxtini” cocktails, I spoke with a 27-year-old who was “95 percent sure” she would freeze her eggs and a 36-year-old data scientist who claimed to be “skeptical.” Together, we filed into a screening room adjoining the bar, where three New York-area endocrinologists lectured us on a new technique that, they claimed, could freeze our reproductive chances in time. Female fertility declines sharply at 37, due to a decline in the quantity and quality of eggs. But when women use fresh eggs from a young donor in an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle—a process in which fresh eggs are harvested from the donor, fertilized, and transferred to the uterus—live birth rates rise across ages to 56 percent.1 Now, thanks to a new freezing technology, women could become their own future egg donors, rather than relying on the fresh eggs of another, younger donor. “It’s good to be empowered as a woman,” beamed Janelle Luk, a doctor at Neway Fertility.

Nicole Noyes of the NYU Fertility Center, lean and intense, spoke energetically about egg freezing, a field in which she was an early leader. She began with a reassuring screenshot of her recent study finding no higher risk of birth defects among 900 children born from frozen eggs.2 Her clinic’s results seemed incredible: If a woman freezes her eggs at 35, Noyes told us, and uses them at, say, 43, she has a 50 percent chance at a live birth from one IVF cycle. Compare that to her unaided chances of conception (using IVF or naturally) at age 43: 5 percent each cycle. If she freezes her eggs later, at 38, her success rate for one IVF cycle dips to 37 percent. According to Noyes, success is determined by the age at which you froze the eggs. “31 is as long as I’d wait,” she told one questioner in a swarm of audience members, many still clutching purple cartons of popcorn, after the presentation. I had lost sight of the 27-year-old, but I spotted the data scientist hurrying up an aisle to sign up.

I found myself considering egg freezing again, based on a biomedical marketing event dressed up as a girls’ night out in Sex and the City.

On the subway ride home, as I pawed through my gift bag containing, among other goodies, a single miniature Lindt white-chocolate egg, I felt anxious, convinced that if I didn’t freeze my eggs, I’d be sorry when I was 40. Either I’d gotten a dose of reproductive straight-talk or I’d fallen for a pitch to which—naively—I’d thought myself immune.

Because I actually froze my eggs once before, seven years ago. When I was a 28-year-old graduate student, I learned I had endometriosis, which is often linked with infertility. As I had already lost one ovary, I met with a fertility preservation specialist, who advised me to freeze my eggs. I got 22 eggs, which are still stored in a cryobank, at a cost of $700 a year. At the time, the treatment was experimental: The odds of those eggs resulting in pregnancy are slim, about 4 percent each. But still, I have a stake in those eggs—I realized it back at the cocktail hour, when I learned how poorly their odds compare to eggs frozen with today’s improved technology. Now, at 36, I can still have children and am still not ready to do so, because I don’t want to raise kids alone. And so, to my surprise, I found myself considering egg freezing again, based on a biomedical marketing event dressed up as a girls’ night out in Sex and the City.

I decided to look into the science of egg freezing myself, hoping that what I found could determine my choice. But it didn’t. Not only were there competing statistics about the odds of conception with frozen eggs, there were also the odds of finding the right partner in time, and a calculation of our precise degree of regret if I make the wrong choice now. Elective egg freezing, I discovered, demands a decision, but does not admit any clear answers.

“I think this egg freezing business puts women in a hard position,” I told one of the doctors I interviewed. He had no idea what I meant. “Any option is better than no option,” he told me. By which he meant, any increased chance of getting pregnant later is better than no increased chance. But at this particular cultural moment, and for this generation of women, he was missing the point.

Sometime after the Eggbanxx event, I woke to another article in The New York Times by a woman who regretted not having children in time: “Freeze your eggs now!” she exhorts a 37-year-old protégée, and, by extension, the reader. By all accounts, more and more healthy women are choosing to freeze their eggs. While there are no official statistics, doctors from two major fertility centers say the number of patients seeking elective egg freezing has doubled annually since 2010, and the use of assisted reproductive technologies, chiefly IVF, has doubled in the past decade.

Egg freezing and IVF are arguably part of a vast demographic shift—a global trend toward delayed childbirth among the affluent.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American women 35 years and older had first-children nine times as often in 2012 as they did 40 years earlier. This trend has made for big business: In The Baby Business, former Harvard economist and president of Barnard College Debora Spar estimates the United States fertility industry was worth about $3 billion in 2004, of which IVF and fertility drugs accounted for $2.4 billion.4 Writing in 2006, Spar predicted one obvious way for the market to grow was by extending services from the infertile, about 15 percent of American women, to the perfectly fertile—women eager to “hedge” their fertility bets by freezing their eggs.

Just last October, NBC reported that Apple and Facebook would pay $20,000 for healthy female employees to freeze their eggs electively, for the purpose of delaying motherhood, prompting massive online debate. Supporters backed it as a bold new initiative to empower career-minded women, while critics derided it as a cynical ploy to get women to work longer hours courtesy of an expensive, risky (they claimed) procedure. With this move, the tech companies effectively endorsed the new fertility technology, adding to a widespread conviction that freezing your eggs as a childless, 30-something woman who can afford the out-of-pocket price tag ($10,000-$15,000 just for the drugs and egg retrieval process) is the obvious thing to do.

For many, egg freezing can seem to be just what the doctor ordered. But what is lost in the debate is that both the effectiveness and the risks of egg freezing are far from certain. The science of egg freezing is just too new.

This generation of women is buying into a grand experiment.

Just 2,000 babies have been born from cryogenically frozen eggs in the world—and only 20, for instance, in all of Great Britain.5 Early data suggests that egg freezing is a woman’s best bet for having her own genetic children in her 40s, but framing egg freezing as reliable fertility insurance encourages women to rely too heavily on a technology that is still being refined in many of the clinics where it is being sold.

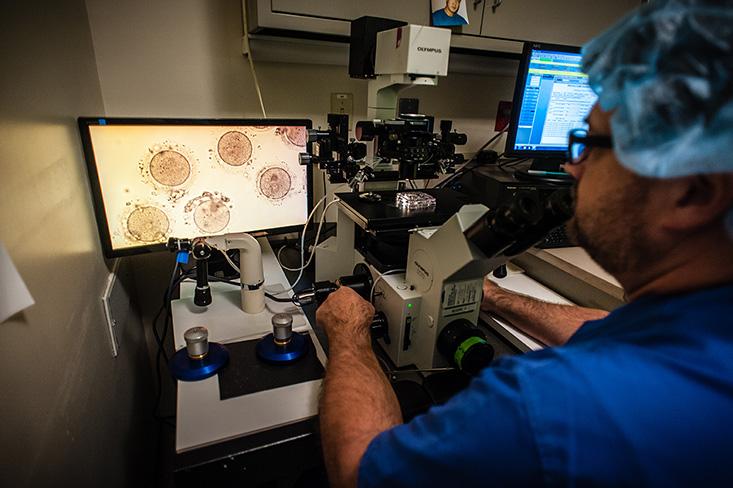

For decades, the technological barrier to freezing eggs was the difficulty of thawing them. “I had just hundreds of women clamoring after me for egg freezing technology,” said Michael Tucker, a leading embryologist at Shady Grove Fertility and Donor EggBank USA. He was describing the flood of phone calls he received after the publication of a 1997 article about the old egg-freezing technology. At the time, embryologists were using the “slow-freeze method”—the one I’d used—which he and the rest of his field generally found unreliable. The egg, as the largest human cell, is highly liquid; as it freezes, it forms ice crystals, which crack upon thawing.

In the late 1990s, scientists started developing the new vitrification process, in which the egg is dehydrated, treated with anti-freeze, and flash-frozen at a lower temperature, which prevents ice crystals from forming and increases chances of a successful thaw. Over the past 10 years, vitrification has largely supplanted slow-freezing. Using vitrification, Tucker was “much more supremely confident to say, yes, we can provide consistently good fertility outcomes.”

That Shady Grove Fertility has seen 200 babies born from frozen eggs supports this claim, but Tucker—like other doctors I interviewed—insists that egg-freezing success varies widely by clinic. For one thing, vitrification is finicky. Tucker told me it requires deft coordination and visual judgment, adding, “We have 26 embryologists and I would trust vitrification to six of them. And warming to four.” Tucker, who has led training programs across the country, says he believes that it will be at least four years until clinics across the board can offer similarly consistent results. “That smacks of self-promotion,” he acknowledged, but Tucker is hardly alone in this cautious assessment.

This is the Catch-22 of elective egg freezing: Its effectiveness will remain unknown until enough frontrunners join the experiment.

The American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the self-regulatory organization for U.S. fertility clinics, is not ready to endorse the commercialization of egg freezing. In 2012, the ASRM lifted egg freezing’s “experimental” label, thanks to the success and apparent safety of the vitrification process. For a woman, the main risk of egg freezing is ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), caused by fertility drugs, which can cause everything from bloat to, in severe cases, urine stoppage and bleeding.6 The ASRM has claimed that, without embryo transfer, the risk of OHSS is low, and that 0.4 percent to 2 percent of women taking fertility drugs experience severe OHSS.7, 8 It is more difficult to resolve the question of risks to children born from frozen eggs, as this technology is too new for long-term studies, but the ASRM cited good results from recent studies on infants, including Noyes’.

Still, while the ASRM approved egg freezing for medical purposes—largely for young women with cancer about to undergo sterilizing chemotherapy—the organization cautioned against its “widespread elective use to delay child bearing.” After reviewing nearly 1,000 papers, the ASRM could find only four randomized control trials that compared fresh and frozen eggs, mostly from clinics with high pregnancy rates, using eggs from young donors. Not a wide pool of clinics, or 30-something patients. Therefore, the authors concluded, a woman should not put off having children in favor of freezing her eggs, because “there are no data to support the safety, efficacy, ethics, emotional risks, and cost-effectiveness” of using egg freezing for this purpose.9

This is the Catch-22 of elective egg freezing: Its actual effectiveness will remain unknown until enough frontrunners join the experiment.

Of course, the ASRM’s stance is far too cautious for some women eager to hedge their fertility bets, and for some ASRM-member fertility clinics, many of which have actively endorsed elective egg freezing for years. In 2010, 143 fertility clinics reported that they offered egg freezing, with 63 percent of the clinics offering elective egg freezing.10 The technology is very promising, according to Pasquale Patrizio, the director of the Yale Fertility Center, which offers elective egg freezing (they do not partner with Eggbanxx). Patrizio repeated the same formulation I’d heard at the cocktail hour: If a woman freezes an egg, she freezes her chances of getting pregnant with that egg. “The data is starting to appear now,” he said. He’d just seen some reassuring statistics presented at the annual ASRM convention in Hawaii, by Noyes.

In the weeks after the egg freezing cocktail hour, it was Noyes’ ringing endorsement that lingered in my mind—and her data, which shows the powerful potential of elective egg freezing. When we connected by phone, Noyes told me that in Hawaii she’d presented statistics similar to those at the cocktail hour: Using frozen eggs, the NYU Fertility Center had achieved 62 births and ongoing pregnancies—a 44 percent success rate by cycle, which is impressive, considering that about a third of IVF cycles produce live births.11 Thirty-one of those 62 births and pregnancies were with women using their own eggs. Those who had frozen their eggs between ages 25-34 had a 42 percent chance of a delivery or ongoing pregnancy per cycle; using eggs frozen between 35-40, a 37 percent chance per cycle; from 41-42, a 33 percent chance per cycle (though this oldest group was represented by a small sample size). Noyes would later tell me that she has revised her estimates to be slightly more conservative. To be on the safe side, Noyes recommends that a woman should freeze 20 eggs for one pregnancy, and, in her late 30s, should expect three freezing cycles to produce that many eggs—and to thaw and implant them. This, of course, translates to a huge investment of time and effort for women hoping to get pregnant. And, of course, money: At the NYU Fertility Center, one cycle of egg freezing, two years of storage, and three attempts to thaw and use those eggs currently costs, by my calculations, $39,410 to $46,560.

Tucker gave me unpublished data similar to Noyes’: Out of 98 pregnancy and thaw cycles in which women used their own frozen eggs at Shady Grove Fertility, 36 produced ongoing pregnancies and live births, with results similarly varying by age. This means that, on average, women had a 36.7 percent chance of having an ongoing pregnancy or live birth by IVF cycle using frozen eggs, comparable to her chances at NYU. These are the kind of optimistic statistics that writer Sarah Elizabeth Richards, who paid nearly $50,000 to freeze 70 eggs between the ages of 36 to 38, quoted in her The Wall Street Journal essay, “Why I Froze my Eggs (And You Should Too).”

But the largest data set available, which looks at outcomes for individuals from a wide range of clinics, suggests that NYU Fertility Center and Shady Grove Fertility’s success rates are exceptional. A 2013 meta-analysis in Fertility and Sterility, which considers pregnancy outcomes from 2,265 thaw and implantation cycles, performed for 1,805 patients, shows rates roughly half as successful as those described by Noyes.12 For patients who transferred three embryos, success rates were, at 35 years old, 19.3 percent; at 38, 16.5 percent; and at 40, 14.8 percent per cycle. Egg freezing critics use this study to claim that egg freezing fails outrageously often.

The more I knew about egg freezing, the less I felt empowered—largely because of the impossible psychological stance I was being asked to take.

To get a clearer picture of these competing statistics, I called Kutluk Oktay, a reproductive endocrinologist at the New York Medical College best known for his revolutionary work on ovarian tissue freezing, a fertility preservation technique mainly intended for cancer patients. He was also, full disclosure, my fertility preservation specialist. Oktay seemed a bit surprised to hear the 2013 meta-analysis was being used to argue against elective egg freezing. He sees it as a slightly conservative assessment, as it draws from data from infertile patients, who likely have poorer outcomes than healthy women freezing electively. Still, he frames it as the best predictive data available to patients, disagreeing that any clinic can provide a baseline success rate by age, as Noyes did at the Eggbanxx event, without documenting hundreds of pregnancies first.

“There is no study that looks at elective freezing and if doing that helps women preserve fertility,” Oktay said. This, he told me—as did Patrizio—is because very few women, healthy or otherwise, who have frozen their eggs have actually come back to thaw their eggs. So while the data looks promising, doctors can’t make any guarantees—yet.

The data is further complicated by the fact that there is currently no way to compare clinics’ programs. That’s because although the CDC and the ASRM collect IVF data, they do not yet track egg freezing. Both warn potential patients not to use their data to compare clinics, as some clinics turn older, infertile patients away, or end unpromising cycles. So when choosing a clinic, a woman is limited to word-of-mouth—and gossip. “You have to go to a third-party source,” Gina Bartasi, the founder and CEO of Fertility Authority, EggBanxx’s parent organization, told me, comparing the process to choosing a hotel, complete with review. While it’s easy to see how Eggbanxx can help a woman compare costs, which can vary widely between clinics (NYU charges about $2,400 more per freezing cycle than neighboring Weill Cornell), it’s a bit too early for anyone to predict a clinic’s success rates.

The important thing, said Patrizio, is for patients to understand that egg freezing offers not fertility insurance, but “hope.” Oktay tells patients, “An insurance policy guarantees to pay if your house burns down,” so “egg freezing is not an insurance policy. It’s a lottery.” He tells patients not to delay childbirth on account of their frozen eggs. “Freeze your eggs, but pretend that you did not freeze your eggs.”

In vitro fertilization is the new normal in my part of Brooklyn. With enough time, money, and effort, the thinking goes, anyone can become a parent. You just have to give it your all! The Eggbanxx event framed elective egg freezing as part of this narrative, empowering women to seize control of their reproductive fates. Richards told me women she knows who have frozen their eggs speak of its psychological benefits, in part because it takes the pressure off dating: “If you think they’re going to work, you’re living your life with more confidence.” Egg freezing seems to offer women the chance to decide what kind of life they want to live, freed from their biological clocks. It seems to give women a choice.

But this version of empowerment really points to a deeper constraint. The fact is that women mainly freeze their eggs because they haven’t found a partner yet, as Emma Rosenblum found while researching her 2014 Bloomberg Businessweek cover story, “Later, Baby? Will Egg Freezing Free Your Career?”13 Similarly, Noyes’ team, surveying 183 egg-freezing patients on why they were delaying childbirth, found that just 24 percent cited professional reasons, while 88 percent cited lack of a partner.14 In spite of this newfound choice, women are still bound by deeply held cultural expectations about motherhood, starting with the idea that childless women suffer endless regret. The opportunity to freeze their eggs can deepen the power of this expectation.

In researching egg freezing, I have been struck not just by the technology’s potential, but also by the impossible psychological stance I have been asked to assume: That is, to have enough trust in this new technology to freeze my eggs, but not enough trust to alter my life choices—to delay having a child, possibly on my own, or seriously prepare myself for other options, like adopting children or not raising children, at all. I am not sure how to do all that.

I am sure that I don’t want to buy into the unfortunate societal norms reified by egg freezing: That women with money can reproduce how and when they want to, while poor people can’t; that we should have a genetic connection with our children; that even though a third of couples who struggle to conceive do so based on male infertility (which also increases as men age) infertility is pretty much a woman’s fault, and therefore a woman’s problem to solve. “There’s this sense that it’s all on us,” one friend told me, adding that, for her, egg freezing feels “lonely and stigmatizing and hopeless.”

I am also sure that I don’t want to surrender a relative fortune and a month of my beautiful, ordinary life for bloat-inducing hormone injections, pelvic ultrasounds, weight gain, and worry about the future.

Then again, if I don’t freeze my eggs now, I will have ignored all fair warnings from Noyes, various New York Times writers, and dog park acquaintances—not to mention statistical accounts of female fertility’s decline. I will have rejected the best technological solution on the market. And so, if I can’t have a baby one day, I will probably blame myself. That is why, for me, egg freezing is not fertility insurance: It’s the perfect regret machine.

Abby Rabinowitz has written for The New York Times and teaches writing at Columbia University.

References

1. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Committee Opinion. Female Age-Related Fertility Decline (2014).

2. Noyes, N., Porcu, E., & Borini, A. Over 900 oocyte cryopreservation babies born with no apparent increase in congenital anomalies. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 18, 796-776 (2009).

3. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief. First Births to Older Women Continue to Rise. (2014).

4. Spar, D. The Baby Business: How Money, Science, and Politics Drive the Commerce of Conception. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA (2006).

5. Gafson, I. The facts don’t lie: We haven’t cracked egg freezing. Not even close. The Telegraph (2014).

6. Johnston, J. & Zoll, M. Is Freezing Your Eggs Dangerous? A Primer. New Republic (2014).

7. Gera, P.S., Tatpati, L.L., Allemand, M.C., Wentworth, M.A., & Coddington, C.C. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: steps to maximize success and minimize effect for assisted reproductive outcome. Fertility and Sterility 94, 173-178 (2010).

8. American Society for Reproductive Medicine: Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (2015).

9. The Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertility and Sterility 99, 37-43 (2013).

10. Rudick, B., Opper, N., Paulson, R., Bendikson, K., & Chung, K. The status of oocyte cryopreservation in the United States. Fertility and Sterility 94, 2642-2646 (2010).

11. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2012 Assisted Reproductive Technology: Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report (2012).

12. Cil, A., Bang, H., & Otkay, K. Age-specific probability of live birth with oocyte cryopreservation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility 100, 492-499 (2013).

13. Rosenblum, E. The Real Reason Women Freeze Their Eggs Isn’t Career Growth. Bloomberg Business (2014).

14. Hodes-Wertz, B., Druckenmiller, S., Smith, M., & Noyes, N. What do reproductive-age women who undergo oocyte cryopreservation think about the process as a means to preserve fertility? Fertility and Sterility 100, 1343-1349 (2013).